|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

Litera

Reference:

Jing R.

The spread of modern Russian female novel in China

// Litera.

2022. ¹ 6.

P. 151-163.

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8698.2022.6.38282 EDN: PPTYZJ URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=38282

The spread of modern Russian female novel in China

Jing Ruge

ORCID: 0000-0002-1341-0039

PhD in Philology

Research Assistant, Institute of Foreign Languages, Shanghai Jiaotong University,

200240, Kitai, Shankhai oblast', g. Shankhai, ul. Dunchuan', 360, kv. 6

|

jingxiao777777@yandex.com

|

|

|

|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8698.2022.6.38282

EDN: PPTYZJ

Received:

17-06-2022

Published:

04-07-2022

Abstract:

The article is devoted to the problem of the spread of Russian female novel in China from the end of the 20th century to the present day. The subject of the study is the translation and publication of modern Russian female writers in China. The purpose of the article is to identify patterns of the spread of modern Russian female novel in Chinese society. Using descriptive, analytical and comparative methods, the author tries to analyze the phenomenon of the spread of Russian female novel in China on the basis of Leo Leventhal's theory of literary communication. The author examines in detail such aspects of the topic as the peculiarities of the periodization of the spread of Russian women's prose in China, the main influencing factors in the distribution process, as well as the evaluation of the works of Russian female writers by the Chinese audience. Many studies discuss the perception of the Chinese audience of the works of such Russian writers as L. E. Ulitskaya, T. N. Tolstaya, but the general pattern of the spread of Russian female novel in China has been little studied. The scientific novelty of this work lies in the fact that it for the first time comprehends the process of the dissemination of the works of Russian female writers in China from the point of view of communication. Chinese Russianists are still the dominant force in the distribution of Russian female literature in China, but as the Chinese reading market of Russian female novel is being formed, the influence of readers is becoming stronger.

Keywords:

russian female literature, russian female writer, literary communication, literary exchange, China, chinese russianists, perception of literature, chinese readership, distribution model, translation

