|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

Man and Culture

Reference:

Astashev D.A.

Ornamentation in the musical-theoretical teaching of Giusto Dacci: a didactic standard

// Man and Culture.

2024. ¹ 1.

P. 81-91.

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8744.2024.1.68784 EDN: XBIGNE URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=68784

Ornamentation in the musical-theoretical teaching of Giusto Dacci: a didactic standard

Astashev Dmitry Anatol'evich

ORCID: 0000-0002-6910-9675

PhD in Pedagogy

Professor, Musical Art Department, Arctic State Institute of Culture and Art

677000, Russia, Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), Yakutsk, Ordzhonikidze str., 4

|

astashev_dmitry@mail.ru

|

|

|

|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8744.2024.1.68784

EDN: XBIGNE

Received:

23-10-2023

Published:

05-03-2024

Abstract:

The article draws attention to the system of musical ornaments given in the didactic standard of the Italian teacher of the mid-XIX century Giusto Dacci. Created in the conditions of the changed practice of performance, where the importance of reading the musical text as close as possible to the composer's intentions, Maestro Dacci's ornamentation system not only offered teachers their unification in the form of abbreviated letter signs, but also set standards for their decoding. In relation to the content of the music theory, section related to the study of ornamentation, the Dacci system has become the organizing construct that has acquired a stable form of didactic generalization. The types of ornamentation highlighted by Giusto Dacci: appoggiatura – accaccatura – mordent – gruppetto – trill, these are the elements of musical theory that retain universality to this day. They were introduced into the didactic standard at a special historical moment of the active creation of methodological concepts that provide theoretical and technological foundations for pedagogical work in professional musical educational institutions in Italy. Such work not only enriched the musical culture of the XIX century. In the formation of basic coloring skills, it remains an important educational guideline today. 1. In music theory, it captures the experience of accurately encoding ornaments. This experience, in fact, is the key to the visualization of an unchanging sound. For musicology, it is of interest from the point of view of studying the history of the formation of the cycle of musical-theoretical disciplines and its content. 2. In educational practice, it expands the existing format of knowledge, opens up the opportunity for teachers to include this educational material in their practical work. 3. In performance, it allows to understand the facets of possible performing freedom in deciphering jewelry in works taken from a particular time chronotope.

Keywords:

decorations in music, music theory, Giusto Dacci, the doctrine of ornamentation, didactic standard, terminology, appoggiatura and accaccatura, mordent, gruppetto, trill

