|

MAIN PAGE

> Back to contents

Man and Culture

Reference:

Kruglova E.

Historical portrait of the first prima donna of Baroque opera: Vittoria Archilei

// Man and Culture.

2023. № 4.

P. 129-140.

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8744.2023.4.43644 EDN: WGJVSK URL: https://en.nbpublish.com/library_read_article.php?id=43644

Historical portrait of the first prima donna of Baroque opera: Vittoria Archilei

Kruglova Elena

ORCID: 0000-0001-6565-2083

PhD in Art History

Professor, The State Musical Pedagogical Institute named after M. M. Ippolitov-Ivanov

109147, Russia, Moscow, 36 Marxistskaya str.

|

elenakruglowa@mail.ru

|

|

|

Other publications by this author

|

|

|

DOI: 10.25136/2409-8744.2023.4.43644

EDN: WGJVSK

Received:

26-07-2023

Published:

05-09-2023

Abstract:

The name of Vittoria Archilei has entered the history of vocal art as the first opera prima donna in a new style of singing for the turn of the XVI-XVII centuries. During her lifetime, the singer enjoyed great popularity. Outstanding composers G. Caccini, J. Peri, S. D'India, E. de’ Cavalieri, etc. they admired her skill, noting the extraordinary tenderness of the sound of her voice, combined with its bright virtuosity. Archilei performance was significantly different from other singers, her contemporaries. It is not by chance that J. Peri calls the prima donna the Euterpe of his time. The article presents a creative portrait of Vittoria Archilei, the first brilliant interpreter of monodic music, an outstanding singer who created a new method of singing women. The methodological basis of the work is the principle of historicism. The cultural and historical research method was used. The biographical reconstruction was made on the basis of source studies with reviews of the singer's contemporaries, letters, music-critical articles. In Russian musicology, this article is the first special publication dedicated to the creative path of Vittoria Archilei. This material will be useful for musicians, singers performing old music, for its stylistically correct interpretation, as well as in training courses on the history of vocal performance at vocal departments of music colleges and faculties of universities.

Keywords:

Vittoria Archilei, opera diva, virtuoso singing, vocal ornamentation, improvisation, vocal technique, baroque music, Giulio Caccini, Antonio Archilei, monodic music

