|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

PHILHARMONICA. International Music Journal

Reference:

Balbekova I.M.

Creative rotation in conceptual art: Marcel Duchamp – composer, John Cage – artist

// PHILHARMONICA. International Music Journal.

2022. ¹ 2.

P. 22-36.

DOI: 10.7256/2453-613X.2022.2.37645 URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=37645

Creative rotation in conceptual art: Marcel Duchamp – composer, John Cage – artist

Balbekova Irina Mikhailovna

Postgraduate student, Department of General Humanities and Social Sciences /Department of Theory and History of Art, Autonomous Non-profit Organization of Higher Education "Institute of Contemporary Art"

121309, Russia, Tsentral'nyi Federal'nyi Okrug avtonomnyi okrug, g. Moscow, ul. Novozavodskaya, 27a

|

balbekova77@mail.ru

|

|

|

Other publications by this author

|

|

|

DOI: 10.7256/2453-613X.2022.2.37645

Received:

06-03-2022

Published:

23-04-2022

Abstract:

The subject of this study is the intersection points of music and fine art, demonstrated by the example of the creative interaction of the conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp and composer John Cage. The possibility of reformatting creativity from the visual to the sound field is considered as a role rotation, within which Duchamp appears as a composer, and Cage as an artist. An attempt is made to explain the motivation for such a choice. What is the meaning of this, and what do people mean when they choose this or that image for themselves, and create this or that image for themselves. How important it is to change the artistic image and creative image for the master. The methodology of the research consists in a comparative analysis of these concepts using already known works on this topic and personal observations of the author. In conceptualism, an idea is valued above the process of its materialization in a work of art, and therefore, the technique of execution is not a decisive factor. In such a creative paradigm, the artist's tools themselves become not so essential, which can be paints, a brush or other means of visual representation of the concept, as well as sheet music or a graphic score. The means of artistic expression - sounds or visual elements – also turn out to be equivalent. All of them focus around the concept - the dominant point of any kind of creativity. This conclusion becomes the key for the conducted research in this article.

Keywords:

artistic image, Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, artist, composer, music, painting, creative thinking, divergent character, notation

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

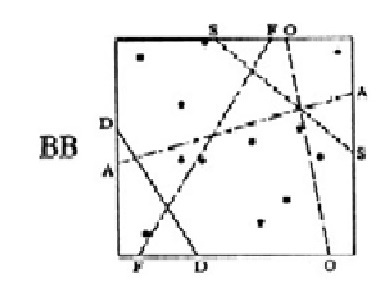

In recent years, both in foreign and domestic art criticism, there has been a growing interest in the mutual influence and synthesis of music and fine art of the XX century. The art of conceptualism is becoming an equally important research perspective. This is due to the fact that neo-conceptualism, the modern stage of the development of conceptualism of the 1960s and 1970s, is receiving a vivid development in modern culture. As well as conceptual art, its form is primarily the art of issues concerning its self-determination of art, as well as appealing to politics, media and society. In connection with these circumstances, the research topic of this article turns out to be very relevant. In this work, the starting point is the conceptualist form of synthesis in the art of the twentieth century, which allows moving the artistic focus from one area to another. From this position, the point of view of the creator of the concept of "Languages of Art", Nelson Goodman, is important [1], as well as the works of Erhardt Karkoshka [2] and the study of musicologist Elena Dubinets "Signs of Sounds" [3] become important sources. The methodology is based on a comparative analysis of theories and concepts of already known works on this topic and personal observations of the author. The modern notation used in the music of the XX – XXI century is a focus of various symbols, both denoting specific sound structures and phenomena, and in some cases being a representation of a graphic form of artistic expression in which the designations are not specific. They are rather metaphorical and look like visual equivalents of certain sound entities, the exact encoding of which does not exist. The purity of the reproduction of such a text is not subject to discussion, and the performer must rely on his intuition and creative potential. E. Dubinets writes at the beginning of his research: "The notation of a significant part of modern music looks very complicated and rather confusing. The unusual nature of the musical text, the variety of verbal instructions, non-traditional signs and symbols often do not allow you to quickly orient yourself in the score. A musician needs a lot of time, certain knowledge and skills to understand the intentions of the composer" [3, p.5]. In the XX century, a total variety of forms of fixation of sound elements appears in new music, decentralized and aimed at different aspects of musical composition. In this connection, the question arises as to what exactly the composer means in relation to each individual visual element, in the absence of unification, and how they should work to create a complete composition. Today, the process of concretizing the idea and explaining the forms of fixation of the material is expressed in the composer's "Legend", which is presupposed by the publication of musical material. To understand the principles of notation, it is necessary to understand the composer's individual creative method, the specifics of his style, his writing techniques, and the aesthetics of his work [3, p.11]. The problem of the correlation of notation and composition methods is one of the key problems in modern composing and performing art. Composers decide in their own way how to write down their musical thoughts most clearly – so that the performer can adequately express them in sounds. In turn, a musician who has modern works in his repertoire should be able to correctly read the author's notation signs [3, p.8]. The latter task is gradually becoming more complicated: almost every composer strives to contribute to the history of notation by composing more and more new symbols. Modern authors introduce their innovations in different ways: some describe in detail all the musical notation signs in the prefaces and comments to the scores, others give musicians the right to freely interpret the notation. A performer learning modern music often has to first master the new principles of musical notation of their implementation [3, p.8]. The conclusion from these processes, which Dubinets writes about, is that new music needs a new notation, freed from the binding framework of any tradition. And the change in the concept of music is associated with a change in the picture of the surrounding world [3, p. 10]. Standard musical notation can be reinterpreted in such a way that its signs differ significantly from the generally accepted ones, or even do not contain accurate musical representations at all. In addition, in some cases, the notation system can classify images according to the size and shape that are at the center of the composer's idea (Fig. 1).