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

In the history of Italian musical science and professional pedagogy, decorations (it. abbellimenti), originating from the medieval experience of sacred glorification, have been a constant topic of discussion in numerous theoretical and practical teachings[1]. However, initially they had terms different from abbellimenti. For example, in book III of the Etymologies of the medieval encyclopedist Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636), to characterize the mobile decorated voice, the author used the Latin term "vinnola", meaning "soft and sinuous/flowing voice" (vinnola est vox mollis atque flexibilis)[2]. The etymology of this term was derived by the teacher of the Church from the Latin vinno, - as he himself writes, - a synonym for cincinno, indicating a curly, curly and curvy voice[3]. Since the time of Isidore of Seville, the terminological apparatus of the very concept of "jewelry" has expanded significantly. In the semantic field of the modern Italian term abbellimenti[4], except for Latin coloring (from Latin. colorare – to color), ornamentation (from Latin. ornare – to decorate, decorate), fioritura (from it. fiorire - to brighten), figuration[5] (from it. figurare - to decorate, to brighten), which are actively used today to express the necessary meaning, combining various linguistic forms in the concept of "decoration" according to the sum of similarities. But no matter how decorations are called in our time, which have absorbed different linguistic forms in the combined history of European artistic practices of the eras following the Middle Ages (cantus fractus, cantus floridus, diminutio/ deminutio, passaggi, gorgia, cantus supra librum), it is important that the meaningful and practical content of these terms has always been linked to grinding and decoration non-structural elements of the melody's baseline, both vocal and instrumental. It is in this understanding that abbellimenti considers the theoretical and practical treatise by the Italian teacher (Trattato teorico-pratico di lettura e divisione musicale) Giusto Dacci (Giusto Dacci; Parma, September 1, 1840 - Parma, April 5, 1915), published in Milan in 1867[6]. Chapter IX of this work says: "Ornaments (abbellimenti) are ornaments in music, and there are five of them: Appoggiatura –Accaccatura – Mordent – Gruppetto – Trill (Appoggiatura–Acciaccatura–Mordente–Gruppetto–and Trille); they are indicated by signs located above or below the note-bearer or small notes located between [basic /basic - my insert, D.A] notes" [1, p. 66][7]. Dacci's theoretical understanding and orderly description of jewelry in music, which tends to a universal didactic interpretation, can hardly be overestimated. After the guidance of the Italian falcetist and composer Giovanni Luca Conforto (c. 1560-1608), "A quick and easy way to teach every student to color notes ..." ("Breve et facile maniera d'essercitarsi ad ogni scolaro ..."), which appeared in 1593 and also set out to create a universal textbook for voices and instruments, specifically revealing the practice of the Italian art of diminution[8], this work became the next in the history of didactic systematization and educational practice of coloring. The fundamental difference between these two works, separated in time by more than two and a half centuries, is that each of the authors belonged to different artistic eras and, accordingly, described the practice of decoration based on the ideas of his time. In the first case, the decorations were conceptualized within the framework of free improvisation. Her examples were described in detail by Giovanni Conforto in the form of passages, trills and decoration techniques in cadences. All these examples, according to the author, could help students achieve the ability to perform improvisation beyond the baseline of any melody, and accordingly, served only as a starting point for spontaneous performance creativity. In the second case, in the practice of performance that has changed significantly since the beginning of the XIX century, in which the reading of the musical text as close as possible to the composer's intentions has become important, decorations began to gain unification in the form of abbreviated characters and the establishment of standards for their decoding. In the new conditions of a radical change in the artistic paradigm, gradually leaving the old norms of academic music for Europe (for example, in the vocal performance of the forgetful installation of opera-seria and the art of falsetists/castrati), as well as a radical change in the system of Italian musical education[9], aimed at developing theoretical and practical recommendations for actively opening up in In the 19th century, state conservatories, decorations, as an obligatory section of theory, acquired a stable form of didactic generalization. The former freedom of performance was a thing of the past. It was replaced by codified standards that capture accurate ideas about the sound implementation of decoration and are a visual analogue of sound. In the prevailing realities of the XIX century, the work of the Italian Giusto Dacci became the necessary theoretical and practical manual, which, in creating educational stamps and stereotypical templates for designating and deciphering jewelry, claimed the status of a reference didactic standard that performs the function of an indicative basis for actions of a high level of generalization. Striving, like the previous work, for universality, Maestro Dacci's treatise formulated a systematic knowledge of the types of jewelry, which in the new era, as well as Conforto's, was supposed to help musicians (both vocalists and instrumentalists) to find a good and elegant manner of their performance. Written later, at the very beginning of the twentieth century, special scientific studies on ornamentation by Adolf Beischlag[10], Hugo Goldschmidt[11], Max Kuhn[12], Heinrich Schenker[13], and then, in the second half of the same century, the work of Hans-Peter Schmitz[14] revealed in detail a very diverse the European practice of instrumental and vocal performance of jewelry in the historical perspective of the XVI-XIX centuries. However, having immersed themselves in the subtle specifics of the performing practices of individual eras and national schools, they could not contribute to the level of didactic abstraction and generalization inherent in educational material set by Giusto Dacci. So, the didactic basic standards formulated by Giovanni Luca Conforto and Giusto Dacci not only did not become a structural theoretical basis for a systematic description of the numerous variants of reading jewelry included in the historical context, but also did not find their reflection in these works. In fairness, we point out that the theoretical standard of jewelry created by Giusto Dacci in the middle of the XIX century became one of those that was actively implemented in the educational programs of Italian schools and conservatories not only during its creation. Tested by many years of application experience, this standard, being the initial basis for understanding the methodology of teaching the art of beautiful and orderly ornamentation, is well known today. The standard, performing an organizing function in relation to the content of the five types of jewelry named by the maestro, identifies a core in each of them, the knowledge of which forms the basis for universal educational actions. Solving pedagogical tasks, the standard provides the necessary set of rules describing the norms for designating ornaments in a musical text, as well as examples of their possible interpretation.

