|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

Genesis: Historical research

Reference:

Dordzhieva E.V.

The image of the Kalmyks in the descriptions of foreign travelers of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century

// Genesis: Historical research.

2024. є 1.

P. 1-19.

DOI: 10.25136/2409-868X.2024.1.69472 EDN: CDHETF URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=69472

The image of the Kalmyks in the descriptions of foreign travelers of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century

Dordzhieva Elena Valerievna

ORCID: 0009-0007-3399-9024

Doctor of History

Professor, Department of Social and Human Sciences, MIREA - Russian Technological University

119435, Russia, Moscow, Malaya Pirogovskaya str., 1 p.5, room B-302

|

evdord@yandex.ru

|

|

|

Other publications by this author

|

|

|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-868X.2024.1.69472

EDN: CDHETF

Received:

26-12-2023

Published:

02-01-2024

Abstract:

The purpose of the work is to identify the features of the formation of an ethnic image and its constituent elements, which have become widespread in the works of foreigners. The subject of this article is the image of the Kalmyks, created by foreign travelers of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century. The research material is travelogues by foreign authors, which allow taking into account the subjective moment of perception, revealing the problem of historical reality and its representation in a historical source. The article assumes the solution of the following tasks: 1) identification of the factors that led to the perception of Kalmyks by observers, 2) description of the means used by foreign travelers, recreating in travelogues the main features of the image of Kalmyks, and their worldview, which influenced the construction of this image, 3) assessment of the socio-cultural consequences that arose as a result of the formation of ethnic stereotypes about Kalmyks. The historical discourse of otherness is revealed using the method of semiotics. The analysis of narrative details and the logic of the text revealed information about foreigners' ideas about Kalmyks and stereotypes associated with the perception of the "Other". The theoretical and methodological basis of the article is the works of Russian and foreign researchers in the field of imagology. There are no special imagological studies in Kalmyk historical science, which gives relevance to this work. The novelty of the work lies in the correlation of travelogues' information about the Kalmyks with the civilizational models prevailing in the public consciousness of observers in the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century. Through the semiotic analysis of texts, the systematization of travelers' value judgments has been carried out. The results obtained indicate that the structure of the ethnic stereotype is characterized by a certain task. Foreigners' ideas about Kalmyks allowed them to take an inside look at their imaginary universe. Travelers imagined their world to be the center of the universe, on the outskirts of which were the Kalmyks barbarians. When explaining the difference between the "own" and "alien" world, the authors used the techniques of comparison and inversion. The interpretation of Kalmyk realities is achieved with the help of such a topos of ethnographic discourse as a story about miracles. Through the denial of negative traits attributed to "Others", one's own identity is being formed, a stable image of "One's Own". The ideas of travelers influenced the formation of the image of the Kalmyks in Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

Keywords:

travelogue, image of another, Kalmyks, foreigners, travelers, stereotype, representation, national character, identity, orientalism

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

Introduction. In historiography, the representation of national character from the perspective of the "Other" in the notes of foreign travelers is considered as a component of the problems of national identity. In everyday consciousness, nations, like individuals, possess a set of stable traits. The sense of community is based on stereotypical images of "Others". The problem of overcoming stereotypes and forming a dialogue is one of the most urgent in the life of society. The article is devoted to the study of the image of the Kalmyks created by foreign travelers of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century. There are no special imagological studies in Kalmyk historical science, which gives relevance to this work. The article assumes the solution of the following tasks: 1) identification of the factors that led to the perception of Kalmyks by observers, 2) description of the means used by foreign travelers, recreating in travelogues the main features of the image of Kalmyks, and their worldview, which influenced the construction of this image, 3) assessment of the socio-cultural consequences that arose as a result of the formation of ethnic stereotypes about Kalmyks. In the XVII century. Kalmyks, having migrated from Dzungaria, mastered the steppe expanses on the right bank of the Volga, created a khanate in Russia. Sherti (oath of allegiance Ц E. D.) formalized their entry into Russia. Although the nomads turned out to be part of the European peoples, they retained their traditional way of life, remaining on the periphery of the Buddhist world. The religious affiliation of the Kalmyks to this world, according to researchers, complicated their relations with both the Islamic community and the Christian community in a cultural and political sense [1]. Kalmyk uluses were initially little attractive to travelers. Given the specific goals of foreigners in the Kalmyk steppe, which many visited on their way to Persia and back, their observations about the Kalmyks differ from those given in the works of Russian administrators. The travelers described the appearance, dwelling, behavioral characteristics of the Kalmyks and the relationship between them from the perspective of their culture. Materials and methods. The theoretical and methodological basis of this work was the work of researchers on the images and representations of different civilizations relative to each other. Historical imagology, which studies images and stereotypes of perception of phenomena and people that existed in the past, as a branch of historical anthropology was developed in the second half of the last century. The work "Asia in the Formation of Europe" by D. F. Lacha [2], became one of the first studies of the influence of Asia on Western culture. The author showed how the images of Asia influenced European civilization in the XVI-XVIII centuries. E. Sayd in the book "Oriental Studies" [3] came to the conclusion that the comparative approach to the study of the East led Western science to justify colonialism. In the article "The Orient of Travelers and Scientists: between dictionary definition and living thought", Sayd emphasizes that "the traditional oppositions "Europe Ч Asia" or "West Ч East" are used by Orientalists only to describe all conceivable human diversity using extremely generalized labels, to reduce it to one or two simplified summary abstractions" [4]. This position caused a discussion in the scientific community and contributed to further study of the problem of the emergence of knowledge about the "other". I. Neumann in the book "Using the Other". Images of the East in the formation of European identities" applied historical and modern material to assess the image of the "Other" in European and Russian discourse. Neumann explained the importance of this image as follows: without it, "the subject cannot have knowledge about himself or the world, since knowledge is created in a discourse where consciousnesses meet." [5, p. 40]. Y. L. Slezkin, exploring the problem of the image of the "Other" on the Russian material, drew attention to the importance of separating ethnic and ethnographic representations: "before describing peoples, a traveler must decide where one nation ends and another begins" [6, p. 173]. In Russian science at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s, I. S. Cohn expressed the opinion that the concept of "national character", which arose in the descriptive literature about travel at the level of everyday consciousness, is designed to "express the specifics of the lifestyle of a particular people" and involves comparison and fixation of differences. He stressed: "those features that are perceived as specific features of a national character are determined not by natural abilities, but by differences in value orientations formed as a result of certain historical conditions and cultural influences, as derivatives of history and changing with it" [7, p. 319]. Imagological research in Russia began at the turn of the 1980s and 90s.† Within the framework of the interdisciplinary scientific seminar "Russia and the World: problems of mutual perception", a series of collective works was published on various aspects of the formation and interaction of foreign cultural images, which understood all categories of ideas about the outside world [8]. The interdisciplinary nature of this study has determined the interest in the experience accumulated in Russian science in studying the mechanisms of perception of the "other" [9]. Travelogues of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century were chosen as the material for constructing the image of the Kalmyks by observers. They allow taking into account the subjective moment of perception, revealing the problem of historical reality and its representation in a historical source. Let's agree with L. P. Repina, a characteristic feature of the "travel literature" is "that the description of the observed single case is presented as typical for this culture" [10]. Despite the brevity of the remarks related to the lack of travel time, travelogues, fixing the picture of the "alien" world, reflect common simplified attitudes. This allows us to study the peculiarities of the worldview of the authors themselves, the proportion of the subjective in the presentation, and using narrative analysis to discover the meaning of the text. The historical discourse of otherness is revealed using the method of semiotics. Results. Travelogues by European and Ottoman authors of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century are selected for analysis. An important factor influencing the perception of Kalmyks by observers was their goals. The travelers did not set a task specifically to be in the Kalmyk steppe. The lower reaches of the Volga attracted foreigners in connection with the prospects of developing trade through Astrakhan with the countries of the East and the search for raw materials. The German traveler, geographer and historian Adam Olearius (1599-1671) was an adviser to the embassy that Duke Frederick III of Schleswig-Holstein sent in 1634 to Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich and the Persian Shah Sefi I. In 1635, Olearius descended along the rivers Moscow and Oka to the Volga, then down and further along the Caspian Sea to Persia. In 1639, the Holstein embassy returned to Moscow. Olearius' travel notes formed the basis of his work "Description of the journey of the Holstein Embassy to Muscovy and Persia" [11]. The author's acquaintance with the Kalmyks was fragmentary.

