|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-7144.2022.12.39310

EDN: XHQBIW

Received:

04-12-2022

Published:

30-12-2022

Abstract:

The article is based on the results of questioning and interviewing representatives of the first, one and a half and second generations of migrants in the Lipetsk region. On the basis of praxeological and transnational approaches, the family memory of migrants was considered as a configuration of relevant narratives and practices that simultaneously take into account the historical cultures of the country of origin and the host society. Family commemorations play an important role in the construction of the identity of migrant communities in the Russian provinces. The study revealed the persistence of the factor of family and compatriot relations as the main reason for choosing the place of resettlement. Analysis of the results of the survey and interviewing indicates a high level of openness of the first, one and a half and second generations of migrants in relation to the Russian language and secular holidays in Russia. At the same time, migrants continue to consider the religious holidays of the country of origin and belonging to the diaspora as markers of their identity. The study showed that migrants continue to actively oppose the images of the host society and the country of origin, which indicates the coexistence of communities of memory of local residents and migrants as "parallel" to each other. Significant differences between the generations of migrants in assessing the change in lifestyle after migration, in the level of involvement in the religious traditions of the country of origin, in the subject of nostalgia were revealed.

Keywords:

family memory of migrants, intergenerational dynamics, transnationalism, historical culture, communicative memory, cultural memory, memory communities, commemorative practices, integration of migrants, praxeological approach

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

The article was prepared with the financial support of the RNF grant, project No. 22-28-00503 "Transformation of the collective memory of migration communities in modern Russia: intergenerational dynamics, family values and commemorative practices"Cultural integration of migrants continues to be an urgent task not only for developing countries, but also for developed countries of the world. At the same time, if the countries of the European Union and North America have more than half a century of experience in this matter, then Russia has yet to develop a system mechanism of integration adequate to our cultural specifics and at the same time [1]. In this article, by migrants we mean only external migrants (immigrants), leaving aside the issues of integration of internal migrants. Researchers working with issues of cultural integration of migrants cannot fail to take into account aspects of cultural memory, which, in comparison with issues of citizenship, language and education, at first glance, do not have such decisive importance. This thesis could be recognized as fair only if we were talking about one generation of migrant workers. However, the experience of foreign countries convincingly shows that the successes and failures of integration policy at the level of commemorative practices are noticeable in the conditions of several generations of migrants, where their family memory begins to play a special role [2, 3, 4, 5]. In turn, it would be wrong to see in the family memory of migrants, something static and unchangeable. Global migration processes are destroying the previously unshakable cultural and national framework for the existence of family memory, making it part of the cross-border space and intercultural exchange. Modern Internet communications have fundamentally changed the nature and specifics of the transmission of family historical experience, which turns out to be public. Accordingly, the transformation of family memory turns out to be a consequence of the extreme dynamism of the commemorative space itself and the emergence of new practices of memories, mnemonic communities and actors presenting new issues relevant to family memory for the modern world. Another significant challenge for the family memory of migrants is the intergenerational dynamics itself, which is confirmed by foreign studies [6, 7, 8]. How does intergenerational dynamics influence the transformation of migrants' family memory in modern Russia? We analyzed this issue on the example of the Lipetsk region, a typical Russian region of Central Russia with an agro–industrial and industrial orientation, a homogeneous ethnic composition (96.3% Russian), and also characterized by a low level of political competition [30]. Accordingly, the purpose of the article is to analyze the intergenerational continuity of knowledge, values and practices of family memory of external migrants in the selected Russian region. Despite the fact that research on the cultural integration of migrants in Russia is actively conducted today in the domestic research environment [9, 10, 11, 12], The issues of migrants' family memory in the light of intergenerational dynamics have only been touched upon to a relative extent in recent studies [13, 14]. A few years ago, within the framework of the research project "Cultural Memory of Russia in the situation of global migration challenges: conflicts of representations, risks of oblivion, transformation strategies", supported by the Russian Science Foundation (2017-2020), we proposed several theses relevant to the topic of this article. The results of the study indicate the possibility of cultural diffusion of the host society and migrants in Russia at the level of cognitive, linguistic, behavioral and value aspects. At the same time, the revealed level of openness of migrants and the host society in Russia rather speaks of the neutrality and secondary nature of this sphere in comparison, for example, with socio-economic competition and inequality. Both the host society and migrants are currently striving to reproduce "parallel" memory communities, where one side has virtually no influence on the other, and the second cannot point to its important place in the practices of constructing a new Russian identity, which is partly explained by the low level of awareness of migrants of their interests in Russia. It is concluded that the further development of the current situation will contribute to the growth of conflict potential due to the fact that the "second generation" of migrants has not yet entered into active life in Russia. In comparison with the foreign context, the Russian version demonstrates to a greater extent the predominance of implicit forms of conflict at the level of cultural memory. If studies abroad point to status conflicts to a greater extent, then in Russian conditions the memory of migrants turns out to be one of the tools of their self-defense, thereby projecting the dominance of protective memory conflicts. If in Western Europe and the USA the relationship between the host society and migrants often acquires the character of a clash of the values of modernism and postmodernism with the traditional culture of migrants, then in Russia we rather have to talk about a clash of various variants of traditionalism, characteristic of both the old-time population and external migrants [15, 31]. The next step was taken by us within the framework of the project "Transformation of the collective memory of migration Communities in Modern Russia: intergenerational dynamics, family values and commemorative practices", supported by the Russian Scientific Foundation for 2022-2023. One of the objectives of the project was to conduct a series of sociological studies in 2022 on the territory of the Lipetsk, Saratov, Sverdlovsk and Kemerovo regions, as well as the Republic of Tatarstan. The objective of this study was to identify and compare the level of knowledge about the family past, the interpretation of the events of the family past in the context of the narratives of representatives of different generations of migrants within the same family. Another important task of the research was to identify the most relevant practices and channels for broadcasting family memory of different generations of migrants. The study was conducted using qualitative (narrative interview) and quantitative (questionnaire) methods. The article presents the results of a face-to-face survey of 300 migrants permanently residing in the Lipetsk region. Quota sampling (multi-stage). The quotas are the gender and age of the respondent, as well as belonging to different generations of migrants. The study was conducted in 2022. To analyze the results, the frequency distribution of responses and conjugacy tables (generational analysis) were used. To conduct the survey, we identified representatives of the first generation or generation "1" (came from his native country over the age of 18), one and a half generation, which included generation "1.25" (arrived at the age of 13-17 years), generation "1.5" (arrived at the age of 6-12 years) and generation "1.75" (arrived at preschool age), as well as the second generation or generation "2" (born in Russia).