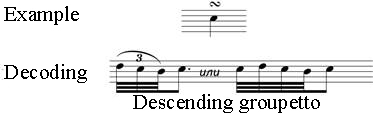

About the didactic activity of Maestro Dacci in the modern Italian encyclopedia of Trekkani, you can read: "[Dacci] was significant in the evolution of musical education; D.[acci] devoted his entire existence to him, demonstrating the special seriousness of intentions revealed by numerous published works, as well as his long and constant activity as a teacher; all works testify to his commitment to to create a very organic and coordinated curriculum that could be extended not only to the conservatory of your city, but also to all Italian musical institutions"[15]. Indeed, the didactic works of Giusto Dacci, including "Musical Grammar" (Grammatica musicale), "Theoretical and practical treatise on reading notes and sections of music" (Trattato teorico-pratico di lettura e divisione musicale), Theoretical and practical treatise on harmony" (Trattato teorico-pratico di armonia), universal programs for teaching in schools and conservatories, they made a significant contribution to the formation of the national Italian music education system, to the creation of a well-coordinated structured scheme of theoretical information that develops professional literacy. Such activities of the maestro were greatly facilitated by the socio-economic and political conditions in Italy, which laid the foundation for fundamental changes in the educational system of the second half of the XIX century. A comparison of the didactic standard of Dacci jewelry with the content of the "Melisms" section in Russian textbooks on elementary music theory, also aimed at practical training of professional musicians, shows that in our textbooks the content side of the educational material is given as truncated as possible. And if, for example, in pre-revolutionary publications, which do not always distinguish the same five types of jewelry called Dacci, but have close interpretations of the transcriptions of their individual types[16] and the abbreviated characters used, one can note typological similarity with the Italian standard, then in textbooks used in the modern educational space[17], neither the pre-revolutionary domestic, and even more so, the Italian standard is not a guideline. While agreeing that in the long history of jewelry, many of them could have gone out of use in one particular historical period, I still want to note that the types of ornaments highlighted by Giusto Dacci, and its varieties with detailed transcriptions, are those elements of music theory that remain universal to this day. They were introduced into the didactic standard at a special historical moment of the active creation of methodological concepts that provide theoretical and technological foundations for pedagogical work in professional musical educational institutions. Such work not only enriched the musical culture of the XIX century. It remains an important guideline in the formation of basic coloring skills today. And these skills are certainly important in modern performance practice. Of the five types of jewelry named by Maestro Dacci, we will pay special attention to Gruppetto, as it is insufficiently represented in the textbooks used in Russia today. A comparative analysis of the educational materials of these manuals, which are still being republished by the Lan publishing house, allows us to state: the definition of this type of decoration, the types of its designation, examples and decoding conditions do not always coincide with the Dacci theory. Meanwhile, for performers who include in their programs, including the Italian repertoire, knowledge of Italian standards for deciphering jewelry is very important, as it provides the possibility of correlation of the performing interpretation with the national practice of deciphering the Italian original. Let's pay attention: according to Dacci, a "gruppetto" is a figure of three or four[18] small/small notes that precede the (main) note, and follow one another in an ascending or descending movement. In the first case, the group is up, and in the second down. The grouppetto of three small notes should be performed quickly, and of four — in accordance with the tempo" [1, p. 68]. Example 1.

Dacci notes: "for the abbreviated designation of the groupetto, the letter esse is used , located horizontally, if the groupetto is performed in a downward movement [Example 2], and the letter esse , located horizontally, if the groupetto is performed in a downward movement [Example 2], and the letter esse  is vertical if the groupetto is performed upwards [Example 3]: it is important that if the groupetto is indicated by the sign of an abbreviated letter, its usual form consists of four small notes" [1, p. 68]. is vertical if the groupetto is performed upwards [Example 3]: it is important that if the groupetto is indicated by the sign of an abbreviated letter, its usual form consists of four small notes" [1, p. 68]. Example 2.

Example 3.

In addition, the grouppetto can be with alterations located above or below the essay icon [1, p. 68]. Example 4.

The grouppetto consists of three notes when it is placed above the main note and four when the essay sign stands after the main note [1, p. 68].

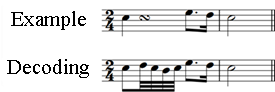

"When encountering the gruppetto sign after the note, which falls on the last eighth part of the half with a dot and a quarter figure, the gruppetto should be performed by the value of the last eighth, so that the four notes forming the gruppetto will be thirty-second, but this is with slow movement of the lento" [1, p. 69]. Example 5.

