|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

Philosophical Thought

Reference:

Kotliar E.R., Puntus E.Y.

The Cultural Code "Bestiary" in the Jewish Pictorial Semiosis

// Philosophical Thought.

2023. ¹ 4.

P. 19-50.

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8728.2023.4.39946 EDN: BYPLNV URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=39946

The Cultural Code "Bestiary" in the Jewish Pictorial Semiosis

Kotliar Elena Romanovna

PhD in Art History

Associate Professor, Department of Visual and Decorative Art, Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University named after Fevzi Yakubov

295015, Russia, Republic of Crimea, Simferopol, lane. Educational, 8, room 337

|

allenkott@mail.ru

|

|

|

Other publications by this author

|

|

|

Puntus Ekaterina Yur'evna

Senior Lecturer, Department of Design, State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education "Crimean University of Culture, Art and Tourism"

295034, Russia, Republic of Crimea, Simferopol, Kievskaya str., 39

|

allenkott@mail.ru

|

|

|

|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8728.2023.4.39946

EDN: BYPLNV

Received:

11-03-2023

Published:

30-03-2023

Abstract:

The subject of the study is the cultural code "Bestiary", which combines symbolic images of animals and chimeras in the Jewish pictorial semiosis. The object of the study is traditional symbolism in Jewish pictorial practice. The article uses the methods of semiotic analysis in deciphering the meanings of the elements of the traditional pictorial Jewish semiosis, the method of analyzing previous studies, the method of synthesis in substantiating sets of signs. In their work, the authors consider the following aspects of the topic: the main codes of the Jewish pictorial semiosis are highlighted, their morphology, interrelationships, key meanings and the main code are substantiated. The Bestiary code, its features, etymology and reading are considered in detail. The main conclusions of the study are: 1. Based on the study of Jewish traditional culture, five main codes of pictorial semiosis in Judaism were identified, uniting a group of symbols: skewomorphic (subject), phytomorphic (plant), zoomorphic (animal), numeric. The primary source of all codes and the unifying code is the Sefer code (Book). The interactions between the codes are revealed, the key meanings are the symbolism of Creation, Paradise, Torah persons and Messianic aspirations. The semantic center of the codes – the Torah and Aron Hakodesh, as a repository of the Torah, is revealed. 2. The Bestiary code considered in detail represents the symbolism of traditional images of animals and chimeras, which is connected with the prohibition in Judaism on the image of a person. Images of representatives of the world of animals, birds, fish, as well as mythical creatures in the Jewish reading convey the meanings of human virtues and negative qualities, and also indicate Messianic hopes laid down in the Torah and especially in the Midrash Talmud.The scientific novelty of the study consists in the fact that for the first time a culturological analysis was carried out and the interrelationships of cultural codes in the Jewish pictorial semiosis were structured, with an emphasis on the Bestiary code.

Keywords:

Cultural code, Judaism, Bestiary, Pictorial semiosis, Zoomorphic symbols, Torah, Aron Hakodesh, Talmud, Midrash, Mythology

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

The famous Russian sociologist and cultural critic Nikolai Yakovlevich Danilevsky (1822-1885) in his significant work "Russia and Europe" (1869) identified a number of "cultural and historical types", the most important category of which is religion. "Religion is the moral basis of any activity" [1, p. 157], "Religion is the predominant interest for the people at all times of their life" [1, p. 225], "Religion was the most essential, dominant (almost exclusively) content of ancient (...) life, and (...) in it it is the prevailing spiritual interest of ordinary (...) people" [1, p. 577]. Social identity before the globalization of the twentieth century was based on belonging to a certain religion. This thesis was confirmed by other ethnographers, in particular, Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov. Structuring of the Jewish cultural code is impossible without referring to the fundamentals of Jewish religious beliefs. The term Jew has a number of meanings. The most general of them is the definition of a social group whose religion is based on the Torah (the Mosaic Pentateuch), but without extensions (unlike representatives of other Abrahamic religions – Christians and Muslims, in whose sacred books – the Bible and the Koran – the Torah is supplemented by subsequent sections). Thus, this definition classifies groups not by ethnic (anthropological), but by confessional. According to this classification, Jews include: - Ashkenazi Jews;- Sephardic Jews; -Jews-mizrahim – common name of Eastern Jews – (Bukhara Jews, Georgian Jews, mountain Jews, Persian Jews, Ethiopian Jews);

- karaites; - krymchaks; - Russian Judaizers; - subbotniks. Another meaning, narrower, consists in defining the term Judaism as both a denomination and a Jewish ethnic group, in this case Judaism is a national religion [2].

Our research does not concern the issues of anthropology and ethnogenesis, we consider symbolism in visual practice exclusively on examples of preserved artistic artifacts, most of which belong to the second half of the XIX – first third of the XX century. The nations professing Judaism include: Ashkenazi Jews are an ethnic group professing Talmudic Judaism (whose creed is based on the Tanakh (consisting of the Torah (the Pentateuch of Moses), the books of the Prophets and Hagiographers) and the Talmud (the book of interpretations of the Tanakh by the sages). The term Ashkenaz comes from the Hebrew name of medieval Germany, which has been found in Jewish sources since the tenth century. Ashkenazim were called Eastern European Jews-immigrants from Germany who settled as a result of migrations in Poland and the Baltic States. The spoken language of the Ashkenazim was Yiddish, a German dialect, and the language of worship was Hebrew (Hebrew). Ashkenazim are followers of the Palestinian tradition in liturgics. Another Jewish subcultural region was Sefarad, which included the Iberian peninsula and the southern part of France. Natives of this region are called Sephardim. Sephardim are followers of the Babylonian liturgical practice, their literary language for a long time was Arabic, and their spoken language was Ladino. The subcultural type of Italian Jewry combines features of the Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions. The Jews who migrated to the Crimea with its annexation to the Russian Empire, overwhelmingly belonged to the Ashkenazim, who subsequently created their own traditional community on the territory of the peninsula [3, p. 52]. Karaites – ("readers") (self–designation – "karai" or "karai" in the singular, "Karaim, karaylar" - in the plural), the people of Crimea, professing non-Talmudic Judaism (self-designation Karaism), the essence of which is following the Torah and not accepting any of its interpretations (including the Talmud). Despite the fact that the Karaite language, like Crimean Tatar, belongs to the Kypchak group of Turkic languages, the writing of the Karaites and Krymchaks is based on the Hebrew alphabet [4]. The Krymchaks (self–designation "krymchakh" in the singular, "krymchakhlar" in the plural) are the people of Crimea, professing Talmudic Judaism of the Sephardic sense with admixtures of local traditions. The ethnonym "Krymchak" first appeared in official documents of the Russian Empire in 1844, to distinguish this Jewish group from Ashkenazi Jews who migrated to Crimea from Russia and Poland since the end of the XIX century. At least from the XVI – XVII century. The Crimean Tatars switched to the ethnolect of the Crimean Tatar language (Kypchak group) [5]. Folk decorative and applied art clearly demonstrates the synthesis of cultures, the common ethno-cultural field. Such interpenetration is a natural consequence of the compact residence of peoples on a single territory, which is clearly confirmed by the presence of a continuum of ethno-cultural codes of decorative and applied art.