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

The formation of a solo singer as an important figure in musical life began, according to the Roman aristocrat, art lover Vincenzo Giustiniani, in 1575 [1, p. 106-107]. Of course, this does not mean that solo singing with accompaniment at the end of the XVI century was something new. Even among the court artists throughout the Renaissance, the musician was often at the same time a poet-lutenist-singer. The only difference was that the Renaissance musician was not professionally trained in virtuoso singing compared to the famous performers-composers of the late XVI century, among whom we highlight Giulio Cesare Brancaccio, Giovanni Luca Conforto, Giulio Caccini, Vittoria Arkilei et al . The first performers of the new genre – opera, created by Florentine composers, were, first of all, the composers themselves. Beautiful voices, a special manner of pronouncing the text distinguished their virtuoso singing. A separate question arose in connection with the performance of female roles in operas. One of the cardinals, the guardian of morality, noted: "as it is impossible to enter the Tiber and not get your feet wet, so it is impossible for a woman to sing at the theater and not lose her chastity" [2, p. 14]. However, the ban imposed by Pope Sixtus V in 1558 on the performances of women on stage never had legal force in the diplomatic missions of Bologna, Ferrara, and was also sometimes disapproved of in Rome [3, p. 37]. The singing career of women gained rapid development in Italy at the turn of the XVI-XVII centuries. In 1580, Alfonso II, Duke of Ferrara, created a women's ensemble called "Consort dames" ("Concerto delle donne"), distinguished by the special performing virtuosity of its participants. These ladies were lovers of vocal art, since they had not received professional musical education since childhood, which was necessary for a subsequent musical career. And despite this, they demonstrated to the audience not only the beauty of their voices, but also a fairly developed ornamental art [4, p. 122]. In the period from 1580-1590, this practice was adopted by other Italian courts, and female instrumentalists were often added to ensembles. V. Giustiniani in his "Discourses on the Music of Our Time" quite interestingly described the art of music-making ladies from the court circles of Mantua, Ferrara and Rome, who competed not only with vocal staging of voices, but also with coloratura with elegant passages [5, pp. 118-119]. In the first operas at the turn of the XVI-XVII centuries, the singers acquire the status of highly paid participants in productions. At this significant time in Rome – the center of highly developed coloratura singing – many professional soloists are being formed. One of them was the famous Vittoria Concarini Arquilei. The brightest Roman singer, a sought-after performer, she entered the history of music and vocal art as the first recognized master of a new style of figurative virtuoso style and, according to Giustiniani, created "a true method of singing for women" [6, p. 17]. The art and creative path of the first opera prima donna Vittoria Arkilea is mentioned in foreign musicology [7, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10], however, probably due to the stinginess and disunity of data about the singer, up to now there are no in-depth studies devoted to understanding her role in the history of culture. In the works of Russian musicologists, the artist's name is mentioned in an overview, often just for reference and fragmentary [11, 12, 13, 2]. This work is entirely dedicated to the first Baroque opera prima donna Vittoria Arikilei. Vittoria (nee Concarini) was born in Rome, which explains her pseudonym "Roman" ("La Romanina"). The exact dates of the singer's life are not known and according to different sources they differ, determining the time of birth between 1550-1560 and death – between 1620-1625. Only brief biographical information about the years of her life has been preserved. Unfortunately, there is no data on Vittoria's musical education in childhood. Her marriage, which took place in September 1578, most likely had a significant impact on her professional development. Vittoria's spouse was the famous composer, singer and lutenist Antonio Arquilei, who served for many years under Cardinal Alessandro Sforza, the future Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando de’ The Medici. Antonio was her teacher. In marriage, the couple had five children: two sons and three daughters. For most of her life, the singer and her husband served with the Duke, first in Rome and then in Florence. Arquilea's creative activity in Rome is not exactly documented. However, her high position emphasizes the fact of participation in a number of magnificent celebrations held in honor of ducal weddings. In 1584 Vittoria came to Florence to perform in musical court celebrations on the occasion of the wedding of Eleanor de' Medici and Crown Prince of Mantua Vincenzo Gonzaga. The diplomatic ambassador in Florence, Simone Fortuna, in a letter from Francesco Maria II della Rovere, Duke of Urbino dated April 21, 1584, describing the wedding entertainment, notes "Vittoria, who came from Rome, and other famous musicians" [14, p. 263]. Three years later, in 1587, the Arquilei couple at the invitation of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando de’ The Medici finally move from Rome to Florence. There Vittoria's collaboration with the influential composer Emilio de’ Cavalieri begins; soon she becomes his prot?g?. The singer was distinguished by her delicate impeccable taste and rare musicality, which were repeatedly emphasized by musicians, her contemporaries. She was immaculately proficient not only in vocal technique, including virtuoso improvisation, but also in artistic expressiveness techniques, with the help of which she achieved a wide variety of intonation colors and shades, which was previously unknown to singers. Giulio Caccini's school contributed to this in many ways. As his student, she received the secrets of a new style of singing, according to Caccini, "a noble manner of singing." "Signora Ippolita,– wrote Caccini, "Signora Vittoria [Arquilei] and Melchior [Palantrotti], bass, all three belong to my school, sing solo, in duets and trios" [15].