"If the tempo is fast, the grouppetto will be performed on the last fourth lobe of the figure after the half with a dot, and the four notes forming the grouppetto will be the four sixteenth" [1, p.69]. Example 6.

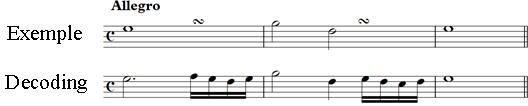

Maestro Dacci also gives examples of transcriptions of grouppetto after figures with a point of different duration [1, p.70]: Example 7.

Example 8.

He does not ignore the cases when the gruppetto is performed after the eighth on the second sixteenth and consists of sixty-four durations, as well as cases of the performance of a gruppetto located between notes with the same name. All his explanations are structured and fully comply with the requirements for the training material in terms of accessibility and clarity of presentation. It is quite obvious that for the history of the formation of the cycle of musical theoretical disciplines with their substantial content, the theoretical and practical teaching of Giusto Dacci is of unconditional interest. However, it is of no less interest to performers. After all, the knowledge about the didactic standard of the Italian teacher, introduced for the first time into the everyday life of Russian musical science, not only actualizes his theory, but also introduces the practice of encoding and deciphering abbreviated letters. And this knowledge is necessary for the performer while working on the Italian repertoire of the XIX century. The study by Adolf Beishlag [8], translated into Russian, presents an extensive history of jewelry, which on the one hand reveals their life in time, in the traditions of European national schools, in the methodological works of individual performers. On the other hand, devoid of didactic generalization, it paints a very confusing picture, which still had to pave the way to the standards of the XIX century, which appeared in the context of the formation of national musical education systems. Well aware that the development of a standard that takes into account the current state of writing, the formed type of musical thinking, became possible only in the specific historical conditions of writing practice, in which the encoded decoration was comprehended by a complete sound analogue of the sounding one, it should be remembered that this standard is hardly valid for the performance of music of the XVII - XVIII centuries. After all, the ornamentation of these times, emancipated in many ways from written norms, could still preserve the living presence of performing freedom in the variant reading preserved in the oral traditions of performing schools. It is also not valid for modern times, where sound reality "can be created through sensory experience and intellectual knowledge by "remembering" and improvising with various previously disordered constructs" [10, p. 43]. And yet, knowledge of the Giusto Dacci standard, updated in Russian music theory, is necessary for at least three reasons: 1. In music theory, it captures the experience of accurately encoding jewelry. This experience, in fact, is the key to visualizing an unchanging sound or an analog of a sounding one. For musicology, it is of interest from the point of view of studying the history of the formation of the cycle of musical theoretical disciplines and its content. 2. In educational practice, it expands the existing format of knowledge, and also opens up the opportunity for teachers to include this educational material in their practical work. 3. In performance, it is necessary to understand the facets of possible performing freedom in deciphering jewelry in works taken from a particular time chronotope. [1] See about this: Astashev D. A. Vocalizations of M. Bordogni in the value system of the Bel Canto concept// South Russian Musical Almanac. 2020. No. 3, footnote 1, p. 77. [2] Isidori. Etymologiarum Lib. III. XX. P. 152