The relevant direction in this context is the comparative semantic-symbolic, stylistic and typological study of the works of Jewish folk art, as well as the analysis of stable symbols based on a single source – the Torah. Pictorial semiosis is a subsection of semiotics, a science that analyzes sign systems and their connections. Semiotics, as a philosophical trend, emerged at the end of the XIX century, simultaneously developing in two directions: semiology and pragmatics. The foundations of semiological research are contained in the works of the Swiss philosopher, linguist and semiotic Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913), who dealt with the semiotics of a linguistic sign and derived the concept of a "two-sided sign" consisting of a signifier (word) and a signified (form value). The connection of the signifier and the signified, according to Saussure, is conditional: the meanings of the sign may differ for different groups of people [12]. The founder of pragmatics was the American philosopher, logician and mathematician Charles Sanders Pierce (1839-1914), who studied signs from the point of view of logic. Pierce believed that a sign can be called anything that means an object. Signs that outwardly do not resemble the signified object, Pierce called symbols [11]. The Belgian Association of Semiotic authors Mu (transcription of the Greek letter ?) (founded in 1967), has developed a semiotic structure of three levels: iconic, symbolic, index. Italian cultural theorist, philosopher, specialist in semiotics and medieval aesthetics, writer Umberto Eco (1932 – 2016) developed the concept of a sign and sets of signs to codes meaning not a specific, but a general object. Eco called a message conveyed by a sign or a series of signs a text. The theory of cultural text became one of the main postulates put forward by the Soviet and Russian semiotic and cultural critic Yuri Mikhailovich Lotman (1922-1993). He is the author of the theory of the "semiosphere" of culture created on the basis of the works of French structuralists. Later, the Russian cultural critic Andrei Yakovlevich Flier (born 1950) included the definition of "Cultural text" in the category of cultural concepts. Traditional visual elements of any ethnic decor are divided into two types: 1. Elements of the ornament; 2. Separate stable images and/or plots.According to the definition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, ornament (ornamentum – "decoration" (Lat.) accentuates or reveals the architectonics of the object, the decor of which it is. The elements of the ornament are stylized or abstract motifs. The visual symbolism of ornamental elements originally had an applied, magical meaning. The second most important function of the ornament is aesthetic. Both of these functions continued to exist in synthesis, which makes it possible, knowing the cultural codes of certain ethnic groups, to determine the values of individual elements of ornaments and their aggregates. Vladimir Vasilyevich Stasov (1824-1906) in his fundamental work "Russian Folk Ornament" emphasized the idea of the archaism and symbolism of ethnic ornament: "The ornament of all new peoples in general comes from the depths of antiquity, and the peoples of the ancient world have never concluded a single idle line: every dash here has its own meaning, is a word, phrase, the expression of well-known concepts, representations. The rows of ornaments are a coherent speech, a consistent melody that has its own main reason and is not intended for the eyes alone, as well as for the mind and feelings" [13]. In addition to the ornament, that is, compositions of elements repeated with different frequency, there were separate stable images or plots in folk art. The etymology of these plots goes back to magical or religious meanings. All visual elements in folk art are divided into three categories: physiomorphic (including images of objects), abstract (geometric) and epigraphic (textual). In turn, physiomorphic images are divided into five subsections: zoomorphic – images of real and mythical animals, anthropomorphic – images of a person, phytomorphic – images of plants, skewomorphic – images of objects and astral – images of the sun and stars.

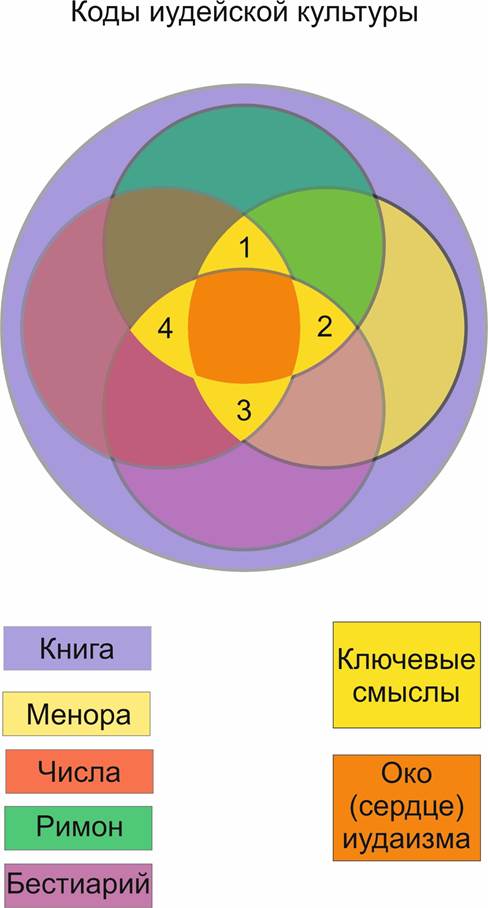

Interest in the artistic side of the Jewish tradition arose at the end of the XIX century, when, due to globalization and the desire of young people to cities, towns began to fall into desolation. The ethnographic expeditions undertaken in order to preserve the cultural heritage, led by ethnographers S. Ansky (Shlomo Rappoport), S. Taranushenko, P. Zholtovsky, laid the foundation not only for ethnographic collections of household and ritual Jewish objects, but also for the study of fine Jewish semiosis. In particular, the subject of this study were drawings made during the expeditions by S. Yudovin, P. Zholtovsky, etc., on which the artists captured the subjects of reliefs on tombstones and murals in synagogues. These stories became the basis of articles on Jewish art by Rachel Bernstein-Vishnitzer, Zinaida Yargina. Later, researchers of Ashkenazi Jewish towns, professors of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Boris Khaimovich, Veniamin Lukin, Vladimir Levin, Nelly Portnova, Professor of St. Petersburg State University Valery Aronovich Dymshits, and others wrote about traditional images of animals and their symbols. However, all these authors considered bestial plots in a general historical and cultural context, without distinguishing them into a separate branch of research, and did not systematize the range of traditional images and their interrelations, considering them from a historical and art criticism point of view, but not from a generalized philosophical, cultural point of view.In the Jewish pictorial tradition, the presence of different types of images was distributed heterogeneously. In Ashkenazi folk art, the main iconic elements were images of symbolic animals, fish, birds, as well as chimeras. A large number of images also included a human figure or part of it. Plant and astral elements were present to a lesser extent. In Sephardic folk art, geometric and plant elements formed the main repertoire of images. To clarify the determination of the Jewish cultural code of folk art, it is necessary to determine what its function is decisive for this study. Under the cultural code in modern cultural studies, it is customary to understand the key to the concept of a certain picture of the world. The concept of "code" comes from a technical environment, its meaning consists in deciphering languages, however, the meaning of the term has been expanded to a philosophical level. There are several definitions of the cultural code: 1. Cultural code as a sign structure (in pictorial semiotics – a certain circle of images); 2. Cultural code as a system of ordering (use) of symbols (in our case – in pictorial symbols, for example, in ornamentation – canon: type of construction, composition, order of precedence, values, etc.) 3. Cultural code as a kind of accidental or natural correspondence of the signifier and the signified (in visual embodiment, it can be applied to archaic symbols present simultaneously in the cultures of many peoples, for example: sun, tree, wave) The functions of the cultural code are: a) deciphering the meaning of individual phenomena (texts, signs, symbols) – in the absence of a code, the cultural text remains closed (in the case of visual semiotics, for example, ornament, in this case it is perceived only from the point of view of stylistics, compositional features, color, etc., without deciphering the meanings of its elements and their totality) b) the relationship between the signifier (sign) and the signified (object, phenomenon, meaning); F. Saussure explained the term cultural code with the help of linguistics, language construction [11]. However , the subject of our article is more closely related to the proposed U. Eco is a semiotic concept of the S-code (semiotic code), according to which the image is constructed according to strictly defined canons, rules of combinatorics. Also, according to him, the same statement (image) can be understood differently (from different angles) by representatives of different groups. So, in the case of an ornamental motif (for example, a tree), its meaning can be perceived differently by representatives of different ethnic groups. Exploring an extensive layer of artifacts, we consider it expedient to present the codes of the Jewish pictorial semiosis in the form of a diagram of the type of Euler circles (Fig. 1). The diagram of the Swiss, Prussian and Russian mechanic and mathematician Leonard Euler (1707-1783) – "Euler circles" allows you to visually identify the relationships between subsets by superimposing planes on each other.