As part of our research in the Lipetsk region in the spring of 2022, we also interviewed 35 people (14 families) with a migration background. Due to the specifics of the migration environment in Russia, represented primarily by immigrants from the former CIS countries (Central Asia and Transcaucasia), we interviewed two-generational families. Qualitative research was conducted by the method of narrative interview based on the methodology of the biographical interview of Fritz Schutze (6 steps) [16, 17]. As you know, Fritz Schutze suggests considering a biographical story recorded during a narrative interview as a conceptually unified process that simultaneously unfolds against the background of the manifestation of the entire semantic structure of the biography. In this case, the interviewer does not interrupt the narrator, allowing him to build the plot of the story in a free form. Only at the end of the interview, the narrators are asked to answer a number of clarifying questions, which in the language of Schutze's theory has been called the "phase of narrative questions" [16, s.80]. According to F. Schutze's life story is a sequentially ordered layering of large and small sequentially ordered procedural structures. With the change of dominant procedural structures, the corresponding general interpretation of the life story by the biography carrier also changes over time. The most important goal of the methodology of F. Schutze is the correlation of the informant's life story with his subjective interpretations. This is achieved through the comparison of such procedural structures as intentional processes (the life goals of the biography bearer, the actions taken by him in the process of overcoming difficult life situations), institutional patterns (prescribed rules of behavior on the part of the family, educational system, professional circle) and flow curves (the dynamics of identity in general). Commenting on the ideas of F. Schutze, E.Y. Rozhdestvenskaya notes that the curves of the current in the biographical analysis of F. Schutze can have a positive (ascending in progression, by establishing new social positions, they open up new spatial possibilities for the actions and development of the personality of the biography carrier) and a negative (descending in progression, they limit the space of possible actions and development of the biography carrier during a special layering of action conditions that cannot be controlled by the biography carrier himself) meaning. He emphasizes that "the identity of the biographer does not coincide in rhythm with the procedural structures of the course of life, since the search, giving meaning to the biography become possible as life positions change, situations are pushed into the past, and a time distance is formed to them" [17, p.114]. Thus, in the situation of biography, the narrating Self represents its past, that is, the narrated Self, acting as a remembered carrier of actions. The conceptual framework of our work is a transnational approach, the methodological significance of which lies in the emphasis on the creation of social fields by migrant communities that cross geographical, cultural and political borders [18, 19, 20, 21]. We are talking about a social field created by migrants and including at the same time the socio-cultural practices of both the host society and the country of origin. Modern studies emphasize that "migrants become transmigrants when they develop and maintain multiple family, economic, social, organizational, religious and political relations that cross state borders, and their public identities are formed in interaction with more than one national state. In the host society, they are not temporary residents, because they settled and began to be incorporated into the economy and political institutions, localities and patterns of everyday life of the country where they live at the moment. However, at the same time, they maintain ties, build institutions, manage transactions and influence local and national events in the countries from which they emigrated" [22, p.15]. No less important for us is the fact that it is the family (more often extended) that turns out to be the main transnational unit [23]. The research emphasizes that "transnational families are understood as such families whose members are separated and live in different states, often for quite a long time, but despite this they maintain contacts and create a sense of family unity, community and emotional involvement" [22, p.20]. In the Russian case, this is usually associated with the residence of older relatives in the countries of origin, while their children and grandchildren live, work and study in Russia. Praxiological understanding of family memoryIn one of the most notable studies of recent years, family memory (family-generic memory) is interpreted as "a program of perception, reproduction, preservation and transmission of social heritage that has developed in the human mind as a representative of the most complex social system of kinship – a property that is the basic matrix in relation to all other social relations. Memory "colors" them with feelings, mythologizes and transforms, is transmitted to descendants in the form of family stories, legends. In subsequent generations, this is fixed in the peculiarity of the mental characteristics of the community" [24, p.18]. Agreeing with this definition, it can be argued that family memory is, first of all, a certain system of knowledge, beliefs, mythologies and legends about the family's past, as well as about historical events reflected in it. However, family memory is also a set of practices for reproducing family experience, which may or may not be reflected. It is the practical, everyday side of the reproduction of family relations that prevails over its other elements. L.Y. Logunova notes: "the space of kinship determines the specifics of the structure of family-generic memory, the eventfulness of life situations is fixed by family-generic memory depending on the social positions of the related group, the invariance of private practices and life strategies in different historical and settlement situations" [24, p.31]. The post-metaphysical understanding of the social actualized the idea of practices as the environment in which social interaction and the construction of social order take place [25]. The application of the ideas of a "practical turn" in the research of collective memory (memory studies) has long shown its fruitfulness. It is the idea of practices as a social reproduction environment that has had a stimulating effect on the growth of collective memory research, the volume of fundamental and applied research of which allows researchers to talk about memory studies as a special interdisciplinary field of scientific knowledge. In this regard, the study of the practical component of the transmission of family traditions and values is more promising than the study of a simple level of awareness about the history of the country of origin and information about the family past. In other words, the history of the country of origin and knowledge about the family past are actualized in the context of the very practices of interaction between generations of migrants.