Fig.1. Musical notation consists not only of specific musical symbols in the form of notes, but also of alphabetic, numeric designations and symbols, as well as words and expressions taken from verbal language. For example, the designation of the tempo of the performance of the work: allegro, moderato, adagio; or the designation of the nature of the music: dolche, agitatto, cantabile. Such designations are not an integral part of the score, but rather become auxiliary instructions, the observance or non-observance of which affects the quality of performance, but not the identity of the work.

The overwhelming monopoly that standard musical notation had for a long time inevitably inspired opposition to it and the possibility of alternative proposals. The composers were not satisfied that the scores created in the traditional form of notation provided them with too narrow a set of functions, prescribed the rules too precisely, or vice versa, not accurately enough. The transformation process in this case is aimed at greater, lesser, or some other control over the means of expression and graphic representation of musical material [1, 187]. In the 1950s, as part of the activities of the composers of the so-called New York school, composers John Cage, Morton Feldman, Earl Brown and Christian Wolf began to develop new forms of recording. The central category of this form of recording is uncertainty or indeterminacy, through which the composer provides the performer with freedom and the possibility of framework improvisation. John Cage is one of the most outstanding artists of the XX century. The self-proclaimed polymath Cage was engaged in a wide range of activities, including music, fine arts, literature, teaching and even mycology (the study of mushrooms)! He claimed that he became interested in mycology by chance because it was next to music in the dictionary. The lesser-known, artistic aspect of Cage's work expands our understanding of his work, his personality and, most importantly, his legacy as one of the most outstanding people. One simple system developed by John Cage is something like this (Fig. 2)