https://archive.org/details/isidori01isiduoft/page/n151/mode/2up [3] in the same place [4] in modern Italian practice, the synonym abbellimenti - aggraziature is also used (see the article Abbellimento in the Italian Encyclopedia of Trekkani: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/abbellimento_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29 / ) [5] related, among other things, to the Baroque polyphonic practices of canto figurato, which develop the initial melodic thought [6] Dacci G. Trattato teorico pratico. Lettura e Divisione Musicale. G. Ricordi & C – Milano n. 104785 [7] Gli Abbellimenti sono ornamenti della musica, e sono cinque: Appoggiatura –Acciaccatura– Mordente –Gruppetto – e Trille, i quali vengoro indicate con segni posti sopra o sotto al rigo, o con notine collocate fra note. [8]Diminution (from Latin. deminutio – reduction, grinding) in ancient music, the form of ornaments, compositional technique, changing the beaker. Such changes were often not recorded in the written text, but were always improvised by the performer. [9] It is known that after the Great French Revolution, which marked an intellectual movement aimed at including music teaching in the state educational system, in republican Italy (under Napoleon) there was a "desire to include music teaching in the state educational system. Paris encouraged the creation of musical institutions and an important Italian motivation was socio-political renewal, taking into account the needs of the less affluent classes. The newly founded conservatories (as well as those created later in the same century), first of all, had to meet two requirements: caring for the poor and professional training of opera singers"[2, 107]. By ensuring the accessibility and mass character of music education, state conservatories were developed in Italy even after the French left the peninsula. [10] Beyschlag Adolf. Die Ornamentik der Musik. Breitkopf & H?rtel, 1908. – SS.285. [11] Goldschmidt Hugo. Die Lehre von der vokalen Ornamentik. Charlottenburg, 1907. - SS.228. [12] Kuhn Max. Verzierungs-Kunst in der Gesangs-Musik des 16. bis 17. Jahrhunderts. Leipzig 1902. SS.170 [13] Schenker Heinrich. Ein Beitrag zur Ornamentik. Beitrag zur Ornamentik. Wien. Universal Editions,1908. SS.72. [14] Schmitz Hans-Peter. Die Kunst der Verzierung im 18 Jahrhundert : Instrumentale und vokale. B?renreiter, 1955. - SS.146 [15] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giusto-dacci_(Dizionario-Biografico) [16] See: Konius G.E. [3, pp.86-88]. Section VIII "Melisms" focuses on four types of melisms without mordent (No. 821-854); Puzyrevsky A.I. [4, pp.101-104]. In Chapter VII, "Melisms", only four types of melisms are distinguished (without mordent): forschlag/appoggiatura combined with acciaccatura, having varieties: long and short; double and triple; groupetto (taking into account the positions of the sign above the note or between the notes and the corresponding transcriptions, including with chromatic reading options) and trill [17] See: I.V. Mododin [5, pp.190-195], who cites: short and long forschlags; mordent (simple and crossed out); gruppetto (taking into account the positions of the sign above the note or between the notes, but without the vertical sign and variants with chromatics); trill and arpeggiato (the latter missing from Dacci). Rusyaeva I.A. [6, pp. 82-85] in chapter VIII of "Melisms" calls forschlag (long, short), mordent (simple, double, with chromaticism), gruppetto, taking into account the positions of the sign above the note or between the notes, but without a vertical sign and variants with chromatics), trill. [18] In the domestic textbooks of B.K. Alekseev, A.N. Myasoedov [7, p. 170], I.V. Mododin [5, p. 192], I.A. Rusyaeva [9, p. 55] it is said about two types of groupetto: four-sound and five-sound. There is no question of three-sound. Curiously, none of these textbooks mention the vertical form of the abbreviated gruppetto sign and its decoding.

References

1. Dacci, G. (1847). Trattato teorico pratico. Lettura e Divisione Musicale. [Practical theoretical treatise. Reading and Musical Division]. Milano: G. Ricordi & C.

2. Daolmi, D. (2005). Uncovering the origins of the Milan Conservatory: the French model as a pretext and the fortunes of Italian opera. Musical Education in Europe (1770-1914). Michael Fend, Michel Noiray. Berlin: Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag.

3. Konyus, G. E. (1905). Collection of tasks, exercises and questions (1001) for the practical study of elementary music theory. St. Petersburg: Central State Public Library named after. V.V. Mayakovsky.

4. Puzyrevsky, A.I. (2020). Textbook of elementary music theory. 6th ed., erased. St. Petersburg: Lan: Planet of Music.

5. Sposobin, I.V. (2023). Elementary theory of music: textbook; scientifically edited by E.M. Dvoskina. – 10th ed., rev. and additional. St. Petersburg: Lan: Planet of Music.

6. Rusyaeva, I. A. (2023). Handbook of elementary music theory. Tutorial. 3rd ed. St. Petersburg: Lan: Planet of Music.

7. Alekseev, B.K. & Myasoedov, A.N. Elementary music theory. Moscow: Muzyka.

8. Beishlag, A. (1978). Ornamentation in music: With a preface. General. ed., comment. and after. N. Kopchevsky; Per. with him. Z. Wiesel. Moscow: Muzyka.