The subject nature of the activity allows us to consider family memory not only as a set of knowledge on family history, but also as a set of habits characteristic of the sphere of work, life and leisure in the family [26]. The praxiological approach to family memory shows that a particular person addresses family memory through the prism of his autobiographical memory and its crises. The personality turns out to be the selector who, each time from the perspective of the present, decides which part of the family memory to actualize and which to leave in the shade. This thesis can be successfully illustrated by the example of the concept of "post-memory" by Marianne Hirsch, who in her book convincingly shows the transformation of family memory of the Holocaust in an intergenerational perspective [27]. Understanding activity as a system allows us to pay special attention to the very practices of coordinating various ways of thematizing the family past, to the very complex of relationships between the main components of family memory, represented not only by family narratives and artifacts, but also by everyday traditions of work, life and leisure. Thus, family memory in such a case turns out to be a mechanism of linguistic transformation of the practices of family historical experience, it transforms historical experience into a narrative. Moreover, family memory contributes to the transformation of communication into communication, that is, communication takes the form of emotional involvement in the process of such an exchange and intentional experience of the past. However, it would be wrong to believe that family memory and its practices of translating historical experience exist as something closed within the family. Astrid Erl, a German researcher, quite rightly believes that "versions of the family past are created collectively, " the unity of family memory is based not so much on the continuity of the stories that are told, but more on the continuity of opportunities for acts of participation in the process of remembering. Family memory, therefore, is a dynamic and contextual construct that can vary significantly over time, as well as due to different groups and audiences" [28, p.313]. In our recent study of the features of the everyday mythology of family memory in the modern Russian province, we sought to show family memory as a dynamic field of meanings and practices of family historical experience, located between the autobiographical memory of an individual and historical culture [26, p. 219]. A successful definition of historical culture is found in the work of the English historian David Wolf. He believes that "historical culture consists of habitual ways of thinking, languages and means of communication, models of social harmony, which include elitist and popular, narrative and non-narrative types of discourse <...> Moreover, ideas about the past in any historical culture are <...> part of the mental and verbal background of that society, which uses them, putting them into circulation among contemporaries through oral speech, writing and other means of communication. This movement and the process of exchanging elements of historical culture can be conveniently called its social circulation" [29, p.9-10]. Our point of view is that historical culture is not just an intermediary, but an active environment that interacts between different types of knowledge about the past and forms of memory of communities, as well as their inherent value bases in relation to the past. In this case, family memory turns out to be simultaneously one of the media of this circulation, but at the same time it is influenced by this circulation of images of the past, placing family memories in new interpretive contexts. Culture of the host society in family memory of migrants Domestic demographers and sociologists have repeatedly noted the fact that the bulk of non-ethnic and external migrants in Russia are still associated with immigrants from the former Soviet republics (Transcaucasia, Central Asia) [1, 10, 11]. Taking into account this circumstance, in our study we tried to take into account several generations of migrants at once, whose parents or older relatives could have been in our country back in the Soviet years. Accordingly, we compared the responses of representatives of the first, one and a half and second generations, the differences between which we have outlined above. A number of questionnaire questions were designed to analyze the age and educational characteristics of migrants. The survey showed that two-thirds of our respondents came to Russia after coming of age and thus belong to the first generation. At the same time, within this generation "1", the predominance of the age group 30-39 years (32%) was revealed. It is also significant that representatives of age cohorts from 40 years and older made up a total of 41% of respondents. These figures seem quite understandable, given the dominance of labor immigration in Russia. In this regard, V.S. Malakhov's conclusion that "the "second generation" of migrants has not yet entered into active life in Russia <...> If the first generation of migrants, as a rule, is aimed at adapting to the conditions of the host country (and therefore prefers to behave as conformally as possible), then their children do not they are prone to such a degree of conformity" [1, p.13]. Respondents were also asked about the length of residence in the region. It was revealed that almost a third of the respondents live in the Lipetsk region from 6 to 10 years. Almost a fifth of respondents (18.2%) stated that they have been living in the Lipetsk region for 3 to 5 years. The same was the number of those who lived in the region from 11 to 20 years. The trends of the predominance of labor migration in Russia and the desire of migrants to return to their small homeland are especially noticeable due to the number of those who have lived in Russia for more than 21 years (13.6%), as well as those who were born in our country (4.5%). Interesting were the results of studying the educational level of visitors, where the number of those who had higher education was noticeable (36.3%). At the same time, 4.5% of the respondents from this number were representatives of the "2" generation, that is, they were born in Russia, and a high percentage of higher education among newcomers can presumably be associated with their higher education in Russia. The figures of the answers to the question about the level of education show that in most cases migrants coming to Russia have either incomplete secondary or secondary vocational education (27.2%). This correlates with the recent research of our colleagues [11]. It is also significant that of the 13.6% of respondents who indicated that they had a full secondary education, 9% were born or spent most of their lives in Russia (generations "1.75" and "2").

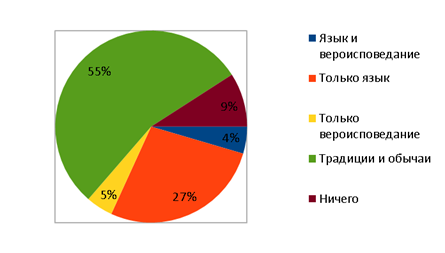

The first set of questions in the questionnaire was related to the issues of comprehension of moving to Russia and attitude to the cultural traditions of the host society. The factor of family and community relations continues to be the most important in the context of understanding the reasons for choosing a place of emigration. So, answering the question about the reasons for choosing the Lipetsk region and the city of Lipetsk, 72.7% of respondents indicated that relatives and fellow countrymen lived in this region. It is also significant that for 9% of respondents, the choice of place of residence was random. The study revealed a fairly high level of openness of migrants towards certain aspects of the cultural memory of the host society in Russia. In particular, the respondents' answers to the question "What are you ready to adopt (have already adopted) from Russian culture into the daily life of your family?" revealed a willingness to adopt secular traditions and customs of Russia (54.5%), as well as the language (27.3%). At the same time, the religious aspect of interaction with representatives of the host society revealed the unwillingness of a significant part of migrants to positively relate to the change of religion of children and immediate relatives (Figure 1). It is significant that only 4.5% of respondents in generation "2" indicated the possibility of adopting the religion of the host society.

