|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

Litera

Reference:

Liu J.

The subjective structure of the narrative literary text and the "I" character

// Litera.

2022. ¹ 8.

P. 33-43.

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8698.2022.8.38576 EDN: QMLKQD URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=38576

The subjective structure of the narrative literary text and the "I" character

Lyu Tszyue

PhD in Philology

Lecturer, School of Russian Studies, Xi'an International Studies University

710128, China, Shaanxi Province, Xi'an, Wenyuannanlu str., 1

|

liujue0909@mail.ru

|

|

|

|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8698.2022.8.38576

EDN: QMLKQD

Received:

06-08-2022

Published:

13-08-2022

Abstract:

This article is devoted to the analysis of the construction and composition of the subject structure of the narrative literary text. At present, the question of the interaction between the narrator and the character (author and hero), as different subjects of speech and subjects of consciousness, has been studied a lot, but the analysis of the positions of different subject components in the subject structure needs to be further developed. Based on the interpretation of the narrative structure, this article attempts to build the subject structure of the narrative literary text. Clarification of the level hierarchy of the subject structure is necessary to pin down the location of subject components and analyze the nature and types of communication between subjects. Taking the character as an example, this article describes several different situations, in which a character refers to himself in the first person as "I" within the subject structure, and also explains the differences between the narrator as a speaker and the character as a speaker. At the end of the article we conclude that the character’s "I", appearing on the plane of discourse, does not have "subjectivity" in the strict sense, but is essentially related to the narrator's strategic operations in terms of voice, consciousness and point of view. The functional sphere of the character's subjectivity is limited only on the plane of story. The voice and consciousness of the characters on the plane of discourse do not belong to the "I"-sphere, but to the "He"-sphere, as some citations by the narrator. Accordingly, the opinion that "the narrator can step in the story" is also misleading. The "character-bound narrator" has a dual identity — "character" and "narrator", and only one of them functions on the plane of story or discourse.

Keywords:

narrative fiction text, narrative structure, subject structure, narrative communication, history, discourse, narrator, character, direct speech, indirect speech