Figure 1 We have identified five codes with the help of which the main meanings of any traditional images concerning Jewish culture are revealed, with the following names [8]: 1. Sefer Code (Book) 2. Menorah Code 3. Number Code

4. The Rimon Code5. Bestiary Code The Sefer code is the main "Book" (Hebrew), which includes all other codes, is depicted in the diagram in the form of a large lilac circle, inside which the four remaining circles (codes) are placed. The Sefer code includes all the key verbal sources that are the basis of Judaism. The main difference between Judaism and other ancient beliefs was monotheism. According to the Jews, God, through the prophet Moses, gave them a set of laws (Covenant) in the form of tablets, obliging to strictly adhere to the commandments and not to honor other gods. Subsequently, this covenant was formed into a number of sacred books, including the Torah (the Pentateuch of Moses), Neviim (the Books of the Prophets) and Ktuvim (the Scriptures), which are the basis of Judaism as a creed. In recognition of the extremely important role of this code in the life of the Jewish people, it is sometimes referred to simply by the word Sefer – Book, in many parts, Sfarim – Books. The Commandments and Laws of Moses constitute "the semantic core of Judaism ... the basis of the Jewish religion, as well as the basis of Jewish ethics and law"; this is "the central document of Judaism" [6, p. 5]. The canonical version of the written Torah was designed by the scribes Ezra and Nehemiah. In 457 BC, the scribe priest Ezra brought to Jerusalem from Babylon a version of the Torah used by the Babylonian exiles. There were other versions of Scripture in Jerusalem at that time, so there was a need to streamline the canonical version of the Torah. Ezra and Nehemiah have done this work for 13 years with the support of dignitaries and elders (the autonomous Administration of Judea). After the completion of the written canon of the Law, it became necessary to popularize, introduce and explain it. Thus, in Judaism, the second part of the Law was formed – the so-called oral, consisting of interpretations of the written Law. The active process of formation of the Oral Law – the Oral Torah began in the IV century BC. The oral Torah contained eschatological ideas that were not illuminated or poorly illuminated in the written Torah: about the immortality of souls, the afterlife, the Last Judgment – the posthumous retribution for earthly sins (violations of the commandments), as well as many prescriptions concerning religious andhousehold rituals [6, pp. 3-27]. There is a postulate that the Oral Torah was given to Moses simultaneously with the written law, but it was written down by the sages later. The written formalization of the oral Law – the Talmud – dates back to the II–V centuries. According to the figurative characterization of the Israeli rabbi, Torah translator, founder of the Institute for the Study of Judaism Adin Steinsaltz (1937-2020), "If the Bible [means the Torah – author's note. articles] are the cornerstone of Judaism, then the Talmud is its central pillar supporting the entire spiritual and philosophical code ... (It) is a collection of oral laws developed by generations of sages in Palestine and Babylonia up to the beginning of the Middle Ages." The Oral Law, united by the common name Talmud ("teaching" – Hebrew), consists of two components: the Mishnah and the Gemara. The Mishnah, in turn, includes Halacha, Midrash and Haggadah. The Mishnah in its present state was edited in the third century . By Yehuda Ha-Nasi. The first printed edition of the Mishnah appeared around 1485 . Halakha is a set of laws, prescriptions (both in written and oral Torah). The Code of the basic laws of Halakha, used up to the present time inclusive – Shulkhan Aruch (lit. "set table" – Hebrew) It was structured and recorded by the Spanish rabbi, a major authority and expert on the Jewish canon, Yosef ben Ephraim Karo (1488-1575). Midrash is a genre of homiletic and exegetical literature consisting of sermons by sages, parables that explain the essence of a particular law or phenomenon described in the Torah. A ggada is a creatively reworked parable or a real story from the life of the sages, presented with artistic fiction, demonstrating in the form of an allegory the effect of a prescription or punishment for its non–fulfillment. The Aggada is also essentially a midrash. The earliest Midrash that has come down to us is the Easter Haggadah, which contains a description of the Passover holiday and prescriptions for the traditions of its veneration. The name Gemara was originally positioned as a later synonym of the Talmud, that is, interpretations of the Torah and Mishnah, which arose in the era of persecution of the Talmud as an anti-Christian work. In a number of sources, Gemara is called the Talmud as a whole, as well as its individual chapters. However, in fact, the Gemara is a separate and later source containing additions and interpretations of the sages to the already existing chapters of the Mishnah.