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

Introduction Russian Russian women's prose as an offshoot of diverse Russian literature serves as an important link in literary communication between China and Russia. There are a number of works on the problem of research and perception of the works of Russian writers by the Chinese audience. Zhao Xue is the author of an article on the perception of L. Ulitskaya in Chinese Russian studies[1], in collaboration with Yu. A. Govorukhina, Zhao Xue identifies factors influencing the interpretation and evaluation of modern Russian women's prose by Chinese Russian writers[2]. The article by Zou Luwei and M. V. Mikhailova talks about the perception of A. A. Akhmatova in China[3]. Zhuge Jing and I. V. Monisova in their work summarized the state and history of research of Russian women's prose in China[4]. But the problem of general patterns of the spread of Russian women's prose in the aspect of communication still needs further research. According to Leo Leventhal, "literature itself is a means of communication" [5, p. 11], literary communication is carried out in the force fields of a three-way game between the communicator, society and the recipient. Therefore, when literature is distributed through translation in a foreign country, the author ceases to be the sole creator of works, because the communicator, society and the reader become participants in the process of reconstruction of works. The reputation of writers and the perception of their works in foreign countries mainly depend on how this reconstruction process is going. Proceeding from this, the dissemination of modern Russian women's prose in China is, in fact, an act of communication that acts through communicators (that is, Chinese Russianists or translators), society (publishing house and media) and readers (professional and non—professional). In China, two stages of the spread of modern Russian women's prose were observed: at the first stage, L. Petrushevskaya, L. Ulitskaya, T. Tolstaya, V. Tokareva, A. Marinina, D. Dontsova came to the attention of the Chinese audience, and at the second stage O. Slavnikova, E. Chizhova, S. Alexievich, G. Yakhina, D. Rubina gained fame in China, E. Alexandrova-Zorina, E. Kolyadina, M. Stepanova. In the process of distributing the works of the above—mentioned writers in China, the transformation of their perception model is noticeable - from a Russian-oriented to a market-oriented one. To clarify this communication process, it is necessary to understand the two stages of the spread of modern Russian women's prose in China. The first stage of the spread of Russian women's prose in China In the last century, the model of Chinese society's perception of Russian literature of the twentieth century has long been a model of binary opposition, the purpose of which was to emphasize the inherent political correctness of literary works, to evaluate the literary value of works from the point of view of class antagonism. The reason for the formation of such a model is that the class struggle was introduced into cultural and literary criticism as a mandatory principle. Due to the policy of reforms and openness of the XXI century, the Chinese academic community gradually began to abandon this model, and there was a "thaw" in the dissemination of foreign literature in Chinese society. The Chinese perception of Russian literature has transformed from a unification model into a diversification one, which is characterized by "efficiency and scientific" [6, p. 82]. Russian Russian literature, banned literature, mass literature and other literatures have enriched and expanded the views of Chinese readers about Russian literature. In a word, now "Russian literature is going through the best period in China, because we consider it only as literature proper" [7]. From the 1990s to the early 2000s, when Chinese scientists got acquainted with new trends in the development of Russian literature, the first group of women writers came to their attention - L. Petrushevskaya, L. Ulitskaya, T. Tolstaya, V. Tokareva, A. Marinina, D. Dontsova. Russian Russian writers Zhang Jianhua was the first to introduce these Russian writers to the Chinese audience in literary magazines in the article "On the aesthetic features of the transition period in the development of Russian novels" (1995) mentioned the work of L. Petrushevskaya and T. Tolstoy, noted that their works contain aesthetic characteristics of the new Russian novel, namely the emphasis on "their own feelings about life around them" [8, p. 89]. Russian Russian Literature In 1996, the collection of short stories "Poor Relatives" by L. Ulitskaya was named as a vivid example of Russian literature of the new era in Yan Yongxing's article "A Brief Overview of the Situation of Russian Literature in 1995". The earliest interview with V. Tokareva was published in the Chinese feminist magazine "Women's Literature" (1986), then the Russianist Fu Xinghuan wrote an article "The Clash of gender Worlds" (1997), devoted to the study of feminism in Tokareva's novel "Avalanche". From the 80s of the twentieth century to the beginning of the XXI century, translations of the works of the aforementioned writers were published in such Chinese literary newspapers as "Russian Art and Literature", "Foreign Literature" and "World Literature": "Between Heaven and Earth" (1986), "Love and Travel" (1989), "Pickaxe and Officer" (1992), "Happy Ending" (1999), "Avalanche" (1997) by V. Tokareva; two stories by T. Tolstoy "Sonya" and "Sweet Shura" (1993); "Girls" (1994) and "Sonechka" (1997) by L. Ulitskaya; "The Music of Hell" (2001), "The Nose Girl", "The Tale of the Clock", "New Hamlets", "Donna Anna, the Stove Pot" (2003) by L. Petrushevskaya. The enthusiasm of Chinese Russianists in the translation of Russian literature quickly spread to the publishing world. Since 2005, Chinese publishing houses began to translate and publish the works of these writers separately: T. Tolstoy's novel "Kys" (2005) was published; then L. Petrushevskaya's novels "Number One, or In the Gardens of Other Possibilities" (2012), "Time is Night" (2013), "Labyrinth" (2015); novels by L. Ulitskaya "Sincerely Yours, Shurik" and "Medea and her Children" (2005), "Childhood forty-nine" (2006), "Jacob's Ladder" and "Kukotsky's Incident" (2018), "Sonechka" (2020), "Girls" (2021), "Fun Funeral" (2021).