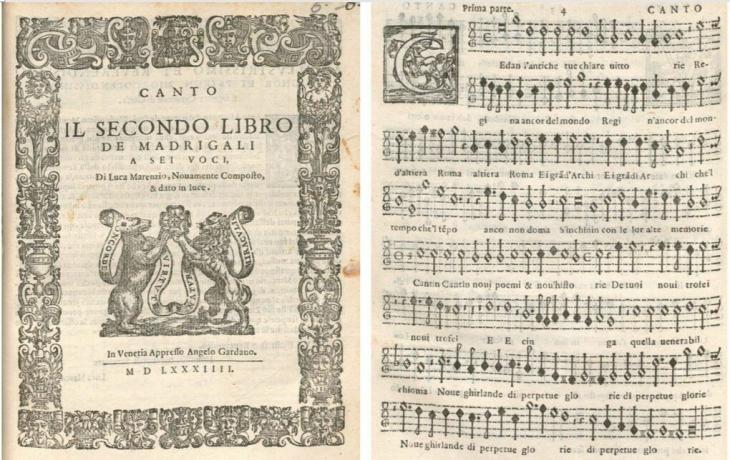

The affectionate, charming timbre of the singer's voice, the sincerity of the performance and excellent diction conquered the listeners. Often improvising, she delighted them, won the sympathy and great respect not only of her admirers, but also of the composers themselves, among whom were Jacopo Peri, Giulio Caccini, Sigismondo d'India, etc. Thus, India in her collection "Primo Libro de musiche da Canter solo" praises the gentle sound of Arquilea's sweet voice, and also speaks of her high intelligence shown in the singer's interpretations, noting the artist "above all other outstanding singers" [16]. Vittoria was greatly appreciated by Jacopo Peri. In the introduction to Eurydice, he writes: "Signora Vittoria Arquilei has always considered my music worthy of her performance, decorating it, but not from those groups, but from those long turns of voice, simple or double, which, thanks to her wit, are performed at any moment, in accordance with the customs of our time, which is the beauty of our singing, but especially with such graceful and graceful turns that cannot be learned from notes" [17, p. 5]. Presumably, the singer was not ignored by the most authoritative composer, singer Luca Marenzio, whose patrons were Prince Virginio Orsini, Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini Passeri and Pope Clement VIII. In 1584, in the second book of madrigals for six voices, Marenzio published the madrigal "Cedan l'antiche tue chiare vittorie", in which he sang the art of Vittoria Arquilea. Cedan l'antiche tue chiare vittorie (I concede to your early clean victories) Regina ancor del mondo, altiera Roma (Queen of Peace, Superior Rome) E i grand'archi che ’l tepo anco non doma (And the great Arches, not pacified by time) S’inchinin con le lor alte memorie. (Let us bow with venerable memory). Cantin novi poemi e nov'historie (Let's sing a new poem and a new story) De’ tuoi novi trofei (To your new achievements) E cinga quella venerabil chioma (And carried by this venerable head) Nove ghirlande di perpetue glorie. (Nine wreaths of Eternal Glory). Of course, it is not easy to agree with this, since there is no direct addressee in the text of Marenzio's madrigal. Italian musicologist Marco Bidzarini questions the dedication of these lines to Vittoria Arikilea. The researcher notes that the mention ("Archi") in the third line is not enough to accurately identify the singer ("Archilei"), and such a solemn nature of the poem suggests that it is addressed to a certain Roman influential lady [7, p. 102]. And yet, Vittoria Arquilei had a very high status and authority. At that time she was the prima donna of the Florentine court. Consequently, the dedication of Marenzio, with a share of probability, can be considered directed to the singer. Fig.1.  Fig. 1. The title page of the manuscript of the second book of madrigals for six voices by Luca Marenzio and a fragment of the madrigal "Cedan l'antiche tue chiare vittorie", 1584. Fig. 1. Title page of the manuscript of the second book of madrigals for six voices by Luca Marenzio and a fragment of the madrigal "Cedan l'antiche tue chiare vittorie", 1584. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Munich). Being at the height of fame, in 1589 Vittoria and her husband participated in the staging of a grand spectacle – the comedy "The Pilgrim" ("La Pellegrina") in honor of the wedding celebrations of Grand Duke Ferdinand with Christina of Lorraine, the granddaughter of Catherine de' Medici. The six musical interludes that make up The Pilgrim were written by outstanding composers of that time: Cristofano Malvezzi, Antonio Arquilei, Luca Marenzio, Giulio Caccini, Giovanni de' Bardi, Jacopo Peri and Emilio de' Cavalieri. The theatrical performance opened with a spectacular picture: prima donna Vittoria Arquilea performed the main part, personifying the image of Harmony (Armonia Doria). Fig. 2.  Fig.2. Harmony of spheres. (Facade of the scene from the first intermezzo, 1589). An engraving by Agostino Carracci commissioned by the artist Bernardo Buontalenti (1590). Victoria and Albert Museum (London).