Diagram 1. Results of answers to the question "What are you ready to adopt (have already adopted) from Russian culture into the daily life of your family?" An important marker of the attitude to the cultural memory of the host society is the use of its language in the family, as well as openness towards local holidays. As the experience of foreign studies shows, even those immigrant groups that could be called deeply integrated, as a rule, use either their native language in the family, or equally use both their native language and the language of the host society [7, 8]. In our case, a fairly high level of the use of the Russian language in family life was also recorded. Russian Russian is a native language for 27.3% of our respondents (50.1%) noted that they try to intentionally use Russian at home, and for 27.3%, Russian is generally their native language. It was quite expected to see that almost a quarter of respondents (22.7%) use Russian when they lack words of their native language. The respondents were also asked about the attitude of their families to the religious and secular holidays of the host society. Comparing the answers with the results of our recent study [32], we can talk about a relative improvement in the situation in the field of openness of migrant communities to the festive culture of the host society in Russia. The results of our previous study showed that migrants in Russia generally have a positive opinion of Russian secular and religious holidays, but only a third of them said they were ready to take an active part in them (especially migrants over 50 from CIS countries). We also found that with age and an increase in the length of residence, migrants find more opportunities to celebrate religious holidays [32]. In the current study, answering the question "How does your family feel about local holidays?", almost two-thirds of respondents (72.7%) indicated that they accept and celebrate not only secular, but also religious local holidays. At the same time, this area continues to be quite closed for the festive culture of the host society. This is evidenced by the responses of those who indicated only secular holidays (18.2%), as well as a fairly high percentage of those who do not share local holidays at all (9.1%). The results of the answer to this question in the intergenerational aspect show that the most open local holidays were representatives of generation "1" who came to Russia in adulthood and representatives of generation "2" born in Russia. These results were expected due to the presence of memory of Soviet cultural practices in the first case and a greater degree of integration into the host society in the second. At the same time, the share of those in generation "1" accepts and celebrates only secular holidays in Russia in the family also remains high (18.2%). Despite the fact that family memory is primarily associated with ideas about family history, historical events are an important framework for family commemorations. In this regard, we asked respondents which of the listed events of the recent Russian past had the greatest impact on their family. And here the answers visibly revealed deep differences between the generations of those who came to Russia in childhood and adolescence, those who were born and study in our country, as well as between the older generation who witnessed the historical events of the last thirty years. It is quite expected that for generation "1" the most significant event was the collapse of the USSR in 1991. This option was chosen by a third of respondents (31.8%). The second most important event for this generation was the currency crisis of 2014-2015 (13.6%). A little less sensitive for the families of our respondents was the coming to power of Mikhail Gorbachev and the beginning of Perestroika (9.1%). At the same time, almost 14% of respondents indicated that they did not find a single crisis in Russia, because they arrived later. The answers of the representatives of the "1.25" generation who came to Russia at the age of 13-17 turned out to be different. According to the estimates of this age group (unexpectedly for us), the most noticeable impact on their families was the August coup of August 18-21, 1991, as well as the expected currency crisis in Russia in 2014-2015. A similar situation has developed in the generation "1.5", whose representatives came to Russia at the age of 6-12 years. The unexpected relevance of the August coup in these two generations, in our opinion, is explained to a greater extent by the influence of the education system. where this historical event is given a great place in the modern history of Russia. At the same time, for representatives of the "1.75" and "2" generations, the events of the collapse of the USSR turned out to be the most significant, as well as for older relatives. In this case, this can be explained not only by involvement in the Russian education system, but also by family comments, where the opinions and assessments of older relatives can largely determine the assessments of younger generations.

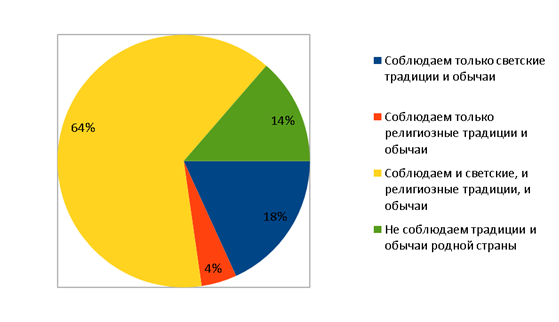

Since family memory is not only knowledge about the family past, but also the practical context of the transfer of family heritage, one of the questions in our questionnaire was devoted to the respondents' ability to compare the lifestyle of the family in the country of origin and after moving to Russia. The answers of the representatives of generation "1" were of the greatest interest to us, because, having experience of long-term residence in the country of exodus, they could really state the presence of changes in lifestyle. Processing of the survey results of this age group showed that only 13.8% of respondents are ready to say that their lifestyle has not changed. Almost a fifth of respondents in this generation noted that the lifestyle has not changed much (18%). The same number of respondents stated that the lifestyle is different, but not significantly (18.2%). Thus, even though more than a quarter of the representatives of this generation indicated that their lifestyle has changed significantly (27.3%), the results of the survey show that almost half of the respondents have practically not changed their lifestyle. Comparing the answers of generation "1" with generations "1.25" and "1.5", we saw that the vast majority of respondents in these generations who came to Russia in childhood and adolescence, on the contrary, pointed to a noticeable contrast between the lifestyle in the country of origin and in Russia. It is significant in this case that representatives of two more generations who came to Russia at preschool age (generation "1.75") or were born in our country at all (generation "2") were unanimous, noting that the lifestyle is very different. The current situation is absolutely understandable in the light of similar trends abroad, where we also see a significant integration of the one and a half and second generations of migrants into the daily practices of the host society [6, 7, 8]. Interviewing helped us to better understand the specifics of intergenerational differences in the perception of cultural practices of the host society. The results of a comparative analysis of interviews with six two-generational families revealed an unambiguous dominance of ascending narrative curves, when migration experience turned out to be an important factor in the further family dynamics of informants. Application of F. 's methodology Schutze, when we considered family history as a kind of collective biography of the family, showed that the interpretative efforts made by informants to present family history, in most cases, coincided with the biographical processes of the narrators and their older relatives. The key event for the absolute majority of families was moving to Russia. Intentional processes implemented by the family as a subject of commemoration made it possible to overcome institutional constraints, which allowed us to see family biographies as an ascending process. At the same time, in the case of representatives of the first generation, nostalgia for the country of exodus turned out to be a significant factor, which acquired features of both general nostalgia for the USSR and nostalgia for the lifestyle in general. "Moving to another country was very difficult for us <...> not in terms of documents, but in terms of changing society entirely. An Asian country, it treats the adult generation, the generation of grandparents more respectfully. Everything connected with this here in Russia is very visible <...> for example, on the bus, young people in no way show respect for pregnant and elderly people" (Dmitry, 42 years old). Representatives of the one-and-a-half generation also demonstrated nostalgia, but it turned out to be associated not so much with the country of exodus as a whole, as with individual things, practices or memorable places. An important point that we identified in the interviews of the first and one and a half generations of migrants is the preservation of the opposition of their family to the host society ("we are them", "we have you", "our traditions are your traditions"). Among the representatives of the second generation, this trend was less noticeable, since Russia was perceived as a place of birth, and the informants themselves spoke of themselves as citizens of Russia. At the same time, all generations have demonstrated a tendency to combine the holidays of the country of origin and the host society. However, if the first generation actively declared their commitment to the religious holidays of the country of origin and the secular ones of the host country, then in the case of the one and a half and the second generation, the indistinguishability of secular and religious holidays was recorded, as well as a high level of participation in secular holidays in Russia. "I am an Azerbaijani and I have a traditional upbringing, which is peculiar to my people, but more democratic. We go with time. My family is quite religious, but I am not like that myself <...> We have all read the Quran, but we are not fanatics, we are more modern" (Amil, 19 years old). Features of the translation of migrants' family memory in an intergenerational perspectiveThe situation in the host society and the attitude of migrants towards it are an important, but by no means the only factor influencing the specifics of the commemorative practices of migrant communities. No less important are the features of the translation of family memory itself in an intergenerational perspective. In an effort to understand the peculiarities of this broadcast, in the second block we asked our respondents questions about the relevance of the traditions and customs of the country of origin, emotional attitude to former life, interest in family narratives and the peculiarities of the transmission and storage of family heirlooms. The survey revealed a high level of preservation of traditions and customs in family life among our respondents. Thus, more than half of the respondents (64%) indicated that they observe both secular and religious traditions of the country of origin in their family life. At the same time, the share of those who observe only secular traditions turned out to be quite noticeable (18.2%) and the share of those who observe only religious traditions (4%) turned out to be almost invisible. In this case, it should be noted that migrants themselves hardly draw a clear demarcation line between secular and religious traditions and customs. This is confirmed by the results of the interview, when it was often difficult for our respondents to label traditions as secular or religious. In the respondents' answers to this question, the growing trend of a negative attitude towards the traditions and customs of the country of origin was quite visibly manifested. Thus, 14% of the surveyed migrants in the Lipetsk region generally stated that they do not observe these traditions (Figure 2).