9. Rusyaeva, I.A. (2023). Elementary theory of music. Oral exercises with melismas: educational manual. St. Petersburg: Lan: Planet of Music.

10. Astashev, D.A. & Myatieva, N.A. (2017). Informative codes of nonlinear adiastematic notation: “memory” and “freedom”. Vestnik of Academy of Choral Arts, 7. Moscow: Victor Popov Academy of Choral Arts.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

The subject of the study presented for publication in the journal "Man and Culture", as indicated in the title ("Jewelry in the musical-theoretical teaching of Giusto Dacci: a didactic standard"), is the didactic standard of improvisational reading of jewelry written out with abbreviations of musical notation in the musical-theoretical teaching of the Italian composer, theorist and music teacher maestro Giusto Dacci. The author does not pay attention to the preliminary formalization of the research program, which, however, slightly complicates the reading and verification of the content, due to compensation for this shortcoming by the clear logic of the structure of the presentation of the results obtained. The author devoted the introductory part of the article to the terminological clarification of the basic category of "decoration" for research in the historical and cultural context of the development of a special thesaurus in European music theory and musical didactics, which clarified both the subject of research (a certain didactic standard) and the object of research (an interdisciplinary field of theory, didactics and performance practice related to the reading of notated jewelry). At the same time, significantly reducing the total volume of the article, the author reveals the degree of study of the research topic and concludes the introduction by arguing its relevance by saying "that the theoretical standard of jewelry created by Giusto Dacci in the middle of the XIX century became one of those that was actively implemented in the educational programs of Italian schools and conservatories ...". The actual problem of the study, as follows from further comparisons of a wide body of specialized Russian and foreign didactic and theoretical works with the development of Giusto Dacci, is the insufficient attention of individual theorists to the standard developed in detail by the Italian maestro, which is important "for understanding the facets of possible performing freedom in deciphering jewelry in works taken from a particular time chronotope." In other words, in addition to the artistic, musical-theoretical and musical-didactic value of the presented article, the author focuses on some unjustified underestimation of Maestro Dacci's contribution to academic musical culture, which reduces the gap of scientific knowledge formed for this reason. Attention is drawn to the system of notes developed separately by the author, which reveals the depth of the author's analysis of sources. This part of the reference apparatus of the article significantly complements the main text. The author's final conclusions are well-reasoned and beyond doubt. Thus, the subject of the study is disclosed quite fully and comprehensively at a high theoretical level. The research methodology, as well as the program as a whole, has not been formalized by the author, but it is quite obvious that it is a well-thought-out complex of special (thematic selection of sources and their comparative analysis, analysis of completeness and didactic clarity of standards for reading jewelry) and general scientific methods (comparison, typology, generalization, interpretation). Separately, attention should be paid to the clear logic of the presentation of the research results, which reveals itself from the problematization of a special thesaurus of the topic in a historical and cultural context to the completeness of the presentation of the improvisational reading of decorations written out with abbreviations of musical notation in various didactic standards and an empirical example of a detailed decoding of Maestro Dacci's gruppetto, revealing the advantage of the standard of the Italian theorist (subject of research). The author argues the relevance of the chosen topic by the fact that "the theoretical standard of jewelry created by Giusto Dacci in the middle of the XIX century became one of those that has been actively implemented in the educational programs of Italian schools and conservatories ...", and from the general context of the work, the advantages of developing a maestro for methodological equipment of performance and music pedagogy today become quite obvious. The scientific novelty of the presented research, reflected in the final conclusions, the author's selection and a detailed analysis of the sources, is beyond doubt. The style is scientific. The structure of the article perfectly reflects the logic of presenting the results of scientific research. Individual blemishes (in some places there are no spaces before the square brackets of references in the text; one of the fragments of the author's statement ("... an extensive history of jewelry is presented, which on the one hand reveals their life in time,") may require attention in terms of correcting the punctuation of the introductory phrase: "on the one hand") can be corrected by at the discretion of the issuing editor of the journal without distorting the author's thought. The bibliography, combined with the notes, reflects the problem field of the study well, is designed taking into account the requirements of the editorial board of the journal and GOST. The appeal to the opponents is logical, correct and quite sufficient. Of course, the interest of the readership of the magazine "Man and Culture" in the article presented by the author is guaranteed.

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|