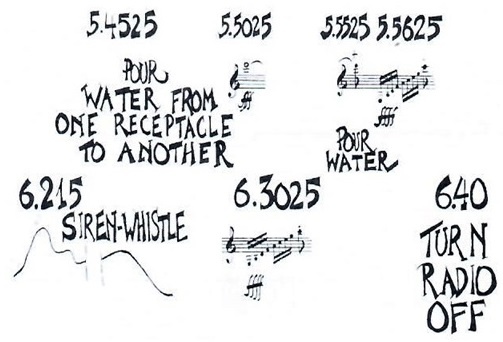

Fig. 2. The points for individual sounds are placed in a rectangle; across the rectangle, at different angles and possibly intersecting, five straight lines pass to determine separately the frequency, duration, timbre, amplitude and sequence. Significant factors determining the sounds denoted by a dot are the perpendicular distances from the dot to the string [1, p. 188]. In "The Music of Water" (1952), sound events occur independently of each other at certain points in time: the performer pours water from one container into another (fragment 5.4525), turns on and off the radio (fragment 6.40), blows whistles (fragment 6.215), violating traditional ideas about art. Such recording systems are not notation in the usual sense and provide the performer with no means for accurate reproduction from performance to performance. There are only copies of a unique object, interpreted by each performer in their own way. Some composers use recording systems that only marginally restrict the freedom of the performer. On the other hand, composers working in the field of electronic music, with new sounds and acoustic means, strive in some cases to eliminate any freedom in performance and achieve precise control, and in others they offer a graphic version of notation. Many symbol systems developed by modern composers have been described, illustrated and classified by Erhardt Karkoshka [2]. Its classification offers the following four main types of systems: - precise notation, where each note is defined by all its parameters and named; - range designation when only the limits of the range in height, dynamics, duration and other parameters are specified; - suggestive notation (Hinweizende notation), which defines the relationship between notes, approximate ranges and verbal descriptions; - musical graphics, represented by diagrams, graphs, sketches. Non-motivational and non-linguistic system [1, p.191]. Let's take a closer look at the music graphics, as the most reflective of the subject of the article. Music and fine art have always been closely interrelated. Back in the XIX century, it was considered good form to comprehensively develop a person in various fields of art. Musicologist V. Giseler notes that once the image and sound had a common homeland and now they must find it again. He also suggests that graphic composers seek to discover the inaudible in music [4, pp. 27-33]. Graphic notation originated and became quite widespread in the late 40s – early 50s of the twentieth century. Although the first unsystematic experiments of this kind have occurred before. Musicians and composers became cramped within the framework of traditional notation, which had developed in the XVII century. The existing arsenal of expressive graphic symbols was no longer able to reflect the composer's intention, on the one hand. On the other hand, the musicians sought to solve another task – to bring the author and the reporter closer, that is, the one who somehow perceives the score: the performer, the viewer, the listener. In other words, both the musician and even the listener, the viewer are co-authors of a musical work [3, p. 38].

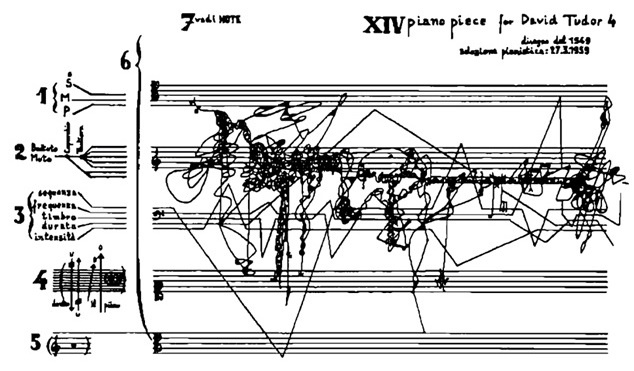

Nelson Goodman in the book "Languages of Art" shows the fundamental differences between traditional notation and graphic notation. "Since the artist's sketch and the composer's score can be used as a working guide, the fundamental difference in their status may go unnoticed. The sketch, unlike the score, is not written at all in a language or notation, but in a system without syntactic or semantic differentiation." "The sheet music language of musical scores has no analogues in the language of sketches" [1, pp. 192-193]. There is no such system of symbols and symbols for painting as there is for music. The score can be performed by different musicians with varying degrees of approximation in the same way, thanks to the generally accepted system of music notation. Is it possible to create a copy of the painting based on some verbal, symbolic, symbolic description? Obviously not. This aspect attracted, among other things, the attention of musicians and composers to such an unusual technique as graphic notation. When a drawing, sketch, diagram can be interpreted by the performer as you like, depending on his vision, associations, feelings and imagination. Graphic notation synthesizes music and visual art, making music accessible to the average listener, and not only to musically educated people. "The role of these scores is the same as that of abstract painting: the arousal of subjective associations" [5, pp. 215-272]. Graphic scores became an autonomous, self-sufficient part of creativity, often not requiring sound implementation. That is, they acquired common features with works of painting, having a purely aesthetic value. For example, S. Bussotti. "Piano piece for David Tudor" (Fig. 3). From the point of view of writing in graphic notation, two main directions can be distinguished: discursive and suggestive [6, pp.109-113]. The first involves the use of signs of traditional notation, although in a much modified, conditional form. And in the second there is not even a hint of notation, it is rather a work of painting for visual perception, but with the possibility of musical embodiment. So, one of the prerequisites for the emergence of alternative types of notation is the very dictates of time, the emergence of new trends in art, the denial of age-old traditions, the search for new forms and expressive means, synthesis, fusion of different types of art. This can be called external, objective factors. Synesthesia is a phenomenon of perception in which the irritation of one sense organ (due to the irradiation of excitation from the nervous structures of one sensory system to another), along with sensations specific to it, causes sensations corresponding to another sense organ [7]. So, for example, some people are able to  Fig. 3. to see the color of music, to place numbers and letters in an imaginary space, to hear sounds when contemplating pictures of nature. Synesthetes use their abilities to memorize names and phone numbers, perform mathematical procedures in their minds, as well as in more complex creative activities such as visual arts, music and theater. Researchers have described different forms of synesthesia. We are primarily interested in such a form as chromesthesia (phonopsia) – the union of sounds and colors. For such people, different sounds – natural, everyday, technical, musical – evoke a sense of color, the visual range is associated with different colors. For example, many musicians and composers have each tonality has its own color; the tempo of performance, the texture of music also have their own color and graphic associations. Moreover, there is no single color-sound system, everyone feels it in their own way. It is obvious that both M. Duchamp and J. Cage possessed these qualities, which is confirmed by the facts of their creative life and research materials of various authors. Duchamp's interests were very extensive: painting, sculpture, music, chess, exhibitions, invention, new scientific ideas. It is at the junction of different areas of activity that new things are born. We can say that Duchamp with his urinal put a checkmate to the whole world of art! Contemporaries were clearly convinced that it is possible, it turns out that it is. And this applies not only to painting, but to other types of art – music, literature, dance, theater. With their experiments with music, Duchamp, and then Cage with artistic experiments, laid the foundations for rapprochement, synthesis of music and the art of painting. Cage's phrase doesn't seem strange anymore: "If you want to study music, study Duchamp." A vital topic is the idea of notation, or the relationship between visual signs or gestures and music. Throughout his creative activity, Cage constantly remade and invented scores, turning them into a unique sculptural and visual object, recreating a kind of interface between the performer and the music. The exhibition of Cage's visual works, "Every Day is a Good Day" is interesting because it presents drawings, engravings and watercolors by the artist, known primarily as a composer. Although Cage separated his artistic works related to the field of fine art from his musical compositions, they were undoubtedly interconnected and fed from each other [8]. Changing the positions of the artist – organizer of sounds, as Cage positioned the activity of the modern composer, to the creator of images, or the author of the ready-made to the position of the composer — from the point of view of chess strategy looks like a change of "white" to "black".