Diagram 2. Results of the answers to the question

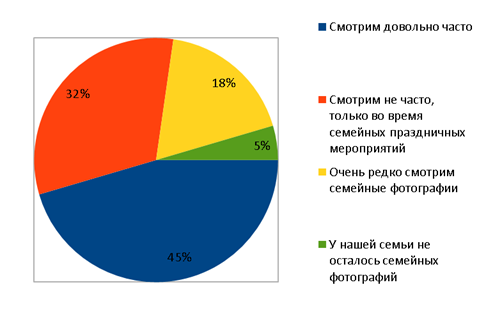

"Do you observe the traditions and customs of your native country in your family?" It was quite easy to explain such a significant number of negative responses after referring to the specifics of the responses in the framework of a comparative analysis of generations. A detailed analysis of the responses applied to different generations showed that two-thirds of respondents who answered negatively were people of the one and a half and second generation (12% of 14% of respondents). This situation is fully explicable in the light of international experience. For example, Josephine Raash in her research shows that migrant children in Berlin often do not seek to form a historical consciousness reflecting their diasporic or hybrid identity. She notes that they identify themselves situationally, choosing different pages of the international past as significant dates and events [6, p.82]. The example of different generations of Bosnian migrants in Denmark, who became the object of scientific interest of Sanda Ullen, a researcher from the University of Vienna, is also indicative. Taking as an object of research one family and its regular visits to Bosnia, Sanda Ullen analyzed the perceptions and memories of different generations of Bosnian refugees in relation to their homes and places of memory in the country of exodus. It was revealed that if for older generations of family members visiting the house was a reminder of pre-war times and a return to the past, then for young Bosniaks this place was presented as a recreation space and a meeting area with older relatives [7, p.94]. The results of a comparative analysis of interviews of several generations of migrants in the Lipetsk region allowed a deeper understanding of the peculiarities of different attitudes to the traditions of the country of origin. In interviews with representatives of the first generation, we identified tendencies to consider the preservation of traditions as a moral duty, avoiding attempts to critically assess the cultural heritage of the country of origin, as well as the desire to talk about traditions and customs on behalf of the people. In contrast, representatives of the second generation demonstrated a more personal view, accepting some traditions and disagreeing with others. Another trend was visibly positioning himself in the story as a citizen of Russia. We also asked a question about the respondents' emotional attitude to memories of life in the country of exodus. The answers to the question revealed the expected unanimity, not only among those who came to Russia after the age of 18, but also, significantly, among those who were born in Russia. As we expected, more than 91% of respondents noted that they remember life in the country of exodus with good feelings. The unanimity of different generations here is explained by the influence of older generations on younger ones in their assessments of the country of origin and its traditions, which is common to any family memory [26]. Another fact is indicative. The remaining 9%, who indicated the neutrality of memories of the country of exodus, were almost equally distributed only between two generations – the first generation (4.2%) and the second generation (4.8%). In the first case, the reason may be related to disappointment with life in the country of exodus, while in the second case it may be about indifference due to the fact that young people have simply never been to their historical homeland and, due to their social circle in Russia, do not feel any emotional attachment to it. This situation was recorded by us during the interviewing of two families, where young people openly declared their indifference to the country of origin of their parents, considering Russia as their full-fledged Homeland. "And I was born myself already in Chaplygin. So I have never been to Armenia like my older and younger sisters. We were born and raised in Russia. They also studied at the Chaplygin school. Now we live in Lipetsk, we are finishing the 1st course <...> I have never been to the Homeland of my ancestors. And there is no need to go, in particular, I am not interested. My father tells me a lot about what's there and how. That is, I have some idea. How things are there. There is no burden to go. Nothing pulls me there. My great-grandmother and great-grandfather live there and a number of other relatives, but somehow I don't want to go there yet" (Ararat, 18 years old). It would not be an exaggeration to say that one of the most important sources of family continuity is photography, the role of which in the construction of family memory has already been written a lot of works in Russia and abroad [27, 33]. In this regard, our respondents were asked questions about the attitude to family heirlooms, the frequency of viewing and the features of storing family photos. The task of the first question was a general analysis of the attitude of representatives of several generations of migrants to the practices of transferring family heirlooms. The answers to this question testified to the expected high level of value of family heirlooms in the minds of respondents. None of the interviewees revealed a willingness to transfer the relics to the national museum or a desire to part with family values. 77% of respondents indicated the need for further transfer of relics to the next generation in the family, and the absolute majority of such responses were revealed in all generations except the first (generation "1,25", "1,5", "1,75", "2"). Despite the fact that among the representatives of the first generation, almost 60% of respondents also indicated the need to transfer family heritage, yet 22.7% found it difficult to answer this question. This is explained either by the absence of family heirlooms themselves, due to relocation or any critical social events in the country of origin, or by the secondary nature of the very problem of memorials for migrant workers in Russia, who are not always in acceptable conditions for a full life in the host Russian society [1]. Another question related to the frequency of viewing family photos, indicating the important role of continuity itself in the family. The respondents' responses revealed the generally important role of family photo sharing practices (Figure 3). Slightly less than half of all respondents (45.5%) said that they look at photos quite often. It was also quite expected to see that a third of respondents (31.8%) look at photos only on holidays, which is generally typical for Russians. The survey showed that almost 20% of respondents very rarely look at photos and 4.5% indicated the fact that there are no family photos as such.