A. Marinina and D. Dontsova became familiar to the Chinese audience a little later. After the article "The most popular Russian writer of detectives", published in 1998 in the authoritative newspaper Reference News, A. Marinina became famous. From 1999 to 2001, the peak of translations of A. Marinina's works came: "The Confluence of Circumstances" (1999), "Involuntary Killer" (1999), "Death for Death's Sake" (1999), "I died yesterday" (1999), "Death and a little Love" (1999), "The Game on someone else's field" (2000), "Men's Games" (2001), "The Ghost of Music" (2001), "Stolen Dream" (2001), "Blacklist" (2001). A little later, according to the Russian scholar Zheng Jie, she came to the attention of Chinese publishers and D. Dontsov. She was presented in China as "a vivid example of Russian female detective authors" [9, p. 26]. Her novel "The Harvest of Poisonous Berries" (2005) became the only work translated into Chinese and published. Dontsova's other works: "Cool Heirs" (2006), "A Real Christmas Tale" (2010) and "A Gift for Grandma" (2018) were only translated and published in Chinese in the literary magazine "Yilin", and not as a separate book. At the first stage of the boom in the spread of Russian women's prose in China, L. Petrushevskaya, L. Ulitskaya, T. Tolstaya and V. Tokareva occupied a dominant position, and in this process the role of Chinese Russianists was especially highlighted. The table below compares the years of publication of scientific articles, writing of student papers and publications of the first translation. The data were collected from Chinese Internet sources [?] from the 90s of the twentieth century to 2022, based on a comparison of which some patterns can be noticed. | The name of the writer at the first stage of the distribution boom russian women 's prose | The year of publication of the first scientific articles devoted to the writer's work | The year of writing the first student studies devoted to the writer's work | Year of publication of the first translation | | V. Tokareva | 1997 | 2001 | 1999 | | L. Ulitskaya | 1999 | 2001 | 1999 | | L. Petrushevskaya | 2003 | 2006 | 2012 | | T. Tolstaya | 2004 | 2014 | 2005 | | A. Marinina |

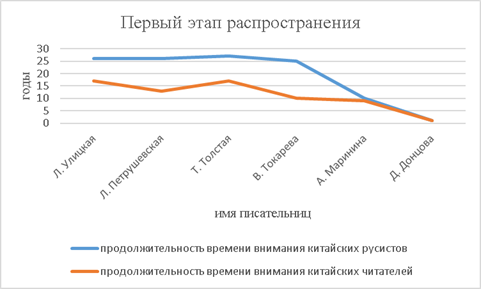

2000 | 2017 | 2000 | | D. Dontsova | 2003 | 2017 | 2005 | In most cases, Chinese Russianists, as a rule, were the first to pay attention to the works of writers, then publishers reacted and, finally, the student audience. Thus, it is obvious that the scientific research of Chinese Russianists was the first driving force that contributed to the spread of Russian women's prose at the first stage. Comparing the number of scientific articles devoted to writers, student papers and the number of translations, we can note an interesting relationship between these three factors, as shown below:

The attention of Chinese Russian scholars to the works of Russian writers, the research interest of the student audience in their works and the number of translations form a positive correlation with each other. This suggests that the leading factor in the popularization of women's prose are Chinese Russian writers, the breadth of distribution of the works of writers in Chinese society mainly depends on their recommendations. Further, if we compare the duration of scientists' attention by time (number of years) and the time interval of Chinese readers' reactions (number of years during which comments are received), then we can see that these two factors also reveal a certain pattern, as shown below:

As can be seen from the graph above, the research interest of scientists is proportional to the attention of readers to a particular work, which means that both scientists and readers have a high degree of consistency in the perception of literary works. This to a certain extent indicates the homogenization of the audience of Russian women's prose at this stage. Russian Russian students, students of the specialty "Russian language" and lovers of Russian literature, i.e. professionals, were the main audience. The reason for the formation of such a distribution model is that, being a little-known direction in literature, Russian women's prose has not yet been fully appreciated, so at first the scope of its distribution was limited to a circle of professional readers, among whom the priority belonged to Chinese Russian writers. The second stage of the spread of Russian women's prose in China In China, the second stage of the spread of modern Russian women's prose has been observed since 2007. Women writers - O. Slavnikova, E. Chizhova, S. Alexievich, G. Yakhina, D. Rubina, E. Alexandrova—Zorina, E. Kolyadina, M. Stepanova - came to the attention of Chinese readers. O. Slavnikova played the role of a link between the first and second stages of the spread of women's prose in China. She became the second Russian writer since 2000 to receive the Chinese award "Best Foreign Novel of the Year in the XXI Century", the first was L. Ulitskaya. Russian Russian prose's success showed that the spread of Russian women's prose in China is moving from the previous stage to the next — L. Ulitskaya (2005) and O. Slavnikova (2011) won this important award one after another, which meant that the work of Russian writers was recognized not only by Chinese Russianists, but also by Chinese literary experts-specialists in foreign literature.. The attention of the Chinese media to Slavnikova appeared immediately after she received the Booker Prize in 2006, in 2007, the famous Chinese magazine Dynamics of Foreign Literature published an interview with O. Slavnikova. In 2011, there was a boom in China in the fascination with her works in translations: "2017" and "Light Head". Slavnikova's novels remind Chinese readers of George Orwell's dystopian novel. Following Slavnikova, another winner of the "Russian Booker" in 2009, Elena Chizhova, appears on the reader's horizon, her novel "The Time of Women" (2013) was the only one translated and published in China.

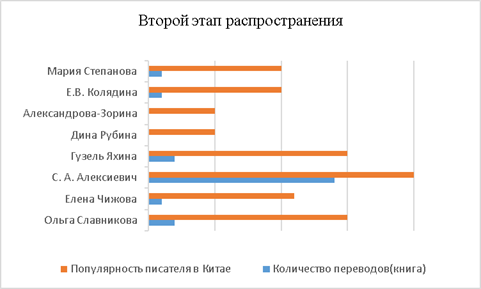

S. Alexievich in 2015, as the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, immediately attracted attention from the Chinese book market. Her works have long been known in the West, since the 80-90s of the twentieth century, but only since 2014 began to be published in China. Thanks to forecasts in the field of international literary awards, Chinese publishers in 2014 have already published 2 books dedicated to this potential laureate. The passion for translating and studying the works of S. Alekseevich has appeared since 2015: "Zinc Boys" (2015), "Chernobyl Prayer: Chronicle of the Future" (2015), "The best selected Works of Svetlana Alexievich" (2015), "Second-hand Time" (2016), "War does not have a woman's face" (2020), "The Last Witnesses: one hundred non-childish stories" (2020). Russian Russian scholars consider Alexievich as a successor to the traditions of Russian classical literature of the XIX century and believe that her works contain a "deep humanistic narrative" [10, p. 10], "moral strength" and "the legacy of the spirit of the Russian intelligentsia" [11, p. 17]. From the point of view of Chinese literary critics and readers, these features are typical of the pen of classical Russian writers. After G. Yakhina received a number of such important literary awards in Russia as The Big Book, Yasnaya Polyana and Book of the Year, she acted as a new representative of modern Russian women's prose, and her works began to be translated in China. In 2017, in the Chinese newspaper Literature and Art, Russian scholar Liu Wenfei rated the work "Zuleikha opens her eyes" as "the best Russian novel since the collapse of the Soviet Union" [12]. The hard story and humanistic spirit of the novel "Zuleikha opens her eyes" by Yakhina remind Chinese readers of the "Red Poppies" by the Tibetan writer Alai. It was this year that Yakhina won the Chinese award "The Best Foreign Novel of the Year in the XXI Century". Thanks to this, she became the third Russian female laureate of this award after L. Ulitskaya and O. Slavnikova. Since 2017, Chinese publishers have started translating and publishing her novels: "Zuleikha opens her eyes" (2017) and "My Children" (2020). D. Rubina as one of the most popular Russian writers has long been known in the book market of Russia and abroad. In China, her story "At Your Gates" was translated into Chinese for the first time back in 1995, but interest in her works in the Chinese literary world began to grow only since 2017. Since this year, her stories "The Murderer" (2017), "Master Tarabuka" (2017), "High Water of the Venetians" (2017) have been alternately translated in literary magazines. Her novels "On the Sunny Side of the Street" (2017) and "Parsley Syndrome" (2020) were published. In 2020, an interview with Dina Rubina was published in the Chinese magazine "Modern Foreign Literature", which showed the growing attention of Chinese literary critics to her. E. Kolyadina with her novel "Flower Cross" attracted the attention of Chinese Russian scholars back in 2011, but this became her only work translated and officially published in China in 2017. Due to the "eroticism" and "religious overtones", Kolyadina's novel became controversial, its assessment among readers and Russian scholars in China turned out to be ambiguous. "The destruction of human nature by religious rule", "the contradiction between sexual instinct and religious faith" are the main impressions of readers. But according to Russian scholars, the novel shows "the important rhetoric of the narrative of modern Russian prose — a hypothetical metaphor combining historical facts and artistic fantasy" [13, p. 359]. Similarly, in 2017, individual stories by E. Alexandrova-Zorina were translated by Chinese Russian scholars: "Elisha Kuzmich", "Architect of Castles in the Air", "Provincial Rhapsody", "Evil City" — but were published only in a magazine version. The works of M. Stepanova became familiar to the Chinese audience after 2019. In 2018, the collection "Memory of Memory" received rave reviews from literary critics and the "NOSE" and "Big Book" awards. Her literary reputation immediately attracted the Chinese publishing industry, and in 2019 the Publisher magazine introduced Chinese readers to information about this award-winning novel. In 2020, the publishing house of the Chinese corporation CITIC released "Memory of Memory". Russian Russian women's prose At the second stage of the spread of modern Russian women's prose, it became noticeable that the Chinese publishing industry began to dominate the promotion of Russian women's prose and, as a rule, preferred to publish award-winning works. To clearly demonstrate this trend, let's compare the following two factors — the popularity of the writer and the number of translations of his works, as shown below:

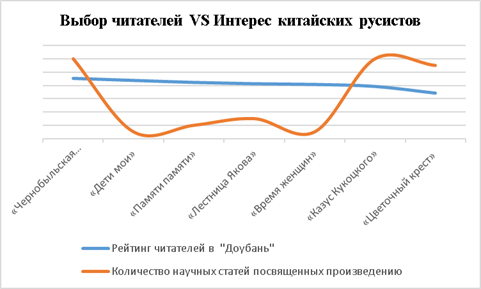

(1) The first graph shows the relationship between the number of translations and the popularity of the writer in China (taking into account the number of newspaper reports about the writer and the Chinese literary awards she received). Obviously, the more famous the writer, the more her works have been translated, for example: S. Alexievich, G. Yakhina and O. Slavnikova. It also reflects the fact that in the case of the dominance of the publishing house in the market, the fame of writers has become more important than the research value of the works themselves. Compared with the recommendation of Chinese Russian scholars, such awards as "The Best Foreign Novel of the Year in the XXI century", "Nobel Prize in Literature", etc. are more important for Chinese publishers. | Readers' Choice VS The Interest of Chinese Russianists (data) | | Composition |

Reader Rating / score | The number of scientific articles devoted to the work | | "My children" | 8.8 | 1 | | "Memory of memory" | 8.5 | 2 | | "Jacob's Ladder" | 8.3 | 3 | | "Women's Time" | 8.2 | 1 | | "The Kukotsky Incident" | 7.9 | 12 | | "Flower Cross" | 6.9 |