A few examples of the transformation of artists into musicians and vice versa - musicians into artists. Felix Mendelssohn is a German composer. Everyone knows his "Wedding March", but the fact that he was also an artist is a discovery for many. He created more than 300 works of art. Paul Klee is a German and Swiss artist, graphic artist, art theorist, one of the largest figures of the European avant–garde. He received a musical education and a talented violinist was invited to the Bern Music Community. Frank Sinatra is an American film actor, film director, producer, showman, singer, conductor. Winner of the Oscar Film Award. He became a Grammy Award winner eleven times. Frank came to visual art forms towards the end of his life. The Frank Sinatra School of Art was opened in his honor. Bob Dylan is an American author–performer, artist, writer and film actor. His works have been exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in London.[9] Let's take a closer look at the interpretation of Duchamp as a composer and Cage as an artist. Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) is one of the iconic figures in the art of the post—war avant-garde of the twentieth century. His work influenced the formation of surrealism and Dadaism, the formation of pop art, minimalism and conceptual art[10], although it never belonged to any particular direction. In this respect, Duchamp can be compared with the great composer of the twentieth century John Cage (1912-1992): in some cases, the latter is being considered minimalism, in others — conceptualism, despite the fact that Cage's ideas went beyond each of these directions. We believe that Duchamp's work was partly close to Cubism, futurism, and surrealism, but we cannot imagine him from within only one of these directions. The first two decades of the twentieth century were the period of Duchamp's greatest creative activity. Then he moved away from direct artistic activity, partly because he considered himself misunderstood by his contemporaries. Starting in the twenties, Duchamp almost completely focused on chess, performed a lot in tournaments of various levels, played for the French national team at the World Cup, wrote a book about the tactics of the chess game. But sometimes he participated in the organization of art exhibitions, both collective and his own [11]. Duchamp's interest in music was rather insignificant in comparison with the visual arts. But the phenomenon of Duchamp-composer had a noticeable impact on the musical art. His creative legacy includes only two works, but they represent a radical departure from everything that was done up to that time [12, p.176]. Duchamp anticipated in his music what then became apparent in the visual arts, especially in the Dada movement: art is here for everyone, not just for qualified professionals. Duchamp's lack of musical education could only improve his knowledge of compositions. His works are completely independent of the prevailing musical style of the beginning of the century. Duchamp's main discovery in this area is the interpretation of randomness as a compositional method and, in addition, the invention of special ready-made sounds. John Cage, paying tribute to Duchamp's musical experiments, admitted that he was inclined "to perceive him more and more as a composer" [13, p.151]. Duchamp created his first composition, "Musical Typo" ("Erratum Musical") for a vocal trio, presumably around 1913. The piece became one of the first examples in the history of music of the use of random selection to create a compositional whole. The score of the "Musical Typo" is divided into three parts, each of which has its own special name: "Yvonne", "Magdelaine" and "Marcel". The listed "names" of the segments indicate the addressees and at the same time the first performers of the play: Duchamp himself and his two younger sisters — Yvonne and Magdalena. T. de Duve, presenting Duchamp's painting "Sonata" (1911), gives the following description: "She [the painting] again paints a family, ritual scene: home music playing on the day of the Duchamp's main family holiday — New Year. The mother dominates the picture, Madame Duchamp, Yvonne plays the piano, Magdalena plays the violin..." [14, p.104]. The play was created with the help ofa few special cards that denoted a certain note. Duchamp produced three series (according to the number of performers), each of which included twenty-five cards. Each series was placed in a hat, where the cards were thoroughly mixed, and then alternately extracted, forming a certain musical sequence. As a result, by recording the notes strictly in the order of their extraction from the hat, Duchamp received a ready-made melodic line for each voice. But Duchamp's musical interests also had a second side, unrelated to composing – the creation of sound "ready-made", close in their properties to musical instruments. One of the striking examples of such constructions is ready-made "With Hidden Noise" ("With hidden noise", 1916). It is a small ball with strings stretched between two copper plates, which were driven with the help ofby rotating four oblong screws. In the early 1960s, Duchamp's experiments were continued by a number of authors, including Nam June Pike ("Urmusic", 1961) and Robert Morris ("Thebox with the Sound of Its Own Making", 1961). The "Duchamp effect" can also be seen in the gradual transformation of musical instruments into original "objects". This process, picked up by Duchamp's contemporaries and followers, led to a significant expansion of sound capabilities and, as a result, to going beyond the purely musical sphere (Armand, "Chopin'swaterloo", 1963).