Diagram 3. Results of answers to the question "How often do you look at family photo albums?"

An analysis of the answers to this question in an intergenerational perspective showed a gradual decrease in the frequency of viewing as we move towards the second generation. If among the representatives of the first generation, a little more than a third of respondents reported a high level of frequency of viewing family photos, and in the generation of "1.25" the absolute majority, then among the representatives of generations "1,5", "1,75", "2" we didn't find any answers in this variant. At the same time, if representatives of the one-and-a-half generation in most cases indicated periodic viewing of family photos on holidays, then already in the second generation the number of those who periodically look at photos with relatives and those who look at them extremely rarely equaled. Another indicator indicating the value and significance of images of the family past in an intergenerational perspective is the practice of storing family heirlooms. One of the questionnaire questions in this regard was devoted to how our respondents prefer to store family photos. Analyzing the answers to this question, we understood that the modern influence of digital culture and its media makes quite understandable changes in the practices of storing and reproducing family memory [34]. The results of the survey showed a fairly uniform distribution of responses according to various options, reflecting a greater or lesser level of openness to modern digital technologies. Almost 41% of respondents indicated that they keep albums wherever they print photos. Slightly more than a quarter of respondents (27.3%) noted that photos are not printed, but stored on special digital media. And another third of respondents (31.8%) said that they keep photos in their phone and are not going to print them out specifically. As we expected, the largest percentage of those who indicated the fact of keeping family albums was revealed among the representatives of the first generation, which is primarily due, in our opinion, to the distrust of older generations of digital media. At the same time, even among the representatives of the first generation, the percentage of those who use digital media or even store photos in the phone turned out to be almost equal to the number of those who use only special albums for printed photos. This is not surprising, taking into account the transformation of modern photography and the dominance of digital media in modern historical culture. It was also quite expected to see the complete lack of interest of representatives of the one and a half and second generations in the practices of storing printed photos, as well as the dominance of openness to digital media in their responses. In this matter, there are significant differences between representatives of generations "1,25", "1,5", "1,75", "2" we did not see it, because the answers indicating the storage of photos in the phone were evenly distributed among the representatives of the listed generations. The conclusion of the second block was the question about the respondents' interest in the narratives of older generations dedicated to the family's past. The task of this question was to identify the level of readiness to adopt family historical experience. Despite our skeptical expectations, this question revealed an amazing unanimity of respondents, where almost 96% of respondents among representatives of all generations stated an unequivocal interest in the family memories of older relatives. It is significant that only 5% of respondents and only among the first generation of migrants found it difficult to answer this question. Such unanimity clearly indicates that family and family memory continue to be the most important area of the daily life of migrants in Russian society, regardless of the depth of family historical narratives, as well as the abundance of family heirlooms. Moreover, it is also necessary to take into account the fact that not every family is able to take with them a large number of family heirlooms from the country of origin, which makes the narratives of older relatives almost the only source of information about the family past. This moment was vividly presented in almost all interviews with two-generation migrant families that we managed to collect in the Lipetsk region. It is characteristic that stories about the family past were perceived by both older and younger generations of migrants as the most important source of cohesion of their community in Russia, and in some cases were interpreted by informants as a special family ritual. Summing up the results of the study of the family memory of migrants in the Lipetsk region, it should be remembered that it is regional and requires comparison with other Russian regions included in the sample. However, based on the material of the Lipetsk region, we can draw a number of conclusions. Our research has shown that understanding the peculiarities of the transformation of the family memory of external migrants in Russia is unlikely to be successful without taking into account the specifics of commemorative practices and markers of the historical identity of the host society, as well as the peculiarities of the intergenerational dynamics of family commemorations in migrant communities. The use of transnationalism as a conceptual framework allowed us to consider migrants' family memorials as a configuration of narratives and practices that simultaneously take into account the historical cultures of both the country of origin and the host society. At the same time, the study showed that this configuration can change significantly due to intergenerational dynamics. A distinctive feature of Russia is the dominance of labor migration, which leaves an imprint on the peculiarities of the commemorative practices of migrants, where the role of the first generation is still key. The study revealed the preservation of the factor of family and community relations as the main reason for choosing a place of resettlement. The results of the survey and interviewing allow us to conclude that the first, one and a half and second generations of migrants are open to the Russian language and secular holidays in Russia. At the same time, migrants continue to consider the religious holidays of the country of origin and belonging to the diaspora as markers of their identity, and also continue to actively contrast the images of the host society and the country of origin, which still indicates the coexistence of communities of memory of local residents and migrants as "parallel" to each other. Among representatives of all generations, a high level of positive attitude towards the traditions of the country of origin was recorded, where it was family commemorations of traditions that turned out to be one of the most important factors in the cohesion of migrant communities. The results of a comparative analysis of the features of family memory translation in an intergenerational perspective revealed a number of differences indicating the heterogeneity of perception of images of the family past among representatives of the first, one and a half and second generations. Unlike the representatives of the first generation, their younger contemporaries indicated that their lifestyle had changed significantly after moving to Russia.

The difference between the generations is also becoming more and more apparent within the framework of involvement in the religious traditions of the country of origin. If the first generation demonstrates full involvement in religious traditions and practices, then for the one–and-a-half and especially the second generation, religious traditions are more a matter of interest rather than everyday practice. Moreover, among the representatives of the second generation of migrants in Russia, there was a noticeable tendency of a differentiated attitude towards the secular and religious traditions of the country of origin, depending on the personal ideas of the informant. Noticeable differences between generations were also revealed in the subject of nostalgia for the country of exodus. In the case of the first generation, we were faced with nostalgia for the way of life in general, especially when it came to everyday life in the USSR. In interviews with representatives of the one and a half generation, it was mostly about nostalgia for certain practices of everyday life in the country of exodus, while representatives of the second generation were nostalgic not so much for practices as for older relatives. Photography continues to play an important role for the practices of broadcasting family historical experience, as well as family rituals associated with viewing it. In general, despite intergenerational differences, the influence of the Russian education system on younger generations, as well as the digitalization of public memorials, family memory continues to be an important factor in preserving the identity of migrants in Russian society, regardless of the depth of family historical narratives, as well as the abundance of family heirlooms. Depending on the direction of the current Russian integration policy [30] and trends in the development of Russian historical culture, the further use of images of migrants' family memory may have both a conflict-causing potential and act as a platform for dialogue with other local memory communities.