11 |

(2) The second graph shows that there is not always a directly proportional relationship between the readers' assessment of works and the number of scientific articles devoted to the same works. For example, from 2010 to 2020, the novels "My Children", "Memory of Memory", "Jacob's Ladder", "Time of Women" were highly appreciated by Chinese readers in the social network of readers of the books "Doban", but at the same time the interest of Chinese Russian writers in these novels was relatively small (on average, there are from 1 to 2 research papers for each novel). Apparently, the readership has formed its own taste, which differs from the opinion of Chinese Russian writers, the reader's perception of Russian women's prose is no longer so strongly influenced by the recommendations of researchers. To some extent, this is a reflection of the fact that the model of literary communication aimed at Chinese Russianists is changing, and publishers and readers are beginning to influence the process of spreading Russian women's prose more. The trend of the spread of Russian women's prose in China: from the first to the second stage In the era of mass communications, "literature is a synthesis of two directions: one is creativity, the other is a market—oriented product" [5, p. 13]. Therefore, in China, modern Russian women's prose has a double function: on the one hand, it turns out to be a carrier of literary and artistic thought, and on the other — a literary commodity, the demand for which depends on the market. The success of the spread of Russian women's prose in China largely depends not on the talent of the author himself, but mainly on how "communicators" convey these works to Chinese society and Chinese readers. To better understand who exactly plays the role of "communicators", it is necessary to find an answer to the question: how does a literary work find recognition in China? "Although there are many factors, but the main ones are three: the literary market, the literary critic and university textbooks on literature" [14, p. 47]. In general, the value of Russian women's prose is first approved by Chinese scientists, and then transmitted to Chinese society through the intermediary of the literary market — the publishing industry. When these works finally pass the test of both time and Chinese political ideology, they are included in university textbooks. Judging by the two stages of the spread of modern Russian women's prose in Chinese society, undoubtedly, its first recognition in the Chinese market is inseparable from the recommendations of Chinese Russian writers, such a trend was observed at the first stage. But as a stable group of readers and market demand were formed, the leading role of Chinese Russianists gradually began to weaken, new communicators in the face of publishers and readers began to dominate the process of distributing prose. This changing situation was shown in the second stage. The changing patterns of the process have shown us two important trends: the model of the spread of modern Russian women's prose in China is traditional, and that its group of readers continues to expand. About the model. From the point of view of literary communication, the model of the spread of modern Russian women's prose in China can be considered as a model of communication that is carried out through cultural exchange between the two countries.Because the market for readers of Russian literature is so limited compared to English and Japanese literature that it cannot serve as a reference point for the publishing industry. And the judgments of Russian scientists turned out to be more significant, including the reputation of the writer, hence the assessment of Chinese Russian scientists and the number of relevant studies — all this serves as a guarantee of profit for the Chinese publisher. In this regard, the communication model is still more traditional, that is, first the works are checked by professionals, and then distributed in China. This communication model has a long history in China. Since the spread of knowledge about foreign cultures, Chinese intellectuals have played a leading role in the selection, formation of public opinion and dissemination of information. Russian Russian literature, including Russian women's literature, as a form of art and professional literary knowledge, without the interpretation and recommendation of Chinese intellectuals, as a rule, it is difficult to distribute among the Chinese readership. About readers. Based on the changing trends from the first to the second stages of the spread of Russian women's prose, the leading role of Chinese Russianists has gradually been replaced by the key role of the market, a group of readers is gradually forming its own evaluation system, literary works have begun to turn from a certain kind of art into a commodity for entertainment or self-education, so the demand of readers in the future will play an important role. What do Chinese readers expect from Russian women's prose? Russian Russian literature audience in China consists of two groups, namely professional readers — they are mainly Russian speakers and students of the Russian language, and non—professional readers - they are lovers of literature. As for Russian women's prose, she has another special reading group — it's only women. Different groups of readers pursue different reading goals. For most non-professional readers, the attractiveness of Russian women's prose, like any kind of foreign literature, lies in an alternative perspective for learning about the world and Russia. Russian Russian is a new opportunity for professional readers to expand their knowledge of the Russian language and Russian culture. Russian Russian women's prose provides a channel for Chinese readers to express themselves and reflect on what Russian writers have written about women's happiness and personal problems. And their arguments about social history also became a source of formation of the ideology of feminism among Chinese women. The audience of Russian literature in China is characterized by diversification and segmentation. Therefore, as the number of readers increases in the future, to a certain extent the leading role of scientists in the dissemination of Russian literature will weaken, and the publishing house will value the role of a "communicator" in the face of readers more. Conclusion