Kabbalah belongs to one of the most famous and widespread (up to the present time inclusive) mystical and esoteric currents of Judaism, in which the ontological essence of God and his role are considered, as well as attempts are made to interpret certain hidden meanings of the Torah. The current arose in the XII century, but its main spread was in the XVI century. Initially, the term Kabbalah was used for all books that were not included in the Pentateuch, and later for the entire Oral Law, but since the 12th century the sages began to emphasize the esoteric component of their teachings. During the heyday of Kabbalistic teaching (1270-1320), the main book of its postulates was written – Sefer ha-Zohar, or, abbreviated, Zohar ("book of radiance" – Hebrew). The book contains mystical interpretations of various Torah plots. In fact, the Zohar is a book of Midrash eschatological content, written on behalf of travelers to Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel), the main theme of which is the knowledge of God, and at the same time, the recognition of his unknowable. Yellow Circle – Menorah code; The name of the Menorah (as the main and most ancient Jewish symbol) is given to a code that deciphers a group of skewomorphic images of Jewish cult attributes. The initial description of cult objects is contained in the Torah in the form of instructions given by God to create and equip the Tabernacle of the Covenant (to store the tablets of the Torah), and subsequently the First and Second Temples [Exodus (Shmot) 25-27]. The main shrine, which has a special place in Judaism, is the Torah [8]. The reading of the Torah is the basis of the liturgy on Saturdays and holidays. The Torah is a scroll written on parchment by a specially trained master, a copyist soifer – from the word Sefer – "book" (Hebrew); every four parchment pages are sewn together with special threads, forming ieria – sections, connected, in turn, into a scroll. The ends of the scroll are attached to round wooden rollers etz Chaim – "Tree of Life" (Hebrew), with handles on both sides; wooden discs are put on between the handles and the roller, supporting the scroll, while it is in an upright position [9]. Among the Sephardim, the Torah was traditionally placed in a case made of wood or metal, among the Ashkenazim – in an embroidered cloth cover, most often velvet. In the Middle Ages, the tradition of lavish decoration of the Torah case was established – it is crowned with rich in shape and ornamentation finials – Keter Torah crowns - "Crown of the Torah" (Hebrew), or metal finials in the form of garnets – rimmonym. A special plate with a hammered ornament is suspended on a chain, often inlaid with semi–precious stones - torashild or tas [3]. It is forbidden to touch the parchment with your hands, so when reading the scroll, use a special pointer yad – "hand" (Hebrew), in the form of reproducing a human hand with an outstretched index finger. A ritual object close in meaning and design to the Torah scroll is Megila Esther – "the scroll of Esther" (Hebrew) – one of the Old Testament books traditionally read during the Purim holiday. According to the text of Scripture, the covenant on the manufacture of the menorah was given to Moses by the Almighty on Mount Sinai simultaneously with the commandments [Exodus (Shmot) 25:9]. Literally translated, the menorah is a "lamp" (Hebrew), however, the concept is traditionally applied to the synagogue seven–candle, all branches of which are deployed in one plane. With all the variety of menorahs, regardless of the territory and period of their creation, they all have a resemblance to a tree, which is directly indicated in the above text of Scripture. Three-four-five-candle lamps, made for both temple and household needs, are also close to the menorah. A special kind is the so–called Hanukkah – nine-barrel lamps used on strictly defined days of one of the most important holidays of the Jewish calendar - Hanukkah. The items of primary importance in the Jewish liturgical practice include such elements of the male ritual costume as: - talit (Hebrew) or tales (Yiddish) is a prayer shoulder covering of white rectangular shape, with several woven black or black and blue stripes. In the middle of the longitudinal part of the talit, an atara is most often sewn – "crown, crown" (Hebrew) – a rectangular piece of fabric to distinguish the upper outer and lower inner parts. The talit is put on during the recitation of a certain Shaharit prayer on the head, throwing all four ends of it over the left shoulder, forming an Ismail wrap, after which it falls on the shoulders.; - tsitsit (the Crimeans chichit, the Karaites chichit or arba kenafot – "four corners" (Hebrew)) – brushes or a bundle of threads sewn to the four ends of men's clothing, according to the prescription contained in the Torah [Numbers (Bemidbar) 15:38-41]. In each bundle there should be a dyed blue thread, when looking at which everyone should remember the commandments. The tzitzit should be visible from under the clothes. In some Hasidic communities, a talit katan, worn under clothing, is practiced – a small talit (Hebrew) (in comparison with talit gadol – a large talit (Hebrew)), on which there is necessarily a tzitzit. Among Karaites, a chichit (arba kenafot) is a scarf with embroidered patterned ends, with white, blue and green tassels along its edges. Karaite chichit was not only worn on the shoulders, but also hung on the walls of kenas, understanding the commandment to "look at chichit" literally;

- kippah (yarmulke) – literally "covering, dome" – a round knitted or sewn with wedges cap, worn by Jews and Crimeans on the crown, under the main headdress (for example, a Hasidic hat). Crimean Karaites wore a pointed kalpak hat instead of a kippah during prayer (the daily headdress of both Karaites and Krymchaks was a black lamb cap of the Crimean); Karaites also did not wear long curls at the temples, the commandment of which is contained in the Tadmud. - tfilin (Hebrew)or phylacteries (Greek) – two wooden or leather boxes with leather laces, with fragments of texts from the Torah inside, worn by a man during certain prayers on his forehead and on his hand, respectively, in fulfillment of the biblical injunction [Deuteronomy (Dvarim) 6:6-8; cf. Exodus (Shmot) 13:9, 16; Deuteronomy (Dvarim) 11:18]. Karaites, unlike Jews and Crimeans, do not wear tefillin. One of the obligatory items used in the synagogue ceremony of separating the Sabbath from the rest of the week is bsamim, or godes (hadas) – "myrtle" (Hebrew) – a special vessel for incense Bsamim, as a rule, are metal vessels of various shapes, with holes for burning incense [8]. Special ritual objects also include: - special decorated circumcision knife; - Elijah's chair – carved wooden chair for moel – performing the rite of circumcision; - a bowl with inscriptions for the circumcision ceremony; - Chupa – decorated wedding canopy for the wedding ceremony; - ktubba (shetar Karaites) – richly decorated marriage contract; - silver ring-a ring worn by the groom on the bride's index finger with the inscription Mazal Tov; Special purpose among the attributes of prayer houses are vessels – tzedakah – mugs for donations, as well as jugs for ritual washing of hands. Green circle – code Rimon – "garnet" (Hebrew); The name Rimon (as one of the Jewish symbols of unity in faith) was chosen for the code combining phytomorphic images. It is worth noting that the image of the pomegranate as a symbol of unity is also used in other cultures and ethnic groups, however, it has a different meaning, for example, among the Turks – the unity and multiplicity of family, clan. In the Torah there are descriptions and mentions of various plants: pomegranate, grape, fig, palm, cedar, aloe, almond, olive, thorn, oak, wheat, etc. The key phytomorphic symbol is two Paradise trees: the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. In general, plant symbolism, represented in the form of images of flowering trees with fruits and birds sitting on them, or their individual branches, or vases with flowers and fruits, personifies the Garden of Eden, crying for paradise lost and hope for the coming of the Messiah and return to paradise. Plants also serve as a symbol of the fertility of the promised land (the ambassadors who returned from the land of Canaan with grapes, figs and pomegranates [Numbers (Bemidbar) 13:17-24], the dove who returned to Noah in the ark with an olive branch [Genesis (Breishit) 8:8-11]) Red Circle – Number Code; The Number code combines numerical symbols, and is also named identically to one of the books of the Torah. According to the Jewish worldview, there are no minor details in the Torah, each aspect of it carries both direct and allegorical meaning. The main method of Jewish dialectics, pilpul, is based on the search for hidden meanings and the explanation of contradictions in Scripture. One of the aspects of Kabbalah is the translation of texts (words) The Torah into numerical values (due to the literal spelling of numbers in Hebrew), and the subsequent decoding of the values of these numbers. Symbolic numbers in Judaism are, for example: 1 – the unity of God; 2 – two guardians of the Gates of Paradise and the gates of the Temple; 7 – the number of days of creation, days of the week, branches of the Menorah, 12 – the number of tribes of Israel (descendants of Jacob (Israel), each of which inherits a certain land [Genesis (Breishit) 49:1 – 27]); the number of stones of the altar of Moses [Genesis (Breishit) 24:4]; 40 days and nights of Moses' stay on Mount Sinai with God [Exodus (Shmot) 24:16-18]; 40 years of wandering in the desert [Numbers (Bemidbar) 33:38-39]; 613 – the total number the commandments given to Moses by God, etc. The purple circle is a Bestiary code, which is the subject of our article, we will consider this aspect in detail. The Bestiary code combines zoomorphic, as well as zooanthropomorphic images: animals, as well as birds, fish (including mythological, chimerical). Zooanthropomorphism is a distinctive eschatological category of this circle of images in Judaism, since absolutely all animals or chimeras are presented for the purpose of humanizing the image, including visually (animals are often depicted in human poses – for example, bears walking on two paws, lions, animals with human eyes, muzzles resembling a face, etc.).