References

1. Malakhov, V.S. (2014). Migrant Integration: European Experience and Russia's Perspectives: Workbook. Moscow: Spetskniga.

2. Creet, J., Kitzmann, A. (Eds.) (2011). Memory and Migration: multidisciplinary approaches to memory studies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

3. Glynn, J., Kleist, O. (Eds.) (2012). History, Memory and Migration: Perceptions of the Past and the Politics of Incorporation. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

4. Hintermann, C., Johansson, C. (Eds.) (2010). Migration and Memory. Representtions of Migration in Europe since 1960. Innsbruck: Studien Verlag.

5. Palmberger, M. & Tošić, J. (Eds.) (2012). Memories on the Move. Experiencing Mobility, Rethinking the Past. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

6. Raasch, J. (2012). Using History to Relate: How teenagers in Germany Use History to Orient between Nationalities. In History, Memory and Migration: Perceptions of the Past and the Politics of Incorporation / by I. Glynn, J. Olaf Kleist (Eds.) (pp.68-87). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

7. Üllen, S. (2012). Ambivalent Sites of Memories: The Meaning of Family Homes for Transnational Families. In Memories on the Move Experiencing Mobility, Rethinking the Past / Monika Palmberger and Jelena Tošić (Eds.) (pp. 75-99) London: Palgrave MacMillan.

8. Palmberger, M. (2016). How generations remember: Conflicting Histories and shared memories in Post-War Bosnia and Herzegovina. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

9. Mukomel', V.I. (2011). Integration of migrants: challenge, politics, social practices. Mir Rossii, 1, 34-50.

10. Dmitriev, A.V., Pyadukhov, G.A. (2011). Migrants and Society: Integration and Disintegration Potential of Interaction Practices. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya, 12 (332), 50-59.

11. Malakhov, V.S., Mkrtchyan, N.V., Vendina, O.I. (Eds.) (2015). International migration and sustainable development of Russia. Mosow: «RANKhiGS».

12. Voronova, M.V., Voronov, V.V. (2019). Analytical model of factors of adaptation and integration of migrants in the regions of Russia. Vlast, 6,69-76.

13. Bozhkov, O.B., Ignatova, S.N. (2020). Migration processes and social memory of generations. Labyrinth. Teorii i praktiki kul'tury, 1, 6-16.

14. Ovchinnikov, A.V. (2018). Cultural memory of Tatarstan migrants (based on the materials of the Armenian and Azerbaijani diasporas). In Russia: trends and development prospects. Yearbook (pp. 679-682). Moscow: Institut nauchnoj informacii po obshchestvennym naukam Rossijskoj akademii nauk.

15. Linchenko, A.A. (2020). Cultural memory of migrants and the host society in Russia and abroad: a conflict dimension. Filosofiya i kul'tura, 6, 60-82.

16. Schütze, F. (1984). Kognitive Figuren des autobiographischen Stegreiferzählens. In Biographie und Soziale Wirklichkeit: neue Beiträge und Forschungsperspektiven / Kohli, Martin (Ed.); Robert, Günther (Ed.) (s.78-117). Stuttgart: Metzler.

17. Rozhdestvenskaya, E.Y. (2012). Biographical method in sociology. Moscow: Izdatel'skij dom VSE.

18. Brednikova, O., Abashin, S. (Eds.) (2021). "Living in two worlds": rethinking transnationalism and translocality. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

19. Pries, L. (Ed.) (1999). Migration and translational social spaces. Brookfield USA: Ashgate.

20. Vertovec, S. (2004). Migrant transnationalism and modes of transformation. International Migration Review, 38, 3, 962-973.

21. Levitt, P., Jaworsky, B.N. (2007). Transnational migration studies: past developments and future trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 129-156.

22. Kapustina, E., Borisova, E. (2021). Review of the theoretical discussion about the concept of transnationalism. In "Living in two worlds": rethinking transnationalism and translocality / O. Brednikova & S. Abashin (Eds.) (pp.14-29). M.: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

23. Bryceson, D.F., Vuorela, U. (Eds.) (2002). The Transnational Family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks. Oxford: Berg.

24. Logunova, L.Y. (2011). Socio-philosophical analysis of family memory as a program of social inheritance. Dissertation. Kemerovo.

25. Volkov, V.V., Harhordin, O.V. (2008). Teoriya praktik. Sankt-Peterburg: Izdatel'stvo Evropejskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge.

26. Linchenko, A.A. (Ed.) (2020). Everyday mythology of family memory in the cultural landscape of the modern Russian province: scientific analytics and regional sociocultural practices. Lipeck: Izdatelstvo Lipeckogo gosudarstvennogo tekhnicheskogo universiteta.

27. Hirsh, M. (2021). The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. Moscow: Novoe izdatel'stvo.

28. Erll, A. (2011). Locating Family in Cultural Memory Studies. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42, 3, 303-318.

29. Woolf, D. (2003). The Social Circulation of the Past: English Historical Culture 1500-1730. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

30. Skiperskikh, A.V. (2016). Lipetsk political elite: peculiar features, personalities, incorporating trends. PolitBook, 4, 31-46.

31. Linchenko, A.A., Blaginin, V.S., Batishchev, R.Y. (2018). Cultural memory of the population of the Russian province in the situation of migration challenges (on the example of the city of Lipetsk). Gumanitarnye issledovaniya Central'noj Rossii, 2 (7), 94-105.

32. Blaginin, V.S., Linchenko, A.A., Golovashina, O.V. (2020). Festive Commemorations and Symbolic Dates in Modern Russian Migration Society. Vlast, 28, 4, 42-50.