Russian Russian women's prose began to be published in China more than 30 years ago, its distribution has already become a significant literary phenomenon in the Chinese-Russian literary exchange. The model of the spread of Russian women's prose in China as a whole is as follows: scientists, experts and authorities from the point of view of literary studies play a leading role in the distribution process, and society and readers are often passive recipients. Therefore, the way of spreading modern Russian women's prose in China consists of three points — a Chinese Russian, a publishing house (including media), a reader. And the direction of communication is from top to bottom. However, a new trend is emerging in the transition from the first to the second stage: the dominance of Chinese Russian speakers is weakening, and a reader-oriented market is gradually forming. This undoubtedly shows the success of Russian women's literature in China, while the number of non-professional readers is constantly growing. At the further stage of popularization of Russian women's prose in China, it is necessary to pay great attention to the perception of non-professional readers. Distribution channels should be broad and more independent of academic circles so that modern Russian prose can become a mass product, and not just a treasure of Chinese Russian scholars. Leo L?wenthal (1900-1993) is known as a critical theorist, a literary and communication theorist with an academic reputation in Europe, dedicated his life to applying the critical theory of the Frankfurt School to the analysis and research of literary and social problems. [?] This article contains all the data from the largest Internet source for finding dissertations "Zhi Wang" ())))))? ( ( (cnki.net ), the largest Internet source for searching for academic resources "Tu Xiu" (), (duxiu.com ) and the Chinese largest website about books and the social network of book readers "Douban" () (douban.com )

References

1. Zhao Xue. (2019) L. Ulitskaya in Chinese Russian Studies: reasons for popularity, aspects of study. Philology and Man, ¹1. 155-163. Retrieved from https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=37146381

2. Zhao Xue, Govorukhina Yu.A. (2020) The study of modern Russian women's prose in Chinese Russian studies. Siberian Philological Journal, ¹3.142-155. Retrieved from https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=43948999

3. Zou Lu wei, Mikhailova M.V. (2019) Perception of A. A. Akhmatova and her creativity in China. Bulletin of the Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Series: Literary Studies, Journalism, 24(2). 223-234. Retrieved from https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=40102738

4. Ruge Jing, Monisova I.V. (2020) The state of research of modern Russian prose in China. Bulletin of the Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Series: Literary Studies. Journalism, 25(2). 277-286. Retrieved from https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=43799917

5. Leo Lowenthal. (1961) Literature, Popular Culture and Society. Englewood Cliffs: NJ Publication.

6. 汪介之.(2017) 文学接受的不同文化模式——以俄罗斯文学在中国的接受为例[Wang Jiezhi. Various cultural models of the perception of literature — on the example of the perception of Russian literature in China]. Jiangxi Academy of Social Sciences. 37(11), 82-87.

7. 刘文飞.(2015) 刘文飞谈俄国文学翻译:我从来没有悲观过[Liu Wenfei. Liu Wenfei talks about Russian literary translation: I have never been a pessimist]. The Beijing News, 2015-10-31,Retrieved from: http://epaper.bjnews.com.cn/html/2015-10/31/content_605278.htm

8. 张建华. (1995) 论俄罗斯小说转型期的美学特征[Zhang Jianhua. On the aesthetic features of the transition period in the development of Russian novels]. Journal Modern Foreign Literature, 12, 88-95.

9. 张捷.(2003) 俄罗斯的女侦探小说家群体[Zheng Jie. A group of women writers of Russian detective prose].Dynamics of foreign literature, 6, 26-29.

10. 李建军. (2019) 对俄罗斯文学传统的完美接续——阿列克谢耶维奇的巨型人道主义叙事[Li Jianjun. A wonderful continuation of the Russian literary tradition — a giant humanitarian narrative Alexievich]. Modern Literary Tribune, 3, 4-15.