There are two reasons for such pictorial metamorphoses. The first, practical, is due to the fact that the images were geographically located in synagogues in Western and Eastern Europe, extremely remote from the habitat of animals mentioned in the Bible, that is, simply, folk artists have never seen a live lion or even a bear. For this reason, the models for images that were repeatedly redrawn and modified were medieval miniatures once imported to Europe, which themselves tended to a grotesque, chimerical vision. It can be assumed, for example, that the Messianic plot about the battle of a lion and a unicorn, often found in Jewish pictorial practice, was a directly seen, and not a fictional struggle between a lion and a rhinoceros (unicorn), which is quite real, for example, for Jews who were in Egyptian captivity. However, later the unicorn was depicted as a mythical horse with a horn on its forehead, which is understandable, since the horse was a familiar animal for European latitudes, while there was nowhere to see a rhinoceros. In general, the primitive folk style most often had exactly the real reasons for the absence of nature. Another aspect is precisely the deliberate humanization of animal images by artists. This, of course, is due to the strict prohibition on the image of a person, and the allegorical reading of animal images in the meaning of a person, that is, the transmission of Scriptural subjects through images of animals, not people. But the main reason why animals have a human look or image is the mysticism of Judaism, especially its Hasidic reading, where such images are found most often. The parables of the Talmud Midrash are often meaningful, allowing for many interpretations and meanings, and eschatological Messianic aspirations, especially intensified during difficult periods, encouraged folk artists to create mystical images. The Jewish bestiary carries an allegorical meaning, each of the images is the personification of God, man or his individual qualities. Images of symbolic animals mentioned in Scripture are most often found in three types of compositions. The first, most common, is the canonical composition of Aron Hakodesh in the form of a portal, where the niche for storing the Torah is guarded by guards (lions or a lion and a unicorn), a lion or an eagle (or a double–headed eagle) crowns the top of the composition, and birds are depicted in the branches of the paradise tree above the portal. Such a composition is repeated with slight variations in book graphics, artistic metal, wood carving, embroidery, etc. The second type of compositions with a bestiary spread on them adorns Ashkenazi tombstones-matzevs, located in the towns – the line of Jewish settlement established by Catherine for the residence of Jews in the Russian Empire, as well as in Western and Eastern Europe. Their symbolism is different. A number of images directly indicate the names of the buried, for example, a bear (Ber in Yiddish) was depicted on the matzo of a man named Ber, a Lion (Arye) – on the grave of a man named Arye-Leib, etc. Zooanthropomorphic symbols on mats can also include the depicted parts of the human body in the meaning of the whole. Such a peculiar vision, a naive departure from violating the commandment not to depict a person, was not accepted in all Jewish communities, in particular, those who were geographically close to Islamic culture (Crimeans, Karaites, Spanish and Italian Sephardim) adhered to stricter enforcement of the ban. However, for Eastern European towns, especially for Hasidim, this reading was characteristic. Grave grave grave grave images of a hand with a jug (pointing to the grave of a girl), a hand with a broken branch or a flower in it (on the grave of a young man or girl) (Fig. 2), a hand with a writing pen (on the grave of Soifer, a copyist of the Torah), blessing hands of the high priest – Aaronides (on the grave belonging to the tribe Aaron), etc.

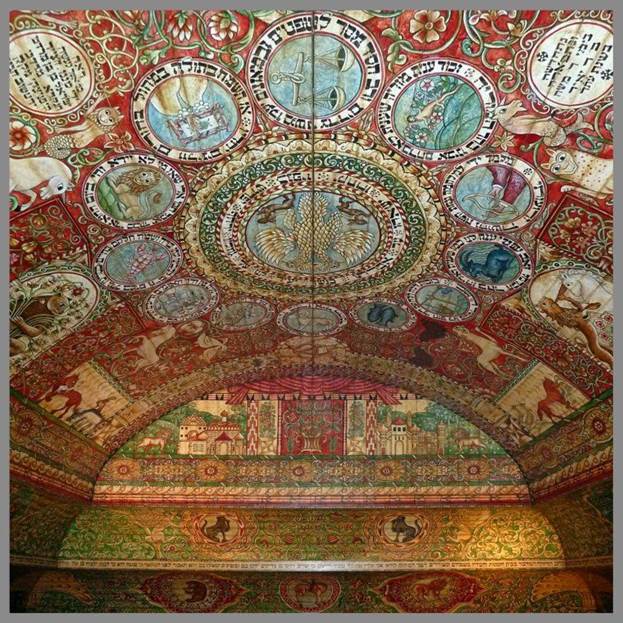

Figure 2. Image of a broken rose on the grave of a girl, Jewish cemetery in Siret, Romania. The third type of bestial images includes the Zodiac, borrowed by the Jews and interpreted as the personification of the twelve main holidays. In it, zoomorphic images are bizarrely side by side with anthropomorphic ones, and depicted in their own way and in a different order than in the classical zodiac circle, based on the same considerations of prohibition. So, for example, the Gemini sign was depicted in the form of two hands in a castle or simply located side by side, Sagittarius in the form of a hand with an arrow, etc. Consider the meaning of animal images that occur most frequently. Lev (Aryeh). Each of the twelve tribes of Israel has its own symbol, so the Lion symbolizes the royal tribe of Judah [Numbers (Bemidbar) 28:49]. The lion (as well as the wild bull (Shor), as well as the eagle) are images of the power of God, who brought the Jews out of Egyptian captivity [Numbers (Bemidbar) 23:22; 28:49] ( 3). It is for this reason that the figure or the head of a lion or an eagle often crowns the composition of the synagogue Aron-Hakodesh, as an image of God, who is above the whole universe. Images of lions are also often found in the image of formidable guards guarding the entrance to the Temple, the symbol of which is the niche for storing the Torah in Aron Hakodesh (Fig. 4). This is an indication of the representatives of the royal family of Yehuda, who keep the covenants.

Figure 3. A lion on a tombstone, Jewish cemetery, Siret, Romania. The eagle is a symbol of the Almighty, according to the Torah: "You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I carried you on eagle wings, and brought you to Me" [Exodus (Shmot) 19:4; Numbers (Bemidbar) 28:49; Deuteronomy (Dvarim) 32:11]. The image of an eagle crowns Aron Hakodesh and other traditional compositions, showing the supremacy of God over the world and people. The variant of the image of the double-headed eagle means a combination of mercy and justice of the Almighty (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. A double-headed eagle and two lions in the form of guards guarding the Torah. Synagogue in Bakshany, Romania.

The bull (Shor) also symbolizes the Almighty, who brought the Jews out of Egypt [Numbers (Bemidbar) 23:22] (Fig. 5). The bull is mentioned in the Torah as a sacrificial animal, as a symbol of hard agricultural labor, and as an image of strength and benefit. In the latter sense, the Bull represents the image of God as omnipotent, omnipotent (as well as the other two powerful images – a strong and formidable animal Lion, and a strong bird of prey – Eagle).