Fig. 2. Harmony of spheres. (Facade of the scene from the first intermezzo, 1589). Engraving by Agostino Carracci commissioned by the artist Bernardo Buontalenti (1590). Victoria and Albert Museum (London). Slowly descending on a cloud and playing a large lute, she performed the madrigal "Dalle pi? alti sfere" ("From the highest spheres"). Her singing was replete with ornaments and extensive passages, vividly demonstrating the splendor of virtuoso art. The true authorship of the madrigal has not been established, in various sources it is attributed to both Cavalieri and the wife of the singer Antonio. For example, in their research, Richard Taruskin, Yulia Litvinova attribute the authorship of the madrigal "Dalle sfere" to Cavalieri [18, 11]; Kevin Mason, Otto Kinkelday talk about the authorship of Antonio Arquilea [19, 20]; meanwhile, Marco Bidzarini, Anthony M. Cummings [7, 21] do not establish the exact authorship and indicate two composers in the works at the same time. German traveler Barthold von Gadenstedt, describing the nature of Vittoria's performance, noted that "she [Harmony] began to sing so sweetly, simultaneously "beating" on the lute, so that everyone talked about the impossibility of a human voice being so beautiful ..." [10, p. 56]. In the same "Pilgrim", but already in the sea interlude No. 5, Vittoria embodied the role of Amphitrite – the sea queen, the wife of Poseidon, according to Homer – the goddess of waves, personifying the movement of the sea. Madrigal "Io che l'onde raffreno" ("I who hold back the waves") composer Luca Marenzio, performed by the singer, made an equally vivid impression on the audience. This is evidenced by Simone Cavallino: "In the blink of an eye, [the scene] turned into a stormy sea [with] solid rocks and waves that seemed so natural that everyone was amazed when looking at them, because they formed the foam that they used to [see] in the real sea. In the middle of the aforementioned waves, a very beautiful siren appeared – with nine of her captives – with such sweet singing that it would not be surprising if it lulled and softened every cruel heart; then, after singing for a long time, she disappeared" [10, p. 42]. It is no coincidence that such reviews are seen in which there is no mention of virtuoso coloratura. On the contrary, the authors cite a comparison with the sweet singing of sirens, the gentle sound of the singer's voice. This confirms the technical perfection of Vittoria, the flexibility and flight of her voice, the softness of timbre and the presence of a wide palette of intonation colors with, of course, a confident mastery of singing breathing, without which neither virtuoso fluency nor the embodiment of various shades of feelings are possible. The singer was famous for her ingenuity, combining bright virtuosity with a "beautiful dramatic manner of singing" (R. Rolland). And if in the madrigal of Harmony from the comedy "Pilgrims", according to the preserved ornamental version (a fragment of the original ornaments of Vittoria Arquilea is presented in the book by A. Beishlag [22]), the singer abundantly used an almost incessant passage-melismatic technique, then in the madrigal of Amphitrite, in the same comedy, the version with the introduction of complex fioritures seems quite difficult. It can be assumed that the madrigal of Amphitrite was just the material where the singer was able to show all her talent: to excite listeners by simple means. Perhaps, to convey the image, she not only performed charming coloratura roulades, but also used such techniques as sprezzatura (noble negligence – according to Caccini), e sclamazione (milling sound from forte to piano), invented by Caccini "to express feelings" [23]. At the beginning of 1590 in Rome, Vittoria and Antonio Arquilei were in the service of the Grand Duke Ferdinando. At the turn of 1590-1591, the singer shone in Cavalieri's pastoral "Despair of Fileno" ("La Disperazione di Fileno"), causing tears from the audience with her wonderful singing [24, p. 242]. According to the practice of that time, the prima donna performed madrigals in between participating in theatrical productions, performing at private events and in church. Being at the height of fame, Vittoria in 1598 sings in the opera "Daphne" by Jacopo Peri. It should be noted that the prima donna was the only woman among the performers, which confirms the participation of the singers in the first operas. Two years later, in 1600, she played the main role in his "Eurydice", staged on the occasion of the wedding of Marie de' Medici with Henry IV of France. The high status of Vittoria Arquilea as a professional female singer is emphasized by the lists of court payslips in the period from 1610-1642. (for thirty-two years!), in which her name was included along with other musicians. As Jane Bowers writes: "Although Vittoria's salary was somewhat lower compared to the female consort singers in Ferrara, in 1603 she received ten scudi a month, while her husband Antonio received eleven scudi; in addition, they were paid four scudi a month from the Grand Duke's own purse, so their total income was 300 scudi per year" [4, p. 122]. It is important to clarify here that at the same time, singers in Ferrarese were appointed only as ladies-in-waiting. Admiring the special art of Vittoria's virtuoso singing, Jacopo Peri calls her "The Euterpe of our century" [17, p. 5]. Recall, according to mythology, Euterpe is the ancient Greek muse of lyrical poetry and music, one of the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne. In the preface to Eurydice, J. Caccini characterizes Vittoria as an excellent singer, a long-time supporter of his new style [25].