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

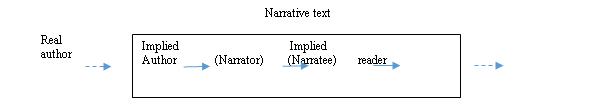

1. Narrative structure and subject structure of a narrative literary text Before describing the subject structure of a narrative literary text (hereinafter – NXT), we need to designate its subordinate concept – the narrative structure[1], which is a prerequisite for describing the first. From the point of view of structuralism, any structure is a unity consisting of several levels, each of which contains several different components, and moreover there are interactions between the levels, as well as between the various constituent components within them. Structuralist narratology believes that narrative is a kind of structure, and one of the main tasks of narrative research is to abstract general characteristics from various types of narrative works and build a basic narrative structure. To do this, it is first necessary to distinguish its various levels and various components, as M. Bal put it, as a key and effective tool, such a differentiation of layers is necessary for a detailed analysis [1]. "Composition[2] is the division and interrelation of heterogeneous elements, or otherwise, components of a literary work," however, as Kozhinov points out, the term "composition" does not have an unambiguous interpretation; composition is sometimes understood as a purely external organization of the work (division into chapters, parts, phenomena, acts, stanzas, etc. – "external composition"), sometimes it is considered as a structure of artistic content, as its internal basis ("internal composition"). Moreover, composition is often identified with other categories of literary theory – a plot, a plot, even a system of images [5]. It can be seen that the understanding of "structure", "composition" is different, and accordingly, the levels of their separation, as well as the constituent components, are different. Here we tend to interpret the narrative structure through such concepts as "plot" and "plot", and on this basis analyze its stratification. Russian formalists distinguish between "plot" and "plot", the first refers to the source material of the story, these are the events themselves; the second refers to the story told. The sequence of events reflected in the plot is artistically organized and presented in works of art. Similarly to this division, the Dutch specialist in the field of narratology M. Bal places narrative works on three levels: text, history, plot (English “text”, “story” and “fabula”)[1]. The American scientist S. Chetman divides the narrative into two aspects: history and discourse (English “story” and “discourse”). He noted that history means "what" of the narrative, that is, the content; discourse is understood as "how", which refers to the way events are transmitted, that is, to the expression [3]. M. Bal's three-point method is essentially the same as S. Chetman's dualism, although he did not use the term "text", but in his monograph "Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film" after the above content, he writes: We must distinguish between the discourse and its material manifestation – in words, drawings, or whatever. The latter is clearly the substance of narrative expression, even where the manifestation is independently a semiotic code. Generally speaking, “story” and “fabula” correspond to the content of the narrative, while “text” (according to S. Chetman's term “discourse” + “substance”) corresponds to the expression of the narrative. Thus, the narrative structure is a unity consisting of a plan of content and a plan of expression. For the convenience of unifying terminology, below we use "history" to denote the content plan of the narrative structure, and "discourse" – the plan of expression. A narrative literary text is the object of our factual analysis, that is, it is a literary work that we directly encounter as ordinary readers. Different and all kinds of narrative texts have some basic features and features in the narrative structure, but because of the different content and methods of narration, they also have different concrete implementation. Thus, the subject structureThe NXT is a subjective organization reflected in narrative works, with different subjective components from two planes – the plan of history and the plan of discourse. The literary work reflects the artistic world created by the writer. The subjective components on the plane of history are the characters living in this world. As L. A. Nozdrina writes, "in a literary text, the author, through a system of artistic images, creates a fictitious, poetic world in which either characters fictitious by the author or personalities who existed in reality, but passed through the prism of the author's fantasy, acting in some fictional situations, act" [7]. Unlike real communicative behavior, speech communication on the NXT discourse plane is not built between individual real speakers and listeners, but on the basis of a very complex communicative situation: the subjects on the discourse plane are the author, the implicit author (English “implied author”), the narrator (narrator or narrator, English “narrator”), the narrator (English “narratee"), implicit reader (English “implied reader") and reader. This complex narrative communication can be represented through the scheme of the "narrative-communicative situation" by S. Chetman [3].