A young lawyer Nicolaas Witsen (1641-1717) from an Amsterdam merchant family, who received a doctor of law degree, came to Russia to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1664 as part of the embassy of J. Boreil, whose task was to promote the trade interests of the Netherlands. During the trip, Witsen kept a diary [12], which, along with the information collected later, formed the basis of the book "Northern and Eastern Tartary" [13]. In Moscow, the observer met the grandson of Taisha (Prince Ц E. D.) Daichin Jalba. The latter was a cousin of the Kalmyk Khan Ayuki, who, in an effort to get rid of a rival, accused Jalba of treason and sent him to amanats (hostages Ц E. D.). With the help of Jalba, the traveler marked on his map of Northern and Eastern Tartary the place where the Kalmyks' uluses roamed.† Witsen's informants were Taishi Monchak's ambassadors who arrived in Moscow and Kalmyk servants from the embassy. Witsen also received reports about Kalmyks from Georgia from Europeans living there. The observer was not in the Kalmyk steppe, but questioned his informants in detail about their homeland, culture, customs, and kept careful records. Dutch sailing master Jan Jansen Streis (1630-1694), who was employed in the Russian service in Amsterdam, was an adventurer. In 1668, Streis, who had previously traveled to Africa and Japan, arrived in Russia. He crossed the country from the Baltic Sea to Astrakhan. The Dutchman sailed down the Volga on the first Russian warship, the Eagle, presented by the Moscow government. In Astrakhan in 1669, he met with S. Razin, who had returned from the "zipun campaign". After escaping from Razin, Streis reached Dagestan, where he was captured by local tribes and sold into slavery in Persia. After being released from captivity in Shamakhi, Streis reached the East Indies, was accepted into the service of the East India Company and was able to return to Holland. As part of the Dutch embassy, Streisu subsequently visited Russia again. He collected his travel notes in the book "Three Journeys", in which he outlined the customs and customs of the peoples of Muscovy and the East [14]. The Dutchman observed Kalmyks during his voyage along the Volga, his stay in Astrakhan, and his captivity. Evlia Celebi (1611-1682), historian and writer who devoted 40 years of his life to travel. Seeing the prophet in a dream, the young Evliya exclaimed with excitement: "seyahat" (journey Ц E.D.). His father advised him to go on a journey and describe the miracles that he would see. The Travel Book written by the author contains extensive material about the life and lifestyle of the peoples of the Volga region, the Don region and the North Caucasus [15]. Celebi was the first Ottoman observer to obtain detailed information about the Kalmyks. In 1666-1667, he visited the Kalmyks' nomads, where he communicated with the Taish Daichin and Monchak and commoners. The Dutch painter Cornelius de Bruin (1652-1727), author of popular travel sketches, came to Russia in 1701. After staying in Moscow for almost a year, he met Peter I, thanks to which he painted portraits of the tsar and other members of his family. In 1703, he left Moscow to continue his journey down the Moskva River, the Oka and the Volga to Astrakhan, then across the Caspian Sea to Persia. De Bruin also visited India, Ceylon, Java. His book "Journey through Muscovy to Persia and India", compiled on the basis of travel notes, contains sketches made by the painter in places past which his ship sailed [16]. The painter observed Kalmyks in Astrakhan and Saratov. The Scotsman John Bell (1691-1780) wished to come to Russia in 1714 to make a trip to Persia. Thanks to the patronage of Peter the Great's life physician R. K. Areskin, he got the opportunity to go to Persia at the embassy of A. P. Volynsky as a doctor. In 1715, the traveler left St. Petersburg down the Volga, making stops in the Volga cities, where he observed the Kalmyks. In 1719-1721 . Bell visited China as part of the Russian embassy, in 1722-1723 he was a member of Peter I's Persian campaign as a staff doctor, and in 1737-1738 he visited the Ottoman Empire. Bell's daily notes were later published under the title "Journey from St. Petersburg to various parts of Asia" [17]. As a witness, he described the meeting of Emperor Peter I with the Kalmyk Khan Ayuka in 1722. Between 1722 and 1725, an unknown European author traveled and lived in Russia among the peoples he described, whose manuscript is kept in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. This foreigner observed the Kalmyks and left a description of their life [18]. The Prussian physician I. J. Lerche came to Russia in 1731, joined the military service and was appointed chief physician in the Astrakhan corps. In the spring of 1732, he observed the Kalmyks and described their way of life in a note that was published by G. F. Miller in volume 4 of the Collection of Russian History. Lerche took part in a military campaign, during which he visited the Caspian region (1733-1735), in the wars with Turkey (1735-1739) and Sweden (1741-1743). In 1746-1747 he accompanied the Russian embassy to Persia. Lerche described a campaign to the Crimea, containing evidence of its Kalmyk participants [19]. For foreigners, the journey was an escape from everyday life, a collision with the other. Observers sailed along the Volga past outposts created to protect against Kalmyks attacks, communicated with government representatives, which could not but affect the formation of the image of the Kalmyks. They considered the tendency to aggression and conflict to be a characteristic feature of the Kalmyks. Witsen, according to his informant from Georgia, assures that the Kalmyks are "very belligerent, and other Tartars are afraid of them" [13, p. 389]. Streis and Olearius write about the thefts of people and livestock and the constant hostility of the Kalmyks and Nogai Tatars, who in winter are given weapons by the Astrakhan governor to protect them from raids, which they must return at the beginning of summer [11, p. 349, 14, p. 86]." Olearius notes that in Saratov "only Streltsy live, who are under the control of the governor and colonel and are obliged to protect the country from the Tatars, who are called Kalmyks among them: they live from here all the way to the Caspian Sea and the Yaika River and quite often raid up the Volga" [11, p. 434]. According to Streis, the neighborhood of Cossacks, Tatars, namely Kalmyks, forces it to contain a strong garrison of Streltsy led by the voivode [14, p. 79]. De Bruin reports that Kalmyk Tatars are raiding from Syzran all the way to Kazan and capturing people and cattle.† He mentions that the city of Chernoyar is "inhabited only by soldiers who are stationed here to repel and protect against raids by Kalmyk Tatars, who often capture herds of natives and retire with them to Samara itself" [16, pp. 175, 183]. Lerche notes that in the space from Astrakhan to Tsaritsyn, outposts are set up every 30-40 versts, where Cossacks and Astrakhan Tatars serve to protect against Kalmyks. He cites the example of the Enotayev fortress, the construction of which was started by the Astrakhan governor V. N. Tatishchev "mostly because of the Kalmyks" [19, p. 244]. As we can see, the conclusion about the militancy of the Kalmyks was made by observers before coming into direct contact with them. This suggests that travelogues are more about the perception of realities than the realities of everyday life themselves. Observers note the hostility of the neighbors towards the Kalmyks. Streis writes that Kalmyks and Nogais "almost always wage war and are almost engaged in stealing from each other not only cattle, but also people who are sent weekly to trade in the markets in Astrakhan" [14, p. 80], De Bruin testified about the attack of Cossacks on the Kalmyk ruler [16, p. 230].

The Kalmyk steppe was viewed by foreign travelers as a backward suburb, and its inhabitants as barbarians who "lead a wild lifestyle, fight among themselves and with neighbors, or have fun" [13, p. 356]. We have chosen the concepts used in travelogues to refer to Kalmyks. Most often they are called "Kalmyk Tatars", they claim that they originated from the Tatars. Celebi recalls Arabic books in which the Crimean people were warned about the danger posed by "a people with small eyes, originating from yourself, that is, beware of the Kalmyks people" [15, p. 547]. N. Witsen separates Kalmyks and Tatars, emphasizes that neighboring peoples consider Kalmyks Tatars, but they are "offended if they are called that, and even often spit upon hearing this name [13, p. 285]. He connects the origin of the word "kalmak" with the long hair, "braids" worn by these people [13, p. 361]. The image of "Others" is created by travelers using linguistic means. Streis calls the Kalmyks "ludocrats" [14, p. 80], an unknown author calls them a "barbaric nation", a "wild people", for Chelebi they are "a crowd of people worthy of neglect, cursed, unclean, indomitable." Celebi uses specific vocabulary in relation to Kalmyks: "neglected and cursed, robber and insignificant crowd", "unclean people", "dirty Kalmyks", "kafirs" (infidels Ц E. D.), "cursed", "lost", "beni-asfar" (tribe of yellow-faced Ц E. D.) [15, p. 547]. The negative image is based on medieval customs of describing "Others". Thus, Celebi relies on the Ottoman tradition of using rhymed pejorative epithets in relation to other peoples, for example, "Kalmyks Ч "evil created" (Kalmuk Ч bed makhluk)" [20, p. 6]. The linguistic techniques of foreign travelers speak of a dualistic concept of a world where "one's own" are the forces of Good, "others" are the forces of Evil. "Strangers" are opposed by "their own" Ц "enlightened people". The antithesis of "friends and strangers" is evaluative, emotionally colored, therefore, Kalmyks for travelogue authors are "the most evil of all Tatars" [12, p. 711], "uglier and scarier than all people", [14, p. 79], "a cursed tribe that all peoples are afraid of" [15, p. 544]. Bell emphasizes: "They do not have in their language any of those terrible oaths, which are very common among enlightened peoples" [17, p. 222]. The feeling of superiority of one's own culture over the culture of "Others" does not allow observers to be objective. In creating the image of the "Other", an important place is occupied by the visual characteristics of appearance. Kalmyks, according to an unknown observer, have a terrible appearance: a wide and flat face, a flattened nose, small black deep-set and inconspicuous eyes, a thin beard, unkempt long locks [18]. According to Streis, all Kalmyks look the same, almost all have "a face a foot square, a nose proportionally wide, but so little protrudes and stands out among the cheeks that ten steps away you can bet that they don't have it at all. The mouth and eyes are extremely large, and all the features are extremely ugly. Their hair is shaved, except for one braid, which flutters on their heads" [14, p.79]. De Bruin drew attention to the flat and wide faces of the Kalmyks, puffy cheeks and oblong eyes [16, p. 211]. According to Bell's description, Kalmyks have a wide face, a flat nose, small black eyes, but very sharp" that they all "shave their heads, turning off one strand of hair, which they braid and wear backwards" [17, p. 220]. Celebi assures that male Kalmyks have neither eyebrows nor eyelashes, and their faces are flat like plates [17, p. 550]. Witsen writes that Kalmyks "shave their beard, leaving only a small moustache above their lips, which looks ugly" [13, p. 390]. These visual characteristics indicate that observers consider an appearance that does not meet the standards of their own cultural tradition to be terrible. However, as ugly as the men's faces seemed to the observers, the women's faces were just as pretty. Celebi noted that the steppe women did not neglect cosmetics: they brightly tinted their eyes with antimony, and smelled resin behind the ears instead of musk [15, p. 551]. According to the norms of "their" culture, travelers interpret the body as a text. They note low stature, corpulence, stockiness, and extreme strength [16, p. 211]. This sign reads as belonging to the lower strata engaged in hard physical labor. A body that contradicts the standards of its own culture causes a repulsive reaction, provokes ridicule: "Their necks are very short, their heads connect directly with their shoulders. At the same time, the necks are as thick as the necks of wolves. Their shoulders are all so wide that one person can sit on each one. They have broad shoulders and hips. The lower part of the body is like a large basket; their necks are short, their thighs and shins are long. And the thin bones inside them are crooked. When they get on a horse, their crooked legs wrap around the horse's belly. That's what their stature and composition are" [15, p. 549]. In the description of Chelebi, nomads have a fat, well-fed body, pumpkin-like heads, large palms and ears, short and thick necks and forearms, cucumber-like fingers, large molars of Kalmyks like camel teeth. They do not know dental diseases because they have not eaten hot food all their lives. Their clothes and heads smell bad [15, p. 550].† Describing an alien world on the principle of contrast, Streis and Witsen write that Kalmyks move exclusively on horseback and are always armed with sabers, arrows, a bow and long knives. They use "a few guns" to hunt birds and game. Heavy gait, curvature of the legs, apparent lameness, in Witsen's explanation, are associated with continuous riding [12, p. 123]. The observer compares his own and others' riding methods: "Sitting on a horse, they do not hold the bridle with their hands, like Europeans." In winter, when there is snow, the author writes, "in many places of the Kalmak deserts, people ride on land on sleds with sails" [13, pp. 361-362]. In creating the image of the Kalmyks, color was important, which was an instrument of symbolization. Witsen describes in his diary that the Kalmyks are "ugly, their eyes are small, their faces are flat, yellowish in color" [12, p. 103]. The ambassadors of taisha Monchak are "people of small stature, dense and yellow-brown in color; their faces are flat, with wide cheekbones; their eyes are small, black and narrowed; their head is shaved, only a braid hangs from the back of the crown", who constantly smoke a pipe and assure that they cannot live without it, taisha Jalba Ч "the man is very ugly, brownish-yellow, with a flat broad face, his forehead is high, black hair, a braid behind" [12, pp. 123-124]. The perception of color is essential, because since the beginning of the XII century in the Christian tradition, yellow is considered the color of Judas, the color of lies and betrayal. Celebi calls the Kalmyks "yellow geeks" [15]. Yellow for Muslims symbolizes, on the one hand, the sun, gold, joy, on the other, it is a sign of gastric diseases. Bell calls the Kalmyks black Tatars and notes that they are swarthy [17, p. 221]. Witsen writes that Kalmyks are "blackish, ugly, with flat noses, and scary to look at" [13, p. 389]. In Christian culture, black is associated with sin and darkness, so the depiction of Kalmyks by blacks has a moral symbolism.

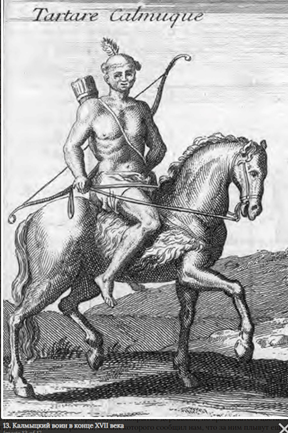

To emphasize the "ugliness" of the face of the Gentiles, which, according to the aesthetic dichotomy, indicates the ugliness of the soul, a narrative technique such as comparison is used. Streis believes that "even Hottentots and ugly Moors have more friendly and beautiful faces than they do." Nogai and Crimean Tatars, according to him, are "angels in comparison with Kalmyks, whose appearance has something terrible." He also compares Kalmyks and Dagestani Tatars and writes that the latter's faces are not as quadrangular as those of Kalmyk or Crimean Tatars" [14, p. 86]. Witsen assures that "you will not find a more ugly people than the Kalmaks in all of Asia: the face is flat and wide, with about five fingers between the eyes" [13, p. 381]. If the visual image of the Kalmyks, created by Europeans in the first half of the XVIII century, shows a transition to realism, then the Ottoman traveler is characterized by a desire to visualize this image with the help of symbolism and fantasy. He explains the narrow slit of the Kalmyks' eyes by the absence of "salt mines in the local valleys."† However, this compensates for visual acuity, "they will thread a needle even at night." Celebi suggests that at birth, "their eyes open within a week, like puppies; some eyes do not open, and then they are opened by cutting through with a razor, while lightly rubbing with salt" [15, p. 849]. The next important characteristic of otherness is clothing. Witsen wrote that Kalmyks dress in rough skins of sheep and other animals, "rarely in embroidered caftans made from the skins of various wild animals. They wear large rings in their ears, sometimes threaded through the nose" [12, p. 154]. De Bruin notes that the Kalmyks' clothing, depending on the time of year, consisted of a caftan and sheep's skin [16, p. 229]. Bell remembered the simplicity of Kalmyks men's clothing, which consists of a sheepskin caftan belted with a sash, a small round hat lined with fur, with a silk red brush, leather or canvas ports and boots. Women's clothes are more elegant, the caftans of the Kalmyks are longer and trimmed with patches of different colors. Bell noticed that Kalmyks wear earrings and braid their hair, and noble women wear a silk dress in summer [17, p. 220]. Celebi saw women wearing headdresses decorated with many tassels made of scraps of silk, embroidered caftans made of Chinese colored calico, felt chakshires (trousers Ц E. D.) and pabuchi (slippers Ц E. D.) made of pigskin [15, p. 549]. Witsen writes that Kalmyks have rings in their ears and nose [13, p. 362]. Travelogue authors judge social differences by their clothes. De Bruin pointed out that some Kalmyks have "hats, doublets and caftans made of simple cloth, under which ports were visible, but without shirts" [16, p. 229]. Celebi described the ceremonial clothes of the Kalmyk taish Daichin and Monchak. Daichin met an Ottoman traveler in a fur coat made of the skin of a spotted fallow deer turned outwards, under which there was a caftan made of the skin of a baby fallow deer, but with the fur inside. Taishi's fur coat was belted with a horsehide belt. He was wearing blue felt chak-shires. On Daichin's head was a hat trimmed with a fox, with a top made of white leather, on the top of which were tassels made of multicolored scraps of silk, and between them was a drilled diamond the size of an egg. Daichin's son Monchak was similarly dressed, with the exception of tassels and a diamond on his cap [15, p. 548]. Bell compiled a description of the clothes of the wife and daughter of the Kalmyk Khan Ayuki: "Both mother and daughter were dressed in long dresses of their Persian expensive cloth, and in round sable-trimmed caps according to their custom" [17, p. 231]. Travelers negatively emphasize the nakedness of nomads. Kalmyks, in Witsen's description, lead "an almost animal lifestyle, they go bare-chested in summer", and "often bare the upper part of their bodies in battles" [13, p. 364]. K. de Bruin depicted the Kalmyk warrior practically naked (Fig. 1). When meeting Prince Jalba, Witsen felt ashamed when in a room where it was hot, the Kalmyk "took off his fur coat, bared his chest and shamelessly itched in front of us; his body and face were covered with pimples like a plucked goose" [12, c. 125]. The negative is associated with the Christian tradition, which condemns nudity, teaches that clothes are a virtue, a sinner in the eyes of God is naked and ugly.

Fig. 1. Kalmyk warrior at the end of the XVII century. Fig. K. de Bruin What does the visual image of Kalmyk created by de Bruin say about its author? The artist chose not a household plot, but a military one. In the context of the war against the Gentiles, which occupies an important place in the worldview of Europeans, such an image says that the image of the Kalmyks is dominated by the idea of their aggressiveness. In the drawing we see a huge figure of a warrior on a horse. The large size of the drawing indicates a high self-esteem, expansiveness of the artist, a tendency to vanity and arrogance. The bold lines of the drawing symbolize increased anxiety. The huge figure of the warrior is drawn disproportionately in relation to the horse, which indicates a feeling of great strength. The visual sign of the barbarian is nudity. So, the alien world is described according to the principle of contrast. Men's braids are an indispensable attribute of the image of a gentile. Prince Jalba, Witsen's interlocutor in Moscow, was distinguished by his "red-browed" skin, flat and wide face, high forehead, black hair "hanging in a braid from behind." The observer noted that Kalmyks wear long braids hanging back, and "if they don't have hair, they borrow women's braids or weave them into their horsehair, which is easy for them to do, since their hair is quite similar to horsehair." The envoys of Taishi Monchak, Witsen's other interlocutors, had shaved voices, with the exception of "a braid hanging from the top of their heads." De Bruin writes that the hair of Kalmyk boys is as well braided as that of women "in two plaits" [16, p. 229]. According to Celebi, there is no hair on the body of nomads, and beards are very rare, which is a sign of infamy for a Muslim who cared for his beard with care and care. Observers compare "their own" and "others'" rules of etiquette. Witsen writes that Taisha Jalba did not bare his head when meeting him. He concluded that the Kalmyks "do not bare their heads either during worship or for greeting" [13, p. 362]. At the same time, the observer noted that the Kalmyks are familiar with the rituals of greeting and farewell: "At parting, Taiji took us by the hands, as well as at our arrival; he kindly asked that we come again tomorrow" [12, p. 126]. He also reports on the unusual table etiquette for Europeans: "While eating, they sit on the ground like tailors and can get up quickly without touching the ground with their hands" [13, p. 363].

The main criterion of otherness in travelers' travelogues was religion. Observers call the Kalmyks pagans, believe that the Kalmyk people "are immersed in the darkness of idolatry, are at a lower level of education than the Astrakhan Tatars" [17, p. 222]. An unknown author writes that the nomads worship terrible idols similar to them, decorated with gold and silver, which the priests always carry with them in boxes [18]. In describing religion, the authors' rhetoric is based on inversion. Thus, Celebi calls Kalmyks kafirs, because they do not know "what resurrection and resurrection, weight and scales, heaven, hell and purgatory are, what the Four books and the prophet, religious precepts and the Sunnah are Ч they do not know at all." [15, p. 551]. The Ottoman author explains that "one [part of] the people are idolaters. The religion of others is the belief in reincarnation. Another tribe worships fire. Another group is sun worshippers. One branch worships the earth. Another group is moon worshippers. Finally, one tribe worships a cow." Witsen writes that Kalmyks pray to burkhans, gold, silver and copper sculptural images of the Dalai Lama, to whom "they render divine honors, and whom the Kalmyks revere more than the Chinese. After death, he allegedly returns to the woman's body and is reborn, which they firmly believe." Witsen notes that his interlocutor "prays to God, who is above; he did not know about Christ or Mohammed" [13, p. 355]. From the position of superiority of their own culture, travelers describe the religious rites of the Gentiles: "When the Kalmaks pray, they pinch their fingers to spite the devilЕWhen Kalmaks pronounce an oath, they sometimes cut a pig in half and lick the blood from a knife, and sometimes they cut a black dog with a sword and, licking its blood from the sword, say a few words" [13, p. 361]. Witsen records the way of prayer of the Kalmyk owner: "Under his right hand hung a box on a leather strap, where he kept a scroll of his prayers, which he took out daily, and holding it in his hands directly in front of his head, kneeling, bowed to the ground 9 times <...> He had with him a strange-looking rosary in the form of small beads, by which he counted out prayers to God" [12, pp. 125-126]. He shows Jalba his way of prayer: "I showed: I put my hands together and knelt down." These descriptions profane the religion and rituals of the nomads. Observers note that the Kalmyks do not have the usual stone temples, but "strange large felt churches with two doors through which light passes. Instead of a bell, they beat basins" [13, p. 355]. The authors contrast their faith and civilization with the Gentiles. According to Witsen, co-belief has a positive effect on morality. He writes about a group of Kalmyk Tatars roaming around Astrakhan, who are "more moral, have some kind of religion: and some of them are Turkish-Mohammedans." Russian Russian indicates the path of enlightenment of the Kalmyk taishi: "Maybe he will accept the Russian faith, icons are already hanging in his room, he already knows how to be baptized, and then he will become a Russian courtier, like other baptized Tatar princes" [12, p. 125]. In the image of the Kalmyks, an important place is occupied by the main feature of their daily way of life Ц a nomadic lifestyle: they "do not live in cities, villages, or houses, but settle in detachments or nomads in small huts on one or another fat pasture. When their horses, camels, cows and small cattle are stripped and devoured clean, they rise from this place and move to another pasture."† [13, p. 276] Kalmyks "do not sow and do not reap", "ride and ride everywhere on camels", "with a lack of grass (in pastures) they (hordes) meet, then they fight over it, the winner kills the defeated or turns prisoners into slavery", "they do not have permanent housing, they wander from pasture to pasture", they do not harvest hay, but "in winter cattle (among them there are sheep with tails weighing three to four pounds and more) feeds on bushes and branches or scratches unspoiled grass out from under the snow" [13, p. 383]. As you can see, in creating the image of Kalmyks as "Others", foreigners often use such a technique as inversion. The dwelling of the nomads has an unusual conical shape: "they are built of poles inclined one to the other, which have an opening at the top for receiving light and for releasing smoke. These poles are fixed across with holes, from four to six feet long, which are nailed with nails; and all this is covered with thick felt and cloth." According to Witsen, Kalmyks make felt for their caravans by twisting cow's wool into thick pieces. There is a light hole at the top of the caravan that can be closed, it is warm in them, people are protected from wind, rain and snow. Household goods, especially clothes and weapons, are placed on the walls of the tents. This description clearly shows the divergence of cultural traditions and customs of travelers and nomads. Travelers evaluate their own place of residence as the center of the universe, therefore, the "friend-foe" opposition is built on the basis of the category of space. Celebi mentions the Heyhat steppe (Desht-i-Kipchak Ц E. D.) as a place of Kalmyks' nomadism. He says that there is no water or trees in Heyhat, but it is rich in grass, so "no matter how many cattle they eat, it does not decrease, like drops in the sea and the smallest particles of the sun." There is so much grass that it hides horses, camels and cows [15, p. 547]. In Witsen's description, the Kalmyk steppe is an infertile country with sandy and salty land. The place of nomadism in travel notes generally seems to be a space remote from civilization. Observers explain the simplicity of the nomads' life by their way of life: "Their food is horses, their clothes are horse skins; they even have shirts and trousers made of skins" [15, pp. 569-570]. There is a connection between the poverty of the steppe nature and the wild lifestyle. The history of animals as part of cultural history is being developed in narratives. Travelers write about doubleЦhumped camels, large sheep with coarse and coarse hair, thick tails heavy with fat, water carriers and a bird baba (pelican - E. D.) in the Caspian Sea region, wild donkeys with large horns [13, p. 359]. There are mentions of a wonderful Kalmyks plant Ц "boranich", growing out of the ground, "these are the skins of unborn sheep, which were taken out of the mother's belly, which greatly increases their price, because the uterus must die with it" [13, p. 357]. In Chelebi's description, Kalmyk horses are "very fat, squat, shortЧlegged, with a rump like a bull, and they have a groove on each hoof, so that their hooves are as if forked, but still not paired. Their legs are so thick, they look like round bread. And their bellies almost reach the ground. Their chests and backs are very wide. And the necks are short, like the necks of bulls" [15, p. 561].

Among the everyday scenes described by travelers, those that reproduce the most common activities prevail: migration, trade, hunting. According to Witsen and Celebi, the Kalmyks do not know money, but trade by exchange. Streis observed the Kalmyks' money trade in Astrakhan, de Bruin in Saratov. They noted that the nomads exchanged their livestock and livestock products for various kinds of supplies and goods, rice, bread and linen. Bell visited a fair near Saratov, where 500 to 600 Kalmyks arrived, camped on the opposite side of the Volga in caravans. He describes the species composition of the main wealth of the Kalmyks Ц cattle: dromedary camels, cows, horses and fat-tailed sheep. The traveler notes that Kalmyk horses are hardy, they are sold at fairs for 16 rubles, the price of pacers can be higher. He observed how Bukhara sheepskin was sold from 25 to 30 rubles, and Kalmyk sheepskin for 50 kopecks, because "the wool on them is tougher, does not have so much gloss, and at the same time their dressing is not so good." Obviously, we are talking about steppe merlushki (lambs' skins obtained from coarseЦhaired fat-tailed sheep - E. D.). Having received money from the sale of livestock, Kalmyks buy bread and cloth "to dress their wives" [17, p. 221]. Bell notes that the Kalmyks have achieved perfection in falconry and are great hunters of "hares. "They kill Drokhv (bustards Ц E. V.) with arrows," he writes, "seizing the time when these birds are eating, and galloping towards them at full speed. As they are very heavy and do not rise soon, these hunters have time to approach them and shoot them" [17, p. 226]. Other types of activity, according to him, are considered "the most brutal slavery", therefore, if they wish evil to a person, then "they send such a person to live elsewhere, and so that he works like a Russian" [17, p. 222]. Travelers note the lack of crafts among the nomads, except for the production of weapons, and the underdevelopment of fishing due to the fact that they "have neither flax nor hemp and, therefore, no threads for weaving nets" [13, p. 359]. The nomads' food preferences are evidence of otherness. According to Streis's remark, the Kalmyks' favorite food is dried horse meat. It is not boiled or fried, but only put under the saddle, softening "through the warmth of the horse" [14, p. 80]. Doctor Bell, on the contrary, believes that only extreme need forces Kalmyks to eat raw meat, they eat fried, dried and smoked horse meat. He tasted the cooked meat and noticed that it was "not as unpleasant as people think" [17, p. 222]. Lerche, in the Crimean campaign of 1738, witnessed how in the Northern Azov region the Kalmyks pulled a horse out of the river in March, which drowned at the beginning of winter, decided that "it was still fat for food, so they very soon divided it among themselves", as they ate beavers at another halt [19, p. 120]. In Witsen's description, Kalmyks "eat everything, even snakes and other offspring, which we are afraid of" [13, p. 389]. An unknown author writes that they feed on rats, cats and in general everything that comes across, raw, without bread, which they do not know at all [18]. According to Celebi, Kalmyks "drink mare's and camel's milk, buzu and talkan", eat meat of camels, cows, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, wild camels, wild horses, wild buffaloes and wild donkeys [15, p. 549]. Bell writes that during migrations, Kalmyks carry only cheese, from sour and dried milk they make "small pellets, which are dissolved in water and drunk" [17, p. 222]. Witsen and Celebi are convinced that Kalmyks do not know bread, therefore, "if someone has slaves from there, and they need to be gradually taught to eat bread, otherwise they get sick from it [13, p. 368]. De Bruin, sailing along the Volga, threw bread into the water from the ship, for which the Kalmyks rushed to swim [16, p. 229]. The criterion for distinguishing between "one's own" and "others'" is morals. Witsen condemns human trafficking in Kalmyk villages, believes that love is poorly developed among Kalmyks, mothers sell infants, and relatives of each other without compassion [13, p. 361]. An unknown author notes the Kalmyks' penchant for drunkenness [18, p. 356]. Celebi mistakenly attributed ritual cannibalism to the nomads. The observer assures that the captured Turks and Crimean Tatars are boiled and eaten by the Kalmyks. He believes that the same fate awaits their shahs [15, p. 551]. Witsen is more realistic in describing the funeral rite: "They burn the bodies of deceased princes and great lords, and bury the bones and ashes. They believe that they will come to life again. But where they go, this kalmak could tell me almost nothing, except that they believe that the souls of people are transported to the end of heaven and remain there to roam. The bodies of ordinary people are buried or thrown into the water" [13, p. 358]. Such a sphere of legal relations as family and marriage has attracted the attention of foreigners, where travelers find a lot of evidence of otherness. They speak with condemnation about polygamy of the Kalmyks. †Witsen notes that the number of wives depends not only on desires, but also on material possibilities, therefore "among the common people there are rarely more than three, four or five wives" [13, p. 347]. Marriage among Kalmyks can be concluded outside the third degree of kinship. However, after the death of a brother, another brother can marry his widow, "whether she has children or not. And a son can also marry his stepmother, whether she had children with his father or not" [13, p. 348]. As an example, he cites Taisha Monchak, who married his stepmother [13, p. 362]. Celebi writes that Kalmyk men do not know what it means to woo a woman: "they quickly resort to lots and take [her]" [15, p. 552]. The traveler also records pre-wedding events unusual for Europeans ("When they get married, they buy wives for horses: whoever gives more will get it. Everyone takes as many wives as he wants and can let them go, but then women cannot [remarry]") and wedding customs ("Their wedding consists in the fact that the priest blesses them and solemnly calls for consent") [12, p. 126]. Bell writes about the extreme chastity of Kalmyk women who are "incapable of frivolity and do not know what adultery is" [17, p. 220]. The traveler's space is limited by his linguistic capabilities, so the observers used the services of translators. Travelogues contain value judgments about the Kalmyks language. Witsen notes that Kalmyk's speech "sounds very strange: he cackles like a turkey, and when he listens attentively to the conversation, he snores like a pig" [12, p. 124]. Celebi assures that "I have not heard such a terrible language like the barking of Samson dogs Ч with the guttural pronunciation of the sounds "lam", "mim", "ha" and "nun" Ч as difficult as the language of the Kalmyks." He writes that the Kalmyks have twelve languages, so they do not understand each other [15, p. 560].

Witsen wrote down several generic names and explained the meaning of the name "Taishi Yalba Dois": "The first word means prince, the second is his name, and the third is his father's name. He changed his name in his youth because he was often ill and, believing that the cause of the disease was the name, changed it" [12, p. 125]. The name of Khan Ayuki means "honorable". The names of the advisers are mentioned: Taehe, Areson, Mirgin and Tallier, and the Derbet taishi Solom-Tseren [13, p. 343]. They contain errors related to the difficulties of transcription for a European. It is not clear whether Witsen was trying to "translate" these names, which are foreign to European ears, into a language understandable to the reader. We believe that he names other people's realities in order to give his work credibility. After seeing Kalmyk's prayer book, Witsen noticed that "they read and write like ours" [12, p. 125]. Using the comparison technique is a way of understanding otherness. Everything that the "Other" has corresponds to "His" seems to be positive. The travelogue of Celebi is characterized by the medieval Ottoman tradition of depicting the "Other" using representations of miracles. The narrative elements characteristic of the rhetoric of otherness are found in his book, which describes the effects of fog, the witchcraft of the "cursed Kalmyks" Ц yaishylyk, from which the travelers and the warriors surrounding them lost their minds. Elsewhere in the book, the traveler reports that Kalmyks do not have diseases, so they live for 200, 250 and 300 years [15, pp. 549, 553]. To give credibility to his story, he mentions a meeting with Kalmyks 270 and 309 years old. Celebi tells about the Kalmyks' pilgrimage to the Kaaba. Describing this wonderful place, he writes that a woman who gets pregnant there lives 500 years and gives birth to immortal children. In the valley of the Kaaba, it is as bright at night as during the day, in the vicinity in a magical garden a river flows, the waters of which turn an old man into a young one [15, pp. 554-563]. Witsen assures that the steppe women are brave as men, and incorrectly assumes that the stories about Amazons come from Kalmyks [13, p. 348]. The meaning of the observers' narrative is simple: there are amazing miracles in the world of "Others". The exclusion of outsiders from the ordinary is not always revealed through denial. The authors describe positive qualities: the diligence of the Kalmyks, who make "very good servants and there are no such works that they would not demolish, if only they treated them kindly" [17, p. 220]. An important trait of nomads is their love of freedom and aversion to coercion and captivity. They believe in virtue, which "makes a person happy, and vice poor; and when someone encourages them to do some injustice, they respond with such a proverb that "even a sharp knife cannot cut without a handle" [16, p. 222]. Among them there is no slander and slander, empty talk and swearing, insults and suspicion, arrogance and malice, hostility towards each other, they are not characterized by lies and deception [15, p. 551]. Bell admits at the end of the trip that the ideas about the hostility of the Kalmyks are exaggerated [17, p. 223]. When correlating the lives of "Others" with one's own model, mental fluctuations occur, therefore, vices and virtues opposing them are located in the zone of barbarism. †The negative meaning is compensated through further reference to the kindness, simplicity and hospitality of the Kalmyks. Describing Kalmyks as barbarians, observers make an exception for the traditional Kalmyk elite. Bell writes about the beauty of the khan's daughter Ayuki: "she had a very fair complexion in her face, and her hair was as black as agate. They were tied behind her and lay on her shoulders" [17, p. 231]. The Kalmyks did not perceive outsiders in an ordinary light. De Bruin writes that the steppe people he met "looked at my dress with surprise, as it seemed to them extraordinary, and they had never seen anything like it before. They looked me up and down, touching my dress." The Kalmyks measured their legs with the legs of a foreigner, persuaded the traveler to bare his chest, which was examined and felt, fulfilled de Bruin's desire to look at their breasts [16, p. 229]. Taishi Daichin and Monchak showed great attention to the appearance and weapons of Celebi, marveled at the patterns of the napkin of Ismihan Kaya Sultan, daughter of the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV, and attached it to the headdress [15]. The observers' information became the source of the ideas of Europeans and Ottomans about the Kalmyks at a later time. The French spy Chevalier d'Eon replicates this image. In Siberia, he writes, they noticed a horde of Kalmyk Tatars who "see almost nothing in the light of the sun, but at night their eyesight is excellent. They are from the breed of stray bats that kill passers-by on the fly."[24] The journalist V. M. Stroev wrote in his essay "How Russia is known in Paris" in 1839: "The Frenchman thinks that we are all Cossacks. A Russian and a Cossack are exactly the same in Paris. Russian Russians think that a civil Cossack was called a Russian, and a military Russian was called a Cossack; however, in essence (au fond) it is exactly the same thing. Russian Russians, as a result of such a generally accepted opinion, are surprised not to find a Kalmyk physiognomy in Russian, that is, a flattened nose, prominent cheekbones, and says: "Monsieur n'a pas l'air russe, du tout, du tout" (You, sir, do not look at all, not at all Russian)" [Cit. according to: 25, p. 410]. In the same year, the writer and traveler A. de Custine wrote that Tsarevich Alexander "does not look at all like a Kalmyk" [25, p. 22]. The writer O. Balzac in the novel "Ursula Mirue" in 1842 describes his character Minoret-Levrault in this way: "he was so peculiar in his mediocrity. Imagine an animal to the core, and you will get Caliban, and this is not a joke. Where Form takes over, Feeling disappears. The postmaster, a living confirmation of this axiom, belonged to those beings in whom the riot of the flesh prevents even the most thoughtful observer from discerning even the slightest movement of the soul... The postmaster, who spent a lot of time in the sun, had a bluish-brown face. Deep-set gray eyes, slyly peering out from under black bushy eyebrows, resembled the eyes of the Kalmyks who came to France in 1815; if they sometimes lit up, it was only from a single thought - the thought of money" [23, p. 21]. As you can see, an ethnic stereotype is used as an image of a hostile "Other" to show the inner world of the character. †The writer A. Dumas, visiting the house of Noyon (the owner of the ulus Ц E. D.) S. Tyumen in 1858, will see signs of belonging to civilization in his life: the "European outfit" of Prince Tyumen's sister, a piano in the living room, dishes of European cuisine, the album of the princess. [24, p. 667].

Discussion and conclusion. The analyzed sources allowed us to look at the world of the authors from the inside. Travelers evaluate Kalmyks from the point of view of their own value system, giving their actions a negative meaning. The cultural baggage of travelers and the acquired picture of the world determined their perception of unusual ethnic realities. The rhetoric of otherness, starting with the definition of the Kalmyk people as barbaric, robber, unclean, has moral nuances. The ethnic stereotype contains comparison and evaluation due to differences in historical experience. By recording negative external influences (scarcity of nature, hostility of neighbors), observers create a passive image of Kalmyks. Their lifestyle, subordinated to the natural cycle, is considered as not conforming to the norms. Talking about the prospects for them, travelers pin their hopes on the beneficial effects of religion and familiarization with "their" civilization. Witsen writes that if the Kalmyks are among well-behaved people, by virtue of their understanding, they will learn any craft and the Christian religion. He met a Kalmyk woman, bought by a Dutch man who taught her religion and virtue in work. The observer believes that the Kalmyk people, if taught, are as understanding as other people, that their "wildness and stupidity" do not come from nature, but from upbringing and customs [13]. When explaining the difference between "their" and "someone else's" world, the authors used techniques of comparison and inversion, emphasizing the differences for the reader: "Among them it is considered a sin that we do not consider evil, and what we consider a serious crime is not considered a sin among them" [13, p. 413]. We have seen that the interpretation of other people's realities is achieved with the help of such topos of ethnographic discourse as fictional stories, miracles. The image of the Kalmyks is based on religious criteria. The stories of their idolatry are complemented by representations of their moral imperfection. Through the denial of negative traits attributed to "Others", there was the formation of one's own identity, a stable image of "One's Own".

References

1. Lyubimov, Yu. V. (2009). The Image of the Other (East in the European tradition). Historical psychology and sociology of history, 1, 21-47.

2. Lack, D. F. (1965-1993). Asia in the making of Europe. Vol. 1-3. Chicago.

3. Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. N.Y.: Pantheon.

4. Said, E. (2003). The East-traveler and teachings: between the dictionary definition and bright thought. Otechestvennye zapiski, 5, 466-472.

5. Neumann, I. (2004). Using the “Other”: Images of the East in the formation of European identities. Trans. from English V. B. Litvinov and I. A. Pilshchikov, preface. A. I. Miller. Moscow: New publishing house.

6. Slezkine, Y. (1994). Naturalists Versus Nations: Eighteenth-Century Russian Scholars Confront Ethnic Diversity. Representations, 47, 170-195.

7. Kon, I. S. (1999). Sociological psychology. Moscow: MPSI; Voronezh: publishing house NPO "Modek".

8. Russia and the world through each other’s eyes: from the history of mutual perception (2000-2012). Issue 1-6. Moscow: IRI RAS.

9. Vozchikov, D.V. (2020). The image of the East in medieval European culture: textbook. allowance. Ed. V.A. Kuzmina. Ekaterinburg: Ural Publishing House. Univ.

10. Repina, L.P. (2012). “National character” and “image of the other”. Dialogue with time, 39, 9-19.

11. A detailed description of the journey of the Holstein embassy to Muscovy and Persia in 1633, 1636 and 1639, compiled by the Secretary of the Embassy Adam Olearius (1870). Moscow: Society of History and Russian Antiquities at Moscow. Univ.

12. Witsen, N. (1996). Travel to Muscovy, 1664-1665. Drawings and engravings from fig. N. Witsen. St. Petersburg: Publishing house "Symposium".

13. Witsen, N. (2010). Northern and Eastern Tartaria, including areas located in the northern and eastern parts of Europe and Asia. Trans. from Dutch. V. G. Trisman. T. I-II. Amsterdam: Pegasus.

14. Streis, Ya. (1880). Three journeys. Russian archive. Book. 1. P. 5-109.

15. Celebi, E. (2008). Travel Book. Crimea and adjacent regions. (Extracts from the writings of a 17th century Turkish traveler). Ed. 2nd, corrected and supplemented. Simferopol: DOLYA publishing house.

16. Bruin, K. de (1873). Travel through Muscovy by Cornelius de Bruin. translation from French by P. P. Barsov; verified according to the Dutch original by O. M. Bodyansky. Moscow: Publication of the Imperial Society of History and Antiquities of Russia at Moscow University.

17. Bell, J. (1896). Travel through Russia to various Asian lands, namely: to Ispagan, to Beijing, to Derbent and Constantinople: Extracting their descriptions of travel. Astrakhan collection. published by the Petrovsky Observer Society of the Astrakhan Territory. Astrakhan, 1, 219-236.

18. La Relation suivante contient des Remarques singulières et assez curieuses sur les mœurs, usages, habillement, Religions, etc. de quelques peuples qui sont sous la domination de Muscovie; elle a été faite par une personne digne de foi qui a non seulement a traversé tout le pays, dont il parle, mais qui même a vécu chez quelques unes des Nations qui sont comprises dans ce mémoire particulier. Oxford, Bodieian Library, Mss, Carte papers 262, fol. l5vo.

19. Lerkh, I.Ya. (1790) Extract from the journey of John Lerch, which lasted from 1733 to 1735 from Moscow to Astrakhan, and from there to the countries lying on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. New monthly works. Part 43, 1, 3–53. Part 44, 2, 69–97. Part 45, 3, 66–100.

20. Zaitsev, I.V. (2007) About how the Turks called Russians in the 15th–20th centuries. Image of Russia and Russian culture in Turkey: history and modernity. Moscow: Institute of Oriental Studies RAS. P. 5-16.

21. Lettres, mémoires et négociations particulières du chevalier d'Éon (1764). London.

22. Custine, A. de. (1996) Russia in 1839: In 2 vols. Transl. from fr. edited by V. Milchina; comment V. Milchina and A. Ospovat. T. I. Per.V. Milchina and I. Staff. Moscow: Publishing house named after. Sabashnikov.

23. Balzac, O. (1989). Ursula Mirue. Moscow: Fiction.

24. Dumas, A. (2009). From Paris to Astrakhan. Fresh impressions from traveling to Russia. Translation from French. V.A. Ishechkina; author entry Art. and note. V.A. Ishechkin. Moscow: Sputnik+ Publishing House.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

In the second half of the XVI century, as the borders of the Moscow state expanded, its gradual transformation from a monoethnic to a multiethnic state began, in which peoples living in the vast Eurasian spaces differed in language, culture, economic structure, religious affiliation and temperament. It is the multinational composition that is an important distinctive feature of Russia, and therefore a truly scientific study of the peoples inhabiting our country is necessary. Of particular interest here is the view of foreigners on the ethnic groups of Russia. These circumstances determine the relevance of the article submitted for review, the subject of which is the image of the Kalmyks created by foreign travelers of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century. The author sets out to identify the factors that led to the perception of Kalmyks by observers, to consider the means used by foreign travelers, recreating in travelogues the main features of the image of Kalmyks, to show an assessment of the socio-cultural consequences that arose as a result of the formation of ethnic stereotypes about Kalmyks. The work is based on the principles of analysis and synthesis, reliability, objectivity, the methodological basis of the research is a systematic approach, which is based on the consideration of the object as an integral complex of interrelated elements. The scientific novelty of the article lies in the very formulation of the topic: the author seeks to characterize the image of the Kalmyks in the descriptions of foreign travelers of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century. The author shows that "travelogues of the XVII Ц first half of the XVIII century were chosen as the material for constructing the image of the Kalmyks by observers. They allow taking into account the subjective moment of perception, revealing the problem of historical reality and its representation in a historical source." Considering the bibliographic list of the article, its scale and versatility should be noted as a positive point: in total, the list of references includes over 20 different sources and studies. The undoubted advantage of the reviewed article is the involvement of foreign literature, including in English and French, which is determined by the very substitution of the topic. The source base of the article is primarily represented by the works of Adam Orealia, John Bell, Cornelius de Bruin and other foreign travelers to Russia. From the studies used, we will point to the works of Yu.V. Lyubimov and I. Neumann, who consider the image of the "Other" on the example of the East. Note that the bibliography is important both from a scientific and educational point of view: after reading the text of the article, readers can turn to other materials on its topic. In general, in our opinion, the integrated use of various sources and research contributed to the solution of the tasks facing the author. The style of writing the article can be attributed to scientific, at the same time understandable not only to specialists, but also to a wide readership, to anyone who is interested in both the image of the "Other", in general, and the image of the Kalmyk people, in particular. The appeal to the opponents is presented at the level of the collected information received by the author during the work on the topic of the article. The structure of the work is characterized by a certain logic and consistency, it is possible to distinguish the introduction, the main part and the conclusion. At the beginning, the author determines the relevance of the topic, shows that "despite the brevity of the remarks related to the lack of travel time, travelogues, fixing the picture of the "alien" world, reflect common simplified attitudes." The paper shows that "travelers evaluate Kalmyks from the point of view of their own value system, giving their actions a negative meaning." It is noteworthy that "by recording negative external influences (the scarcity of nature, the hostility of neighbors), observers create a passive image of Kalmyks." The main conclusion of the article is that "through the denial of negative traits attributed to "Others", there was the formation of one's own identity, a stable image of "One's Own". The article submitted for review is devoted to an urgent topic, is provided with a drawing, will arouse readers' interest, and its materials can be used both in lecture courses on the history of Russia and in various special courses. In general, in our opinion, the article can be recommended for publication in the journal Genesis: Historical Research.

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|