Vittoria was short, elegant, however, not very beautiful, but modest and with high morals [2, p. 14-15]. Naturally multi-talented, she gained fame not only as a singer, lutenist, dancer, but also as a composer. This set her apart from other female performers. A fully recognized professional singer, Arquilei composed songs for her own performance, while the music-playing ladies of Ferrara did not have the skill of composition. Vittoria Arquilei, highly appreciated by her contemporaries, carried the reputation of a great interpreter of monodic music. The artistic intonation of the artist conveyed the whole range of feelings of the heroines embodied by her. In 1608, Marco de Galliano wrote about her as an excellent singer in terms of voice quality. In the Medici Palace in 1611 she performed in "La mascherata di ninfe di Senna" ("The Masquerade of the Nymphs of Senna"), presenting her own compositions to the audience; toured as a professional soloist and ensemble player in Italy, France. Often Vittoria's partners were the daughters of J. Caccini – Francesca and Settimia. Arkilei shunned competition with young performers. So, two years later, the Neapolitan virtuoso singer, contralto Adriana Basile, was enthusiastically received in Florence, after listening to which Vittoria no longer dared to sing next to her. The last mention of Arquilea's work is found in a review by the poet Jacopo Cicognini (1612) for a performance during the carnival season in Florence, where soloists performed their own madrigals: "The first one was performed by the Roman Vittoria Arquilea, with her inherent grace and angelic voice..." [6, p. 33]. The exact date of the prima donna's death is unknown. In 1614, the outstanding Italian poet Giambattista Marino in the third part of his collection "Lyra" ("La Lira") published a sonnet with the title "The Death of Vittoria, the famous singer" ("In morte di Vittoria, cantatrice famosa"). Some confusion in determining the date of the singer's death is caused by the publication of Marino's collection with the same sonnet in subsequent years (1629, 1646), as well as an obituary that Giustiniani wrote in 1628 [1, p. 137]. Meanwhile, according to Professor Isabel Emerson, the last record of Arquilea recorded in the Medici accounting books dates back to 1642 [8, p. 19]. The name of diva Arquilea, as well as her achievements in the development of Baroque music, remain in oblivion to this day. The analysis of the artist's creative path emphasizes her high status and social position. Vittoria Arquilei was able to make a long career and achieve a reputation as one of the best singers in Italy. She is the first professional opera singer in the history of vocal art, as R. Rolland described her as "the first singer of the era" [9, p. 82]. Masterfully mastering a new style of singing, Vittoria Arquilei skillfully combined brilliant virtuosity appropriate to the meaning of the text with new, previously unknown means of expression, called J. Caccini "effects" used in performance for the greatest expressiveness. A great interpreter of monodic music, the first opera prima donna Vittoria Arquilei played a key role in the development of the Baroque musical style and in particular the Baroque vocal tradition.