Figure 5. The image of a bull in the form of the zodiac sign Taurus. Synagogue in Chortkov, Podolia. The griffin is a chimerical animal, which is a synthesis of these two images (the body of a lion with the head and wings of an eagle) is also the personification of God, but in its Messianic meaning, the image of the parting of the soul with the body, according to Kabbalah. The griffin also symbolizes cherubim – beings of the higher otherworld, whose images are mentioned in the Torah as figurines decorating the Tabernacle of the Covenant and the Holy of Holies of the Temple [Exodus (Shmot) 25; Third Book of Kings 6:23-29] (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Image of griffins and a lion on a tombstone, Jewish cemetery in Siret, Romania. The unicorn (Tahash) is also a Messianic symbol, the personification of the battle of the righteous with evil in the days of the coming of the Messiah. According to one of the translations, the Tabernacle of the Covenant (a portable temple) was lined with Tahash skins [Exodus (Shmot) 25]. The unicorn is a mystical animal, the image of which is at the same time familiar to people, as it resembles a horse, but the horn on the forehead makes this image ephemeral, reminiscent of Messianic aspirations, miracles of God and hopes for his mercy. The already mentioned widespread plot about the battle of the lion and the unicorn preceding the coming of the Messiah has a philosophical meaning of confrontation of contradictions, binary opposition, during which the truth comes to light, therefore this plot is sometimes placed in the form of guards on the sides of the portal Aron Hakodesh, where the Torah containing true wisdom is kept. Also, the union of a Lion and a Unicorn in a single composition symbolizes the unification of Judea and Israel. The lion and the unicorn are often depicted on mats as a symbol of Messianic hope and the soul's transition to another world (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. The Battle of the Lion and the Unicorn. The image on the tombstone in Kuta, Podolia. Leviathan is a symbol of Messianic expectations in the parables of the Midrash. According to the myth, a number of animals that will come together in a deadly battle will be served at a feast upon the arrival of the Messiah. These include the bull Shore, Lion, Unicorn, Leviathan, Deer Zvi. The delicious meat of Leviathan, according to legend, will be a reward for the righteous. Leviathan is described in the Midrash as a sea monster, but in the images it has the appearance of a large fish resembling a pike (the use of which as a sample is obvious, since the pike is a river fish, familiar to the pale of settlement) (Fig. 8). The image of a fish also means fertility, a symbol of well-being, satiety, as well as, with their When placed in a circle, fish are a symbol of the cyclicity of time (Fig. 9). Sometimes three hares running in a circle are depicted in a similar meaning.

Figure 8. Leviathan on the tombstone. Jewish cemetery, Kuta, Podolia.

Figure 9. Three fish on a tombstone, Jewish cemetery, Siret, Romania. An elephant with a tower on its back is a symbol of a righteous man carrying the covenants of God, an allegory of the gravity of covenants and their fulfillment. The deer (Tzvi) is a symbol of beauty, purity, nobility, in the Mishnah it is mentioned as a symbol of the rapid fulfillment of the commandments. In the "Song of Songs", the deer represents the beloved, a variant of the Fallow Deer (Chamois) – the beloved (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Deer with a vine of grapes. The image symbolizes the messengers of the land of Canaan. Jewish cemetery in Kuta, Podolia. The stork in the images means a righteous man, pure as the white plumage of this bird. Bear (Ber) indicates the name Ber, also humanized bears (less often deer or other animals) (Fig. 10), walking on their hind legs and carrying a bunch of grapes, symbolize people who brought the fruits of grapes from the land of Canaan [Numbers (Bemidbar) 13:17-24] (Fig. 11). The plot is especially common on tombstones.

Figure 11. Bears carrying a bunch of grapes. Jewish cemetery, Satanov, Podolia. The dove (Dove) is a symbol of purity, righteousness, and good news. A dove brought an olive branch to Noah in the ark, testifying to the habitable earth after the flood [Genesis (Breishit) 8:11]

Figure 12. A dove on a tombstone, a Jewish cemetery in Siret, Romania. Scorpions, toads, venomous snakes, bats, locusts are mentioned (and depicted) as negative symbols [Deuteronomy (Dvarim) 9:15-16; Prophets (Nevi) 2:20]. In some cases, the animals mentioned in Scripture have a direct meaning (herds of goats, sheep, sacrificial lamb/kid). Zooanthropomorphic images can also include images of individual parts of the human body as an image of the whole, for example, the blessing hands of the high priest – Aaronides. Similarly, the signs of the Zodiac are depicted, which belong to a separate group of bestial symbols and mean in the Jewish reading the circle of the twelve main holidays, the twelve months, the 12 tribes of Israel. Zodiac signs in the design of synagogues were not displayed in their original order, but interpreted in accordance with the Jewish reading. Just as in the case of other images of people, the part in them means the whole. Thus, the Virgin is depicted as a hand with a jug, Twins in the form of two hands, etc. The images of animals as zodiac signs are also interpreted in the Jewish interpretation: the sign of Taurus – Bull – the Image of the Almighty, the sign of Leo – a similar meaning, Pisces – a symbol of fertility, the cyclicity of time, etc.

Figure 13. Aaronides' blessing hands on the tombstone, Jewish cemetery in Siret, Romania.

Figure 14. Zodiac signs. The painting of the wooden synagogue in the city of Khodorov (has not been preserved). Conjugations (unions) of nearby codes complicate the final meanings, giving them expanded variants of meanings. Combining three of the four codes from each of the four sides (shown in bright yellow in the diagram) reveals through the synthesis of symbols four key meanings of Jewish culture: Creation, Paradise, Torah personas and the expectation of the Messiah. The central conjugation of all five codes is an Eye (in semantic meaning, as well as a visual similarity with the eye is read on the diagram), or the Heart of Judaism, its central meaning accumulating all ideological ideas, the visual (pictorial) embodiment of which, invariant for all Jewish peoples of the Crimea, is the synagogue Aron Hakodesh – a cabinet for storing a scroll Torahs (Fig. 3, 4) [8]. The traditional composition of Aron Hakodesh embodies the Ark (Tabernacle) of the Covenant, as well as the Holy of Holies of the First and Second Temples – the storage place of the tablets, and later the written Torah. The place for storing the Torah in the synagogue (kenase, kaale) is decorated in the form of a portal – the entrance to Paradise, framed by two columns (images of the temple columns Yahin and Boaz) – the Number code, Menorah. On the sides of the portal are often placed the symbols of the guardians – lions, or a lion and a unicorn – the code Bestiary. Plants, flowers and fruits in the upper part of the Aron Hakodesh represent the Garden of Eden – the code Rimon. In the upper part of the portal, the symbol of God as the royal authority is depicted – a lion, an eagle – the Bestiary code, or a crown – the Menorah code. Images of Torah tablets are placed above the portal – Sefer codes (Book), Menorah, Numbers. Such a composition with small variations is also often found in the design of marriage ktubbots or shetars – marriage contracts, pinkas – charters of various organizations, makhzors – festive prayer books, as well as in the decoration of ceremonial objects – embroidered curtains-parochets, dishes, shields for separating the heads of the Torah – tass, tombstones – mats.Thus, the codes of the Jewish visual semiosis highlighted by us are invariant, their source is the Book of Torah, as the basis of the entire religious Jewish doctrine. Each of the codes is a group of characters united by a Book code. The conjugations of codes and their combinations show a cycle from the common primary source – the Torah, to it – the Torah as a shrine, both in eschatological and material incarnation. A stable composition, passing from one artifact to another, indicates Judaism, and the interpretation of individual symbols makes it possible to decipher the cultural text. A number of connotations in the pictorial semiosis of the three Jewish ethnic groups of Crimea are insignificant, and relate more to folk mythology, whereas in the religious tradition the totality of visual codes is practically invariant and corresponds to their single primary source [8].