11. 张变革. (2016) 以情感唤醒理性:阿列克谢耶维奇创作中的知识分子话语[Zhang Biange. Awaken the mind with the help of emotions:Intellectual discourse in the works of Alexievich]. Russian Literature and Art, 2,17-24.

12. 刘文飞.(2017) 祖列依哈的世界[Liu Wenfei. World of Zuleikha]. Journal "Literature and Art", 2017-3-13,Retrieved from http://www.chinawriter.com.cn/n1/2017/0313/c405175-29140531.html

13. 王树福. (2014)《带花的十字架》仿真与幻想[Wang Shufu. From simulation to fantasy "A"]. In: Yan Jingming (Eds.), Passion and dreams in the literary world(pp.356-361). China,Hefei: Publishing House of Anhui Literature and Art.

14. 王宁. (2019) 当代中国外国文学批评史 [Wang Ning. The history of modern Chinese criticism of foreign literature]. China, Beijing: Publishing House "Social Science of China".

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

Russian Russian literature The subject of the study in the article "The spread of modern Russian women's prose in China of the XXI century from the point of view of literary communication" is the popularity among Chinese readers and researchers of the work of modern Russian writers. The author identifies two waves of interest in Russian women's prose in China: the first opened to the Chinese reader L. S. Petrushevskaya, L. E. Ulitskaya, T. N. Tolstoy, V. S. Tokarev, A. Marinin, D. Dontsov, the second – O. Slavnikov, E. Chizhov, S. Alexievich, G. Yakhin, D. Rubin, E. Alexandrov-Zorin, E. Kolyadin, M. Stepanov. The author concludes that the leading role in popularizing Russian women's prose of the first wave was played by Russian scientists, but now there is a tendency to perceive the type of literature under study as an object of interest to the mass reader and, accordingly, the publisher. The structure of the article is successful, the language is predominantly scientific (although there are phrases in the text with excessive evaluation and expression for the scientific style, for example: "In translations, the professional literary experience of Chinese Russian scholars and their knowledge of the Russian language helps to preserve the artistic charm of the original text"), the statistics and graphs provided increase the credibility of the study. The topic of the study is extremely relevant in the context of the growing interest in Russian-Chinese cultural and literary ties. The disadvantages of the article include the following: Russian Russian literature: 1) the concept of "literary communication" is insufficiently disclosed and related to the content, the need to include it in the title is questionable; 2) conclusions are not always justified: for example, based on a comparison of the number of translations of Russian women's prose and scientific works devoted to these translations, the author writes: "The more Chinese Russian scholars pay attention to the works of Russian writers, the more attention the student audience pays to their works and the more translations of the corresponding works", but does not indicate why the connection, in his opinion, cannot be reversed – the more translations, the more research; 3) graphs are not explained, for example, the author gives numerical values, but does not indicate in which units the "attention of the Chinese audience to the writer" is measured; 4) there are too general and unclear phrases with missing logical links, for example: Russian Russian women's prose is moving from the previous stage to the next — the recognition of Russian women writers by the Chinese audience is no coincidence"; 5) the comparison of "the majority of readers", "professional readers" and "readers" in the fragment seems unsuccessful and diverse: "What do Chinese readers expect from Russian women's Prose? For most non-professional readers, the appeal of Russian women's prose, like any kind of foreign literature, lies in an alternative perspective for learning about the world and China. For professional readers, these are new opportunities to expand knowledge about the Russian language and culture. Russian Russian women's prose provides a channel for Chinese readers to express themselves and reflect on what Russian women writers have written about the relationship between the sexes." In the last quote, it is also unclear how Russian prose can help the Chinese in understanding China; probably, Russia was meant here by a typo. In general, the article is of interest and can be recommended for publication after editorial revision. Comments of the editor-in-chief dated 06/27/2022: "The author has fully taken into account the comments of the reviewers and corrected the article. The revised article is recommended for publication"

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|