References

1. Solerti, A. (1903). Le origini del melodramma: testimonian ze dei contemporanei. [The origins of melodrama: testimonial ze of contemporaries.]. Torino: Fratelli Bocca.

2. Yaroslavtseva, L. K. (2004). Opera. Singers. Vocal schools of Italy, France, Germany of the XVII-XX centuries. Moscow: Golden Fleece Publishing House.

3. Celletti, R. (2000). La grana della voce. Opere, direttori e cantanti. [The grain of the voice. Operas, conductors and singers]. Milano: Baldini & Castoldi.

4. Bowers, Ja. & Tick, Ju. (Eds.). (1986). Women making music: The Western art tradition, 1150-1950. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

5. Shestakov, V. P. (2007). Philosophy and culture of the Renaissance. The Dawn of Europe. St. Petersburg: Nestor-History.

6. Cook, S. C. (1984). Virtuose in Italy, 1600-1640: a reference guide. New York: Garland.

7. Bizzarini, M. (2003). Luca Marenzio: The Career of a Musician Between the Renaissance and the Counter-Reformation (J. Chater, Trans.). Routledge.

8. Emerson, I. (2005). Five centuries of women singers. Bloomsbury Academic.

9. Rolland, R. (1895). Les origines du théâtre lyrique moderne: histoire de l'opéra en Europe avant Lully et Scarlatti. [The origins of the modern lyric theater: history of opera in Europe before Lully and Scarlatti]. Paris: E. Thorin.

10. Treadwell, N. (2007). Music of the Gods: Solo Song and effetti meravigliosi in the Interludes for La pellegrina. Current Musicology, (83). doi.org/10.7916/cm.v0i83.5087

11. Litvinova, Yu. A. (2010). A. Interludes "da Principi": the seven rules of Giovanbattista Strozzi Jr. // Scientific Bulletin of the Moscow Conservatory, 2, 74-105.

12. Parin, A. V. (2019). Between Rome and Florence. The life and works of Emilio de’ Cavalieri = Between Rome and Florence. Life and Creations of Emilio de' Cavalieri // Music Academy: scientific-theoretical and critical-journalistic journal, 3, 62-73.

13. Simonova, E. R. (2006). Singing voice in Western culture: from early liturgical singing to bel canto (Unpublished doctoral dissertation thesis). Moscow State Conservatory named after P. I. Tchaikovsky. Moscow.

14. Kirkendale, W. (1993). The Court Musicians in Florence during the Principle of the Medici, With a Reconstruction of the Artistic Establishment. Florence: Leo S. Olschki.

15. Carter, T. (1983). A Florentine Wedding of 1608. Acta Musicologica, 55(1), 89–107. doi.org/10.2307/932663

16. D'India, S. (1609). Le musiche da cantar. [The music to sing]. Milan: l'herede di Simon Tini, & Filippo Lomazzo.

17. Peri, J. (1600). Le Musiche di Jacopo Peri nobil Fiorentino Sopra L'Euridice. [The Music Jacopo Peri nobil Fiorentino Above Eurydice]. Firenze: Giorgio Marescotti.

18. Taruskin, R. (2009). Oxford History of Western Music: 5-vol. Set: 5-vol. Set. Oxford University Press.

19. Mason, K. (2005). Per cantare e sonare: accompanying Italian lute song of the late sixteenth century. In A. Coelho, V. A. (Ed.),Performance on Lute, Guitar, and Vihuela: Historical Practice and Modern Interpretation (pp. 72-107). Cambridge University Press.

20. Kinkeldey, O. (1910). Orgel und Klavier in der Musik des 16. Jahrhunderts; ein beitrag zur geschichte der instrumentalmusik. [Organ and piano in the music of the 16th century; a contribution to the history of instrumental music]. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Hartel.

21. Cummings, A. M. (2023). Music in Golden-Age Florence, 1250–1750: From the Priorate of the Guilds to the End of the Medici Grand Duchy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

22. Beyschlag, A. (1908). Die Ornamentik der Musik. [The ornamentation of music]. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

23. Caccini, G. (2023). TheNew Music: textbook. (K. M. Mazurin, Trans.). In E. A. Sergeeva (Ed