The bestiary code represents a fairly wide range of images of fauna, symbolizing people, their qualities, as well as the plots of the Torah or Talmud. Their symbolism is stable, invariant for representatives of different directions of Judaism. The images of the bestial code are most common in the Ashkenazi environment, especially among the Hasidim, while the Sephardim, influenced by nearby Islamic cultures, focus on the Rimon code and Numbers, and stylistically their visual culture tends to geometric ornamentation. It should be noted that the codes of the Jewish pictorial semiosis (in the conditions of the dispersion of Jewish communities around the world, different cultural and linguistic environments), serve as the most unambiguous identifiers of mentality, reminders of Old Testament habitations. The scheme showing the relationship between the codes is also suitable for the systematization of codes of the visual semiosis of other cultures, however, of course, in this case it is subject to correction of the names of codes (groups of symbols), as well as the meanings of their interaction, in accordance with another cultural source.Figure 15.

Traditional Aron-Hakodesh. Synagogue in Safed, Israel.

Figure 16. Traditional Aron-Hakodesh.

References

1. Danilevsky V. Ya. 2011. Russia and Europe. A look at the cultural and political relations of the Slavic world to the Germanic-Romance. Moscow : Institute of Russian Civilization. 813 p.

2. Jews. 2018. Moscow: Nauka. 783 p.

3. Kanzedikas A. 2001. Album of Jewish artistic antiquity by Semyon Ansky. M. : Bridges of Culture. 336 p.

4. Kizilov M. B. 2011. Crimean Judea: Essays on the history of Jews, Khazars, Karaites and Crimeans in Crimea from ancient times to the present day. Simferopol: Dolya. 336 p.

5. Kizilov M. B. 2014. Krymchaks: a review of the history of the community // Jews of the Caucasus, Georgia and Central Asia: studies in history, sociology and culture. Moscow : Ariel. Ð. 218-237.

6. Kozlov S. Ya. 2000. Judaism in Russia: History and modernity // Research on applied and urgent Ethnology. Moscow : IEA RAS. Issue 137. Ð. 3–27.

7. Kotlyar E.R., Alekseeva E. N. 2022. The Jewish cultural code in the visual semiosis of Crimea // Philosophy and Culture. No. 11. pp. 7 - 29. DOI: 10.7256/2454-0757.2022.11.39195 URL: https://nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=39195

8. Kotlyar E. R. 2015. Craft and Torah: sources, types and repertoire of Jewish traditional art. // Collection of the Kemerovo State University of Culture and Arts. Kemerovo: KemGUKI. No.31. Ð. 68-76.

9. Lotman Yu. M. 2000. Semiosphere. St. Petersburg: Iskusstvo-SPb. 704 p.

10. From the Cimmerians to the Krymchaks. 2014. The peoples of the Crimea from ancient times to the end of the XVIII century. / edited by I. N. Khrapunov, A. G. Herzen. Simferopol: Phoenix. 286 p.

11. Pierce Ch. S. 2001. Principles of philosophy. St. Petersburg : St. Petersburg Philosophical Society. Vol. II. 320 p.

12. Saussure F. de. 1977. Course of general linguistics // Proceedings on linguistics. M. : Progress. Ð. 31–269.

13. Stasov V. V. 1872. Russian folk ornament. Issue 1. Sewing, fabrics, lace. St. Petersburg : Society for the Encouragement of Artists. 88 p.

14. The Turkic peoples of the Crimea. Karaites, Crimean Tatars, Krymchaks. 2003. M.: Nauka. 459 p.

First Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

The subject of the study, the cultural code "Bestiary" in the Jewish pictorial semiosis, is considered by the author in a religious context based on the analysis of "the holy books, including the Torah (the Pentateuch of Moses), Neviim (the Books of the Prophets) and Ktuvim (Scriptures), which are the basis of Judaism as a creed" ("The Safer Code includes all key verbal sources that are the basis of Judaism"). It is the presence of references in the Sphere of various bestiaries that allows the author to identify a separate sign (artifact) as a symbol or code of Jewish culture, as well as to reveal its "bookish" (cultural) meaning. The strength of the article is a detailed study of most of the concepts used, including their geography and ethnography. Thus, the author excludes discrepancies in the understanding of the described aspects of reality and possible speculations regarding the cultural characteristics of the studied artifacts. At the same time, one of the key concepts characterizing the object of research, semiosis, is not specifically defined by the author, but emerges from the context. On the one hand, the author understands semiosis as a historical process of the emergence and evolution of meanings; in this sense, the historical and geographical certainty of the origin of the main sources (Sfarim), as well as their regional and ethnographic "refractions" (features), is valuable. On the other hand, the restoration of the logical relationship of signs and their meanings leads to the concept of semiosis as a logically structured abstract system of meanings (semiosphere), which allows the author to interpret the meanings of individual signs. In general, this dualism does not lead to contradictions, both approaches complement each other and allow the author to reveal the subject of research at a decent theoretical level. The research methodology is cemented by general scientific methods of typology and classification of various objects of symbolic reality, reinforced by separate semiotic techniques and a comparative historical method. The bold, and at the same time the most controversial, author's solution is the visual typology of the codes of "traditional images concerning Jewish culture", represented by Euler circles. With the help of Euler's circles, the author identifies five codes, "with the help of which the main meanings of any traditional images concerning Jewish culture are revealed," giving them names, again remaining in the ethno-national religious semiosphere. On the one hand, using the above scheme, the author indicates five areas (types) of pictorial signs, among which bestiaries occupy a certain position. But at the same time, questions arise: 1) how fully does the structure of the ratio of sets of values formed with the help of Euler sets reflect? 2) what does it mean to place the author in the center of the intersection of the sets of the "Eye of God"? 3) is it not more traditional for Jewish culture to symbolically reflect the sets in the hexagram of the Star of David? — and others . However, a new method or technique always raises a lot of questions. Probably, the author's subsequent publications will reveal the heuristic potential of his methodological innovation in full. The reviewer recommends that when using a drawing in the text, it should be designed, including the title, based on the relevant GOST. The weak points of the author's approach remain: 1) the lack of an assessment of the study of the problem (in the existing context, the problem looks as if no one had dealt with Jewish culture or bestiaries before the author); 2) the lack of an assessment of the applied significance of the result obtained. The latter circumstance, taking into account the scrupulous, almost dictionary-like, consideration of individual concepts by the author, creates a disproportion of the final conclusion in relation to the large introduction and the detailed main part. The reviewer recommends that the author strengthen the final conclusion by evaluating the achievement/ non-achievement of the research goal, the theoretical and practical significance of the result obtained, the novelty of the research (added new scientific knowledge). The relevance of the topic of cultural codes is always due to the problems of intercultural communication. Due to the intensification of cultural integration processes in the modern world, the use of traditional symbols prevents insinuations and speculation around cultural signs and symbols. Perhaps, if, during revision, the author takes into account the reviewer's comment on the applied significance of the results obtained, the relevance of the publication of the presented article can be justified more argumentatively. The scientific novelty of the results was achieved by the author, first of all, due to the typology and classification of symbolic objects of Jewish culture. This allowed the author to logically conclude that "The bestiary Code represents a fairly wide range of images of fauna, symbolizing people, their qualities, as well as the plots of the Torah or Talmud. Their symbolism is stable and invariant for representatives of different branches of Judaism." The author's visual typology of codes could also be attributed to the element of scientific novelty, but for its further application there is not enough elaboration of a significant heuristic potential and the limits of applicability of the innovation (is it possible, for example, to use the author's technique in the analysis of other cultures, other types of signs?). The style in general in the work is scientific, although there are some comments: 1) it is necessary to subtract the text for unnecessary spaces before punctuation marks, as well as missing spaces between words; 2) in the phrase "the thesis was confirmed by other ethnographers" there is an obvious error of agreement; 3) in the statement "The initial description of cult objects is described in the Torah in the form of prescriptions ..." it is difficult to read the author's thought becausefor tautologies and errors of agreement: the description is described in the form of prescriptions." The structure of the article as a whole reflects the logic of presenting the results of scientific research, although, as the reviewer has already noted above, it is desirable to strengthen the conclusion and assess the degree of study of the problem and the applied significance of the result obtained. The bibliography is described according to editorial requirements and generally reflects the problematic area of research, although a small review of scientific literature on the topic, including foreign literature, over the past 5 years would significantly enhance the scientific significance of the publication and attract more attention to it from specialists. The appeal to the opponents is correct and sufficient. The interest of the readership of the journal "Philosophical Thought" in the article is guaranteed, but it may be more significant after the revision of the article, taking into account the comment of the reviewer.