According to S. Chetman, a narrative is a kind of communication, therefore it assumes two actors – the sender and the recipient. Each side contains three different roles. The sender includes a real author, an implicit author and a narrator, and the recipient is a real reader, an implicit reader and a narrator. E. G. Samarskaya believes that there are four types of dialogue in literary texts: first, a dialogue between the writer and the audience to which he addresses and to whom he addresses his work. Secondly, it is a dialogue of those personalities who are represented in the text itself, that is, the heroes of the work itself. Thirdly, it is a dialogue between the author and his characters. And finally, it is a dialogue between the characters of the text and the readership. Each dialogue does not exist by itself, but is part of a whole complex of relations on which the communicative chain "author (writer) – text (artwork) – recipient (readership)" is based [9]. 2. Hierarchy of the subject structure of the NXT The components in the subject structure are not only divided into two aspects – the subject on the plane of history and the subject on the plane of discourse, but there are also hierarchical differences between these components, and from this point of view, the four types of dialogue between different subjects listed above, put forward by E. G. Samarskaya, are also not on the same level. The model of the narrative-communicative situation constructed by S. Chetman contains a basic-level division: an implicit author and an implicit reader are inherent in the narrative, and the narrator and narrator are optional (in parentheses). A real writer and a real reader are themselves outside of narrative communication [3]. Based on the above, we take "history – discourse – text" as a boundary and separate several communication chains depending on the location of the subject components. 1) external text level author—text (artwork)— reader Communication between a real author and a real reader is external to the text. Such communication about the work takes place in an indirect way, and, of course, in some cases there are personal verbal exchanges, even direct face-to-face communication. 2) the in-text level a. implicit author—history—implicit reader "Only the implicit author and the implicit reader are immanent in the narrative" [3]. Despite the fact that in his presentation O. A. Melnichuk does not use the terms "implicit author" and "implicit reader", he obviously means the relationship between these two concepts: "a work of fiction is a meeting place between the author and the reader, where the author communicates to the reader his innermost thoughts. The writer strives to ensure that the reader accepts the work, then a conversation will start between him and the author. While working on a work, a dialogue takes place between the author and his exemplary reader, i.e. the writer builds his own reader model throughout the text" [6]. The concept of "implicit author" was proposed by W. Booth [2], and it caused and still causes heated debate today, but there is a unanimous opinion that the implicit author is different from the real author, from the writer, he is closely connected with the creation of the work and cannot be separated from the work itself. There may be different implicit authors in different works of the same author. b. narrator—story—narrator At the intra-textual level, there is another communication chain that is established between the narrator and the narrator. The narrator is the one who tells the story, and the addressee, the audience of his narration is the narrator. The narrator differs from the implicit author, especially when their concepts and positions are incompatible. 3) the level between history and discourse Communication between the narrator and the character has a great feature, since they are on different levels: the narrator is on the plane of discourse, and the character is on the plane of history. There is no direct verbal communication between the narrator and the character inside the story, such communication can only be established between the characters. The character-narrator (“character-bound narrator" according to the term M. Bal), apparently, can conduct a dialogue with some character, but it should be noted that the dialogue with the latter is conducted by the character-narrator not in the hypostasis of the narrator, but in another hypostasis - the character in this story. Outside of history, on the plane of discourse, there is also no direct verbal communication between the narrator and the character, because the boundary between history and discourse separates them, and each of them has its own space-time positioning. The "communication" between the narrator and the character is an inter–level communication that covers two planes of history and discourse. The voices of the characters appearing on the plane of discourse are ultimately quotations of the narrator. As a Chinese scholar in the field of narratology, Shen Dan noted that, unlike films and dramas, "in novels, the words of characters must be conveyed to readers by a narrator who is in a different time and space" [11].

4) the level inside the story Within the story, communication between subjects is established between different characters, and such communication is very similar to our everyday speech communication, if we do not take into account the factors of the author's design. In addition to the dialogue between the characters, there may be a monologue of the character in the text. Thus, we can depict the following scheme of the subject structure of the NXT, which shows the stratification of this structure and the location of each subject component, as well as the communicative situation between the subjects. The above-mentioned narrative-communicative situation of S. Chetman was created only at the level of discourse, therefore the character, as a subject on the plane of history, is not included. In the subject structure of the NXT that we have constructed, we are talking here not only about the narrative act, and it concerns not only the plan of discourse, so the character is obviously an important, irreplaceable component, especially since the character can sometimes also play a narrative role. As V. Schmid's model of communicative levels is shown, an optional third level is added to the author's and narrative communications, "if the narrated characters, in turn, act as narrating instances" [10]. The subject structure of the NXT is a complex organization, and its complexity is manifested not only in the fact that the structure contains many subject components, but also in the multilayered structure and multiple identity of the subject. The multiplicity of subject identity is perceived from two sides: firstly, each type of subject component can be accepted by several individuals, narrative works can be written by several authors or narrated by several narrators, and there are several characters in the story; secondly, the identity of the subject is transformable: the character can also tell a story, at this time the character's personality is transformed into a narrator of a secondary discursive-historical structure. In the study of narrative semantics, E. V. Paducheva examined in detail the issues of the "speaker" of the narrative text, from her presentation we will see the complexity and specificity of the speaker's role in the narrative [8]: On the other hand, a literary text is a speech work, and as such it is characterized primarily by its subject of speech. In colloquial language, it is the speaker. It would seem that in a narrative text it should be the author-creator of the text. However, the situation is more complicated, and there is no direct correspondence between the speaker in the spoken language and the author-creator of the literary text. When we set the task of describing the semantics and functioning of language in a literary work, we can only talk about the analogues of the speaker. The speaker in the narrative text differs from the speaker of ordinary colloquial speech, it is "an analogue of the speaker," according to E. V. Paduchev, "not the author himself, ... and the image of the author, more precisely, the narrator," in a free indirect discourse, is a character [8]. From here it can be seen that the role of the speaker in the NXT is stratified. The author, narrator and character, as independent personalities, perform speech functions in their own way. 3. The character "I" in the NXT Below, combining the relevant coverage of scientists and the divided plans of "history – discourse – text", we will outline the subject-character, describe in more detail those cases when the character calls himself "I" in the NXT. The character appears in the text in the first person "I" usually in the following situations: 1) A character on the story plan. The character uses "I" in dialogue with other characters or in a monologue. The dialogue of the characters is expressed by the narrator in the form of direct speech. — Remember, Anna: what you have done for me, I will never I'll forget. And remember that I I love and will always love you as my best friend!