33. Nurkova, V.V. (2006). Mirror with Memory: Phenomenon of Photography: Cultural and Historical Analysis. Moscow: RGGU.

34. Garde-Hansen, J. (2011). Media and Memory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

First Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

In the peer-reviewed article "The transformation of migrant family memory in the light of intergenerational dynamics: on the example of the Lipetsk region", the subject of the study is the influence of intergenerational dynamics on the transformation of migrant family memory in modern Russia. Accordingly, the purpose of this article is to analyze the intergenerational continuity of knowledge, values and practices of family memory of external migrants in a single Russian region – the Lipetsk region. The research methodology is based on a transnational approach, the methodological significance of which lies in the emphasis on the creation of social fields by migrant communities that cross geographical, cultural and political boundaries. At the same time, the emphasis is on the study of the practical component of the transmission of family traditions and values, rather than studying the simple level of awareness about the history of the country of origin and information about the family past. The basis for assessing the practical component of the transmission of family traditions and values was a sociological study in the form of a survey and interviews of six two-generational families. But the authors do not explicitly describe the design of the sociological survey: neither the sample, nor the time, nor the location. And this does not allow us to judge its representativeness. The relevance of the study is determined by the fact that at present the cultural integration of migrants continues to be an urgent task for most countries of the world. For the Russian Federation, the problem of migration is all the more urgent because, representing the most economically developed, socially and politically stable state, it needs additional labor resources against the background of the ongoing demographic crisis and lack of population, which leads to the need to implement a migration policy focused on attracting, adapting and integrating migrants. The scientific novelty of the publication is determined by the results of both practical and theoretical plan. The paper elaborates such a key concept as family memory, which is interpreted as a program of perception, reproduction, preservation and transmission of social heritage that has developed in the migrant's mind. Based on sociological data, a high level of openness of migrants towards certain aspects of the cultural memory of the host society in Russia, a high level of use of the Russian language in family life, acceptance and celebration of secular holidays in Russia in the family are stated. The paper attempts to reveal the mechanism of family memory translation in an intergenerational perspective, for example, through the relationship to family heirlooms. But, in our opinion, the conclusion that understanding the peculiarities of the transformation of the family memory of external migrants in Russia is unlikely to be successful without taking into account the specifics of commemorative practices and markers of the historical identity of the host society has not been confirmed in the work. This study as a whole has a certain general consistency, but leaves open the need for such a structural element of the article as "The specifics of the host society: the case of the Lipetsk region", especially in terms of presenting a sociological study of the level of openness and anxiety of residents of the Lipetsk region in relation to images of the past and memory practices of other cultures and their bearers. This element in this form does not fit into the general logic of the study, at least it does not end with any conclusions significant for the problems of the study. The article is distinguished by a certain validity of the conclusions. However, the work contains a certain number of grammatical errors (descriptions): Rossi (instead of Russia), as well as unencrypted abbreviations (NLMK). The bibliography of the work includes 34 publications. It fully corresponds to the stated topic. An appeal to the main opponents is sufficient. Conclusion: The article has scientific and practical significance. The work can be published after it is 1) either reinforced with evidence regarding the consideration of the specifics of commemorative practices and markers of the historical identity of the host society, or the article will be "spared" from this fragment; 2) a description of the design of the sociological study will be given so that its representativeness can be assessed. The results can be used in the process of implementing migration policy.

Second Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

The subject of the peer-reviewed study is the processes of transformation of family memory as one of the key factors in preserving and translating the identity of migrants in Russian society. Considering the fact of intensification of migration processes in developed societies noted by many researchers in recent decades, the relevance of studying the institutions of identity translation can hardly be overestimated. The rapid growth in the number of scientific publications devoted to the problems of collective memory and its transformation in modern society also speaks in favor of the high importance of this topic. Therefore, the author's interest in this topic is quite understandable. Moreover, the reviewed work represents the next step in a series of studies of collective memory and migration communities conducted by the research team in previous years. In theoretical and methodological terms, in addition to general scientific analytical methods, a transnational approach was used in the work, which allows us to explore the social fields created by migrants, which combine the socio-cultural practices of the host society and the country of origin. Methodically, in the process of collecting empirical material, a six-step biographical interview by Fritz Schutze was used, as well as a questionnaire based on a quota multistage sample (N=300). The collected material was statistically processed through frequency and correlation analysis. The correct application of the described methodology allowed the author to obtain results with signs of scientific novelty. First of all, the identified and analyzed specifics of the translation of migrants' family memory in an intergenerational perspective is of scientific interest: a high level of preservation of traditions and customs in the lives of the studied families, a reproducible interest in the narratives of older generations, as well as emotionally saturated memories of life in the country of exodus. These and other factors make the family a key institution for the transmission of collective memory and, consequently, the reproduction of identity. Against this background, the author's conclusion about the transformation of this institution in an intergenerational perspective is all the more interesting on the basis of recorded differences in the perception of images of the family past among representatives of the first, one and a half and second generations of migrants. It is also interesting that the fact revealed in the course of the study that one of the main reasons for choosing a place of resettlement for migrants was family and community relations. It is intuitively clear that having family and/or fraternal ties in the host country can facilitate the process of relocation and adaptation, but when this is scientifically confirmed, the status of the initial intuition changes to confirmed scientific knowledge. Structurally, the reviewed work also makes a positive impression: its logic is consistent, and the structural elements reflect the main aspects of the research. The following sections are highlighted in the text: - an uncluttered introductory part, in which a scientific problem is formulated, its relevance is justified, a brief overview of the main approaches to its solution is conducted, the theoretical context and methodological choice are carefully described and argued, the purpose and objectives of the study are set; - "Praxiological understanding of family memory", where the main approaches are critically analyzed The "post-metaphysical", activity-based understanding of the institution under study is argued for; - "Culture of the host society in the family memory of migrants", which presents an analysis of the perception of cultural practices of the host society through the prism of family memory; - "Features of the translation of family memory of migrants in an intergenerational perspective", which analyzes the refraction of the problems of family memory in an intergenerational perspective; - the uncompleted final part, which summarizes the results of the study, draws conclusions and outlines some prospects for further research. Stylistically, the article also gives a very good impression of a well-designed study: it is written quite competently, in a good language, with the correct use of special scientific terminology. The bibliography includes 34 titles, including studies in several foreign languages, and well reflects the state of scientific research on the subject of the article. The appeal to the opponents takes place in terms of discussing the methodological choice, as well as the main approaches to understanding the institution of family memory. The GENERAL CONCLUSION is that the article proposed for review can be qualified as a qualitatively completed scientific work that meets all the requirements for works of this kind. The level of the analysis carried out, the skills of using methodological tools, as well as the design of the results obtained indicate that the author has research experience. The presented material corresponds to the subject of the journal "Sociodynamics", and the results obtained will be of interest to political scientists, sociologists, cultural scientists, conflict scientists, specialists in the field of public administration, migration research, as well as for students of the listed specialties. According to the results of the review, the article is recommended for publication.

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|