Second Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

The author submitted his article "The cultural code "Bestiary" in the Jewish Pictorial Semiosis" to the journal Philosophical Thought, which examines the commonality and connotations of Jewish symbolism in pictorial practice using examples of artistic artifacts of the second half of the XIX – first third of the XX centuries. The author proceeds in the study of this issue from the fact that the structuring of the Jewish cultural code is impossible without referring to the fundamentals of Jewish religious beliefs. Based on the work of N.Y. Danilevsky "Russia and Europe", the author defines religion as the basis of the ethnic identity of the people, in particular, the peoples professing Judaism. Based on the confessional feature, the author identifies the following Jewish ethnic groups: Ashkenazi Jews, Karaites, and Crimeans. The relevance of this issue is due to the fact that in the period of universal globalization and the blurring of identity boundaries associated with active interaction through modern means of communication, the development of ethnic monoconfessional cultures faces a number of problems. On the one hand, this is the problem of preserving identity and further developing national traditions related to religion, language, and folk art, and on the other hand, the problem of tolerance, constructive dialogue and interaction between representatives of different peoples. The theoretical basis of the study was the works of such world-famous researchers as Yu.M. Lotman, N.Ya. Danilevsky F. de Saussure, W. Eco, A.J. Flier, et al. The methodological basis of the study was an integrated approach containing historical, socio-cultural, semiotic, comparative and artistic analysis. The purpose of this study is a comparative semantic-symbolic, typological and stylistic study of the works of decorative and applied art of Jews: Jews, Karaites and Krymchaks, as well as an analysis of stable symbols based on a single source underlying the religion of each of the designated ethnic groups - the Torah, which displays both common ethnocultural origins and the uniqueness of each the ethnic group. Having conducted a bibliographic analysis of the studied issues, the author notes that interest in the artistic side of the Jewish tradition arose at the end of the XIX century, when, due to urbanization and the desire of young people to cities, towns began to fall into disrepair. The ethnographic expeditions undertaken in order to preserve the cultural heritage, led by ethnographers, marked the beginning not only of ethnographic collections of household and ceremonial Jewish objects, but also of the study of pictorial Jewish semiosis. As noted by the author, all researchers considered bestial plots in a general historical and cultural context, without singling them out in a separate direction. The systematization of the range of traditional images and their interrelationships, their consideration from a generalized philosophical, culturological position is the scientific novelty of this study. The author pays special attention to the analysis of the concept and essence of visual semiosis as an important component of artistic culture and semiotics in general as a philosophical trend. Also by the author based on the works of W. Eco and Y.M. Lotman, A.Ya. Flier and other prominent Russian cultural scientists present an analysis of the theory of cultural text, as well as the unified mechanism of semiotic space in the context of culture. The author also defines the essence of the concept of "cultural code", gives its definitions and functions. Having studied an extensive layer of artifacts, the author presented the codes of the Jewish pictorial semiosis in the form of a scheme like Euler circles, which allows us to visually identify the relationships between subsets by superimposing planes on each other. The author identifies and describes in detail five codes that identify the main meanings of any traditional images related to Jewish culture: the Sefer code (key verbal sources that are the basis for all Jewish postulates); the Menorah code (skewomorphic images of Jewish cult attributes); the Rimon code (phytomorphic images); the Number code (numerical symbolism), code Bestiary (zoomorphic and zooanthropomorphic images, both real and mythological). As presented by the author in the diagram, combining three of the four codes from each of the four sides reveals through the synthesis of symbols the four key meanings of Jewish culture: Creation, Paradise, the person of the Torah and the expectation of the Messiah. The central conjunction of all five codes represents the Eye or Heart of Judaism, its central meaning, accumulating all ideological ideas. The author pays special attention to the analysis of the Bestiary code. According to the author's conclusions, the bestiary code represents a fairly wide range of images of fauna, symbolizing people, their qualities, as well as subjects of the Torah or Talmud. Their symbolism is stable and invariant for representatives of different branches of Judaism. The most common depictions of the bestial code are in the Ashkenazi environment, especially among Hasidim, whereas the Sephardim, influenced by nearby Islamic cultures, focus on the Rimon code and Numbers, and stylistically their visual culture tends to geometric ornamentation. As the author states, the Jewish bestiary carries an allegorical meaning, each of the images is the personification of God, man or his individual qualities. Images of symbolic animals mentioned in Scripture are most often found in three types of compositions: This is the canonical composition of Aron Hakodesh in the form of a portal, where the niche for storing the Torah is guarded by animal guards, and birds are depicted in the branches of the paradise tree above the portal; Ashkenazi tombstones are matzevs; the Zodiac, borrowed by the Jews and interpreted as the personification of the twelve main holidays. The author conducted a descriptive and semiotic analysis of the meanings of images of animals that occur most often: lion, eagle, bull, griffin, unicorn, leviathan, elephant, deer, stork, bear, pigeon. In conclusion, the author presents the conclusions of the study, including all the key provisions of the presented material. It seems that the author in his material touched upon relevant and interesting issues for modern socio-humanitarian knowledge, choosing a topic for analysis, consideration of which in scientific research discourse will entail certain changes in the established approaches and directions of analysis of the problem addressed in the presented article. The results obtained allow us to assert that the study of the peculiarities of the formation of a single cultural code of a separate monoconfessional ethnic group and its representation in the samples of artistic culture is of undoubted theoretical and practical cultural interest and can serve as a source of further research. The material presented in the work has a clear, logically structured structure that contributes to a more complete assimilation of the material. An adequate choice of methodological base also contributes to this. The bibliographic list consists of 14 sources, which seems sufficient for generalization and analysis of scientific discourse on the studied problem. It can be said that the author fulfilled his goal, obtained certain scientific results, and showed deep knowledge of the studied issues. It should be noted that the article may be of interest to readers and deserves to be published in a reputable scientific publication.

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|