— I don't understand why," she said.Anna, kissing her and hiding her tears. — You understand me and you understand. Goodbye, my darling! (L. Tolstoy. Anna Karenina) 2) "I" as a narrator character. In this case, "I" is used to denote a dual personality – a narrator and a character. At these words, a girl of about fourteen years old came out from behind the partition and ran into the hall. Her beauty struck me. "Is this your daughter?" I asked the caretaker. (Pushkin. Stationmaster) The form of the first person "I" here refers to both the narrator and the main character of the story. But it is still possible to distinguish that the main content of this fragment is told in the form of the narrator's memories, therefore it is the narrator's speech (the narrator as a speaker on the plane of discourse), and only direct speech ("Is this your daughter?") is the speech of the character (the character as speaking on the plane of the story). 3) Starting to tell a story, the character acts as the "I"-the narrator of the secondary discursive-historical structure. In relation to the big story of the whole text, this "I" is the narrator of a small story. It should be noted that in the secondary discursive-historical structure, an "external narrator" is also distinguished (English "external narrator", in the case of a narrative about someone else's story, or according to the interpretation of M. Bal [1], "this term indicates that the narrator does not appear in the plot as an actor") and "character-narrator" (when telling about his story, or the narrator himself is one of the characters in his story). — Here (he filled his pipe, took a drag and began to tell), you see, I was then standing in the fortress behind the Terek with a company — this will soon be five years old. (Lermontov. The hero of our time) In the novel "The Hero of Our Time", the story of the heroine Bela is told by the character Maxim Maksimych. From the above text fragment it can be seen that the phrases in parentheses(he filled his pipe, took a drag and began to tell) – this is the speech of the narrator of the whole work (i.e. the character is a narrator of the primary rank), in relation to him, the hero Maxim Maksimych is a third person, therefore the third person pronoun "he stuffed" is used. The rest of the words in this fragment belong to Maxim Maksimych, who began his story about Bel and Pechorin, so that he became a character narrator of secondary rank, using the first-person pronoun "I then stood..." to denote myself. 4) The character "I" in free direct speech. The narrator in his narration directly introduces the character's speech, and this is in such cases when the form of the face "I" is preserved in direct speech from the point of view of the character, and the words of the author (narrator) are absent.