Duchamp's experiments, which introduced randomness as an independent compositional method and anticipated the appearance of aleatorics, played a huge role in the development of musical art. Two of his small scores and the "sounding" ready-made ones still retain their relevance, manifest themselves in one form or another and thereby confirm the value of Duchamp's discoveries for modern cultural reality [15, pp. 38-41]. John Cage once said, "One way to study music is to study Duchamp."[16] Both of these unusual creative personalities contradicted the stereotypes of perception of both artistic creativity and the expectations of the viewer. So for Cage, silence was an instrument of composition, proof that it could also be music. Duchamp, on the other hand, was interested in whether it was possible to visualize sound by playing music in a random order, and at the same time create something artistic by chance. John Cage was closely associated with art and artists throughout his long creative career, although it was only in the mid-sixties that he began to seriously engage in fine art. In 1969, he completed the first major visual project in response to the death of Marcel Duchamp. The project was a series of sculptures made of plexiglass [17]. And in 1978 invited Kathan Brown Crown Point Press to compete in a series of prints. Although Cage resisted at first, he accepted the invitation and began making a series of etchings. He continued this, along with drawings and watercolors, throughout his life. It is this volume of work that is primarily presented in "Every Day is a Good Day". Over the last 15 years of his life, Cage has produced more than 600 prints with the PointPress crown in San Francisco, as well as 260 drawings and watercolors. In these works, he used the same randomly determined procedures in his works as in his musical works. In the UK, there was the first major retrospective of Cage's visual art. The exhibition featured more than 100 drawings, engravings and watercolors, including the extraordinary Ryoanji series, described by art critic David Sylvester as "one of the most beautiful engravings and drawings made anywhere in the 1980s" [17]. In these works, he outlined the contours of stones scattered (by chance) on paper or printed form, in one case he outlined 3,375 individually arranged stones. He also experimented with firing or soaking paper and applied complex, painstaking procedures at every stage of the printing process. Inspired by Cage's use of random procedures, the exhibition was markedly different from a traditional touring exhibition. The compositional process, which Cage often used, using a computer program for generating random numbers, similar to the Chinese oracle "I Ching", was carried out to determine the number of exhibited works, their position on the wall and the number of changes that can occur in each place. Cage said that he used random operations instead of acting according to his likes and dislikes. He wanted to be open to new possibilities beyond what he could naturally think of. After receiving a copy of the I Ching in 1951, he then invented a computer program of random numbers as a means to detach himself from the process at certain points. He set well-defined parameters, carefully formulating questions that the randomness of the operation then "answered". A similar computer program was used when hanging paintings at the exhibition. The program dictates how many works should be posted, where they are placed on the walls and how many times the exposition changes. The exhibition featured 135 works on paper, including engravings, drawings and watercolors. In the spirit of Cage, 30 of these works were removed and replaced with "empty spaces" at the exhibition. There are several series featured in the exhibition, although due to the way the exhibition was hung, the series do not appear in any particular order. "Changes and Disappearances" is a series of very works that took years to complete. Cage experimented with burning or soaking paper and applied indeterminism at every stage of the printing process. Each line and edge of the plate were painted in different, individually mixed colors. As the series progressed, the composition of the works grew – the last print in the series contains 298 colors. Inspired by his fellow artist Ray Kass, Cage decided to try his casual operations in other media and produced a series of watercolors "The New River Series" in his studio in New York. He experimented by painting with wide brushes and feathers, and especially admired the transparency of the erased fragments. Here he used his usual random operations to determine both the composition and the choice of materials. The philosophy of Zen Buddhism teaches us that if some activity becomes boring after 2 minutes, you should try it 4 more. If it's still boring, try to do it in 8, then in 16, 32. In the end, you will certainly find that this activity is not boring at all, but very interesting. It was a philosophy that Cage used when creating his works directly related to many of his hobbies. Undoubtedly, a vital topic is the idea of notation, or the relationship between visual signs or gestures and music. Throughout his creative activity, Cage constantly remade and invented scores, turning them into a unique sculptural and visual object, recreating a kind of interface between the performer and the music. The exhibition of Cage's visual works, "Every Day is a Good Day" is interesting because it presents drawings, engravings and watercolors by the artist, known primarily as a composer. Although Cage separated his artistic works related to the field of fine arts from their musical compositions, they were undoubtedly interconnected and fed from each other [17]. In psychology, creative activity is defined as the desire to create something new: paintings, music, scientific theories, buildings, mechanisms, culinary recipes, teaching methods, methods of activity, etc. There is a reproductive activity - replication, performing operations on a pattern learned by a person in the learning process. And if a person invents something of his own, does it in a new way, then this is creativity.

The result of this increased interest was the development of the psychology of creativity and the development of the theory of creative thinking. Thanks to the research of such scientists as J. Guilford, E. de Bono, G. Altshuller, S. Mednik, T. Buzen, Ya. Ponomarev and others, the main characteristics of this unusual type of thinking have been identified. - Divergent character. From the point of view of J. Guilford, divergence (orientation in different directions) – the main sign of creative thinking. This distinguishes it from convergent, unidirectional logical thinking.

- Imagery. Creative thought is born in the form of an image, which was noticed by A. Einstein. Creative ideas are put into words only in the process of developing and communicating them to other people. Therefore, creativity is most clearly manifested in the field of art, which operates with images.

- Associativity. Associations are connections that arise in the brain between different elements or blocks of information. They help to connect the most diverse areas of our experience, knowledge, and ideas to thinking. The more such associations arise, the more interesting and original thoughts are born.

- Spontaneous activity of the imagination. A creative person not only thinks in images, they are born spontaneously in his brain, without much effort, thanks to a developed imagination.

In addition to special thinking, imaginative memory plays an important role in the cognitive sphere of a creative personality, helping to preserve a lot of useful information, and the ability to focus on their activities. Well-managed, developed attention combined with imagination allows creative people to notice unusual, amazing things in the world that others do not see [18]. A creative person is an individual who has a stable and irresistible need for creativity and sees in it the main meaning of his life [19]. For both Duchamp and Cage, the whole meaning of life was a constant creative search and understanding of the phenomena of art and life in all its aspects. The horizons of everyone's interests stretched far beyond any one kind of art. In different periods of life, one thing could prevail over another, for example, chess over painting, sculpture over music, music over drawing. The possibility of reformatting creativity from the visual to the sound field can be represented as a role rotation, in which Duchamp is a composer and Cage is an artist. In addition to psychological factors, this explains the main thing in their work: simultaneously uniting these two figures and allowing them to form cross-links in creativity. Both Cage and Duchamp belong to conceptual art. In conceptualism, it is difficult to be a professional or an amateur, since the technique of performing a conceptual work of art is a technique of creating an original bright unusual idea that shifts the focus from the subject to the concept underlying its creation. The more original the idea, the longer the work of conceptual art lives. In conceptualism, it (that is, the idea) is valued above the process of its materialization in a work of art, and therefore, the technique of execution is not a decisive factor. In such a creative paradigm, the artist's tools themselves become not so essential, which can be paints, a brush or other means of visual representation of the concept, as well as sheet music or a graphic score. The means of artistic expression - sounds or visual elements – also turn out to be equivalent. All of them focus around the concept - the dominant point of any kind of creativity.

References

1. Goodman, Nelson. Languages of Art//1976. Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN-0915144352. p.291.

2. Karkoshka, Erhard. Notation in New Music; a critical guide to interpretation and implementation. // 1972. New York, Praeger, 183 pages.

3. Dubinets E.A. Signs of sounds: About a lie.music. notations// Moscow State Conservatory named after P.I. Tchaikovsky. 1999. Gamayun, Kiev. 314 pp .(accessed: 12.09.2021)

4. Giezeler Z. Zur Semiotic graphischer Notation// Melos, 1978. – ¹1. – P.27-33.

5. (Matveev V., Matveeva S. Evolution of the musical avant-garde and its attitude to the public. // Modern bourgeois art. Criticism and reflections.-M. 1975.,-pp. 215-272.)

6. Ukhov D. Notation in modern jazz// Ars Notandi. Notation in a changing world.-M., 1997.-pp. 109-113.

7. Synesthesia. [Electronic resource]: Wikipedia. Update date: 11/21/2019. URL:https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/ñèíåñòåçèÿ . (accessed December 2021).

8. Cage J., Wright L., Millar J. Every Day is a Good Day: The Visual Art of John Cage. Hayward Publishing. 2010. P.160. ISBN: 978-1853322839

9. Musicians-artists: love of art in different forms [Electronic resource] 15.07.2018. URL: https://musicseasons.org/muzykanty-xudozhniki-lyubov-k-iskusstvu-v-raznyx-formax / (accessed: 07.10.2021)

10. Shannon Â. Designing chess men ataste of the imagery of chess [Ýëåêòðîííûéðåñóðñ]. URL: http: // www.worldchesshof.org. (äàòà îáðàùåíèÿ: 17.08.2020).

11. Shishkina G.A., Marcel Duchamp-musician: between chance and regularity // Musical education and science. 2017. No. 1(6). pp. 38-41. ISSN: 2413-0001.

12. Lexicon of nonclassics. Artistic and aesthetic culture of the XX century / edited by V. V. Bychkov. M.: ROSSPEN, 2003. 607 p., p.176.

13. Stevance S., Flint de Medicis C. Marcel Duchamp’s Musical Secret Boxed in the Tradition of the Real: A New Instrumen¬tal Paradigm // Perspectives of New Music. Vol. 45. ¹ 2. P. 150–170.,Ð.151.

14. Duv T. Pictorial nominalism: Marcel Duchamp, painting and modernity / trans. from fr. Shestakova. M.: Publishing House of Gaidar Institute, 2012. 368 p., p.104.

15. Shishkina G.A., Marcel Duchamp-musician: between case and regularity // Musical education and Science. 2017. No. 1(6). pp. 38-41. ISSN: 2413-0001.

16. Cross L. Reunion: John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Electronic Music and Chess // Leonardo Music Journal. 1999. No. 9

17. Cage J., Wright L., Millar J. Every Day is a Good Day: The Visual Art of John Cage. Hayward Publishing. 2010. P.160. ISBN: 978-1853322839.

18. Golubeva M.V., Creative personality – who is it in psychology. Features, signs, psychological portrait [Electronic resource] URL:https://psychologist.tips/4216-tvorcheskaya-lichnost-kto-eto-v-psihologii-osobennosti-priznaki-psihologicheskij-portret.html (date of address: 23.09.2021)

19. Guzenkov S., Creative personality is: unexpected signs [Electronic resource] 28.10.2019. URL: https://www.nur.kz/family/self-realization/1824465-tvorceskaa-licnost---eto-neozidannye-priznaki / (accessed: 08/03/2021)

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

To the journal "PHILHARMONICA. International Music Journal" the author presented his article "Creative rotation in conceptual art: Marcel Duchamp is a composer, John Cage is an artist.", in which a study of the mutual influence and synthesis of music and fine art of the twentieth century is conducted on the example of individual representatives. The author proceeds in the study of this issue from the fact that the directions of conceptualism and neo-conceptualism, which are a manifesto of synthesis in art and the movement of artistic focus from one sphere to another, appear to be the focus of a scientific research perspective. The issues of self-determination and self-expression of art, its presentation and impact on society are at the center of research interest. This position is the relevance of the study. The scientific novelty of the research lies in the comparative analysis of the creative activity of M. Duchamp and J. Cage as characteristic representatives of these trends. The theoretical basis of the study was the theories of N. Goodman, E. Karkoshka, E. Dubinets and others. The empirical material was the works of Duchamp and Cage. The methodological basis of the study was the method of comparative analysis. The purpose of the research is to analyze the conceptualist form of synthesis in the art of the twentieth century, which allows moving the artistic focus from one area to another. To achieve this goal, the author sets the following tasks in the study: to study and analyze the methods of notation used in the compositional and performing arts of the XX – XXI century, as well as to conduct a comparative analysis of the activities and innovative experiments of the composer M. Duchamp and the artist J. Cage. Based on the concepts of E. Dubinets and N. Goodman on the symbolism of the language of arts, the author notes the changes taking place in the compositional art within the framework of conceptualism and neo-conceptualism. Based on the position of conceptualism that the idea is primary, and its expression is secondary, the author states that modern notation in music bears little resemblance to traditional musical notation. In the XX century, a total variety of forms of fixation of sound elements appeared in new music. Each composer strives to bring a personal component to notation by inventing new symbols and ways to display their own unique musical discoveries. Musical notation ceases to be traditional and systematic. All this makes the scores difficult for the musician to perceive, as a result of which even reading sheet music began to require certain skills and abilities in addition to traditional musical education. Some composers provide their works with detailed comments and transcriptions, while others do not provide explanations. In the 1950s, as part of the activities of the composers of the so-called New York school, composers John Cage, Morton Feldman, Earl Brown and Christian Wolf began to develop new forms of recording. The central category of this form of recording is uncertainty or indeterminacy, through which the composer provides the performer with freedom and the possibility of framework improvisation. Thus, the composer, the performer, and even the listener are involved in the process of creating a musical work. A similar situation is observed in conceptualist visual art. Considering various variants of notations and relying on the classification of E. Karkoshka, the author identifies four main types of systems: precise notation (each note is defined by all its parameters and named); range designation, when only the limits of the range in height, dynamics, duration and other parameters are indicated; suggestive notation (Hinweisende notation), which sets the relationship between notes, approximate ranges and verbal descriptions; musical graphics, represented by diagrams, graphs, sketches (non-sensational and non-linguistic system). As part of the subject of his research, the author analyzes in detail the system of musical graphics, comparing it with abstract painting, the purpose of which is to "excite subjective associations." In graphic notation, the author identifies two main directions – discursive and suggestive. "The first involves the use of signs of traditional notation, although in a much modified, conditional form. And in the second one there is not even a hint of notation, it is rather a work of painting for visual perception, but with the possibility of musical embodiment." The author states that most creative personalities of the twentieth century are distinguished by a wide range of interests and the use of talents. For example, M. Duchamp, F. Mendelssohn, F. Sinatra proved themselves both as musicians and as artists. Special attention should be paid to the author's detailed study of the work of M. Duchamp and J. Cage. The author draws parallels and notes the features characteristic of both artists. They were synesthetes, which determined the emergence of innovative ideas in their work. The fields of application of their talents are quite extensive: chess, music, fine arts, sculpture, invention. Their work went beyond any particular direction and had a great influence on their followers. All their works of art are interconnected and interdependent. Their creative path is marked by constant searches and experiments in various fields of art, reformatting creativity from the visual to the sound field. After conducting the research, the author presents conclusions on the studied materials, noting that in conceptualism, the technique of performing a work of art is a technique for creating an original bright unusual idea that shifts the focus from the subject to the concept underlying its creation. The idea is valued above the process of its materialization. Any means of visual representation of the concept can act as a toolkit, all of them turn out to be equivalent. It seems that the author in his material touched upon relevant and interesting issues for modern socio-humanitarian knowledge, choosing a topic for analysis, consideration of which in scientific research discourse will entail certain changes in the established approaches and directions of analysis of the problem addressed in the presented article. The results obtained allow us to assert that the study of various forms and trends in art, their mutual influence and interpenetration is of undoubted theoretical and practical cultural interest and can serve as a source of further research. The material presented in the work has a clear, logically structured structure that contributes to a more complete assimilation of the material. An adequate choice of methodological base also contributes to this. The bibliographic list of the study consists of 19 sources, including foreign ones, which seems sufficient for generalization and analysis of scientific discourse on the studied problem. The author fulfilled his goal, received certain scientific results that allowed him to summarize the material. It should be noted that the article may be of interest to readers and deserves to be published in a reputable scientific publication.

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|