His mother's letter had exhausted him.But as for the most important, capital point, there was no doubt in him for a minute, even while he was still reading the letter.The main point of the matter was decided in his head and finally decided: "This marriage will not happen while I am alive, and to hell with Mr. Luzhin!"?Dostoevsky. Crime and punishment) This is a fragment from "Crime and Punishment". The underlined part is a monologue of the main character Raskolnikov. Here, the narrator of the novel uses free direct speech to directly represent the inner thoughts of the character, and the personal form of the character "I" is preserved in the quote. Consequently, from the above analysis it can be seen that in direct speech (including free direct speech) expressing the speech of the character, the role of the speaker is played by the character, and with the exception of this case, the narrator himself assumes the role of the speaker. Although there are elements in indirect speech that reflect the consciousness and speech of the character, first-person forms (personal pronouns, possessive pronouns or first-person verb forms) are not possible in it, since in indirect speech they need to be transformed into third-person persons. In general, it is advisable to generalize the role of the speaker in the NHT with the words of M. Bal: "More precisely, the writer pulls away and calls for a fictitious representative, a narrator. But the narrator does not tell continuously. Whenever direct speech occurs in the text, the narrator temporarily gives this function to one of the actors. When describing text layers, the key question is who is leading the narrative"[1]. However, as mentioned above, the narrator and the character are at different levels, and they are completely unequal in the performance of the role of the speaker. In this regard, M. Bal in the narrative hierarchy divides the narrator as a speaker of primary rank and the character as a speaker of secondary rank. S. Chetman also emphasizes that the narrator and the character are at different levels, and the spheres and functions of their speech acts are also different, "even when a character tells a story within the framework of the main story, his speech acts always inhabit the plane of history, not the plane of discourse," the character can only interact directly with other characters, and their speech acts, such as apologies and warnings, can only be addressed to other characters. The central speech act of the narrator is precisely narration. The narrator in some works can also perform such speech acts as an apology and a warning, but this is only for the narrator, he "can only apologize or warn for the narrative itself" [3]. Conclusion Clarification of the construction and level hierarchy of the subject structure is necessary for the orientation of the subject components and the scope of their functional activity within the framework of the NXT, and is also important for the cognition and clarification of some basic concepts in the research of narratology. The division "history/discourse" (French "histoire/discours") was first put forward by the French linguist E. Benveniste. Then, having received great development in the field of narratology, they became the two main concepts for describing narrative works. If the narrator and the character act as separate independent individuals, then their "subjectivity" is formed and manifested precisely in their speech activity – thanks to language, more precisely, through the use of language, "a person is constituted as a subject" according to E. Benveniste[4]. Thus, the narrative "I" through its narrative behavior is realized on the plane of discourse, while the character, as an actor and a real speaker in the story, its "subjectivity" is established only on the plane of history. In the thesis "Man in Language", E. Benveniste emphasized the opposition of "I" and "not-I", based on this, it can be determined that on the one hand, some elements that appear on the plane of discourse and reflect the subject of the character are essentially the results of a strategic operation of the narrator's narrative: either the acceptance of the character's point of view, or borrowing his words and consciousness, so that on the plane of discourse, the "I"-the sphere of the narrator and the "not-I"-the sphere ("He"-the sphere) of the character are distinguished; On the other hand, as for the term "character-narrator", in relation to the narrative "I" as a subject the character "I" on the plane of history is essentially the object of the narrative, and the very form of "I" in the text indicates only the referential correlation of the designated object with the subject of the speech act.

[1] We say that the narrative structure is a higher concept of the subject structure, because the components of the subject structure are only part of the narrative structure. The components of the NS story plan include: "event", "character", "time" and "place", the narrator (narrator or narrator), the time and rhythm of the narrative, etc. The narrative discourse can be narrative or non–narrative, as a comment or description. [2] Instead of the term "structure", "composition", words similar in meaning are used: architectonics, construction (or structure), construction, etc. (see Kozhinov V. V. Composition // KLE. – Vol. 3.)

References

1. Bal M. Narratology: introduction to the theory of narrative (4th.e.). University of Toronto Press, 2017.

2. Booth W. C. The rhetoric of fiction. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1961.

3. Chatman S. Story and discourse: narrative structure in fiction and film. Ithaca and London: Cornel University Press, 1978.

4. Benveniste E. General linguistics. URSS, 2002.

5. Concise literary encyclopedia (CLE). vol. 3. Ì., 1966.

6. Melnichuk Î. À. The first-person narration. Interpretation of the text (on the material of modern French-language literature): Ph. D. dissertation. Moscow State University. Ì., 2002.

7. Nozdrina L. À. Interpretation of a literary text. Poetics of grammatical categories: a textbook for linguistic universities and faculties. Ì., Drîfà, 2009.

8. Paducheva E. V. Semantic research: Semantics of time and aspect in Russian; Semantics of Narrative (2nd.e.). Ì., Languages of Slavic culture, 2010.

9. Samarskaya E. G. Autobiographical presentation as a representative of the personality of a character in a literary text: dissertation of the candidate of philological sciences. Krasnodar, 2008.

10. Schmid W. Narratology. Ì., Languages of Slavic culture, 2003.

11. Shen D. Studies in narratology and stylistics of novels (4th.e.). Beijing, Peking University Press, 2019.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

Conceptually verified works on literary theory have been quite rare lately. Probably, the necessary data cross-section and generalization of subject-specific sources are missing. It is worth noting at the beginning that the reviewed article does not pretend to be some kind of heuristic study, however, most of the positions attract attention, especially since the necessary objectification of the issue is done professionally / competently. The content level of the work is high, the proper argumentation of the view is presented accurately. For example, this can be seen in the following fragments: "from the point of view of structuralism, any structure is a unity consisting of several levels, each of which contains several more different components, and moreover there are interactions between the levels, as well as between the various constituent components within them", or "generally speaking, "story" and “fabula" corresponds to the content of the narrative, while “text" (according to S. Chetman's term “discourse" + “substance") corresponds to the expression of the narrative. Thus, the narrative structure is a unity consisting of a plan of content and a plan of expression. For the convenience of unifying terminology, below we use "history" to denote the plan of content of the narrative structure, and "discourse" – the plan of expression. A narrative literary text is the object of our factual analysis, that is, it is a literary work that we directly encounter as ordinary readers. Different and all kinds of narrative texts have some basic features and features in the narrative structure, but due to the different content and methods of narration, they also have different concrete implementation," or "unlike real communicative behavior, speech communication in terms of NHT discourse is not built between individual real speakers and listeners, but on the basis of very a complex communicative situation: the subjects in terms of discourse are the author, the implicit author (English "implied author"), the narrator (narrator or narrator, English "narrator"), the narrator (English "narratee"), the implicit reader (English "implied reader") and the reader,"etc. The analysis of this problem is supplemented by the author pictograms, diagrams, drawings. It seems that such a technique can be regarded as an active, systemic one. Links and quotations are given in the mode of productive dialogue with opponents. I believe that the author uses terms and concepts in the right contextual way, there are no actual discrepancies, and the work often provides a comment that is necessary for an interested reader. The text of the article is differentiated into so-called semantic blocks, the logical connection is supported by the internal regulation of the researcher's appeal to one or another alternative point of view. The methodology of the article does not contradict the existing base of developments: the principle of "hierarchy", the variant of "subject organization of the text", "component analysis", the opposition "author – text – reader" are given / presented correctly. The style of the work correlates with the scientific type itself: for example, "communication between a real author and a real reader is external to the text. Such communication about the work takes place in an indirect way, and, of course, in some cases there are personal verbal exchanges, even direct face-to-face communication," or "at the intra-textual level, there is another communication chain that is established between the narrator and the narrator. The narrator is the one who tells the story, and the addressee, the audience of his narration is the narrator. The narrator differs from the implicit author, especially when their concepts and positions are incompatible," or "the subject structure of the NXT is a complex organization, and its complexity is manifested not only in the fact that the structure contains many subjective components, but also in the multilayered structure and multiple identity of the subject," etc. The purpose of the work has been achieved, a number of tasks have been solved as a whole, the topic has been fully disclosed. In my opinion, it would be possible to complicate/ expand the block of examples, although there are enough references to the texts of A.S. Pushkin, M.Y. Lermontov, F.M. Dostoevsky, L.N. Tolstoy. The basic requirements of the publication are taken into account, although when making footnotes it is advisable to use the option "..." [2, p. 22], indicate the full volume of pages in the list of sources. In the final, the author notes that "clarification of the construction and level hierarchy of the subject structure is necessary to orient the subject components and the scope of their functional activity within the framework of the NXT, and is also important for cognition and clarification of some basic concepts in the research of narratology." Thus, the research in the chosen direction should be continued, and this pleases, allows you to move along the already planned highway. I recommend the article "The subject structure of a narrative literary text and the character self" for publication in the journal "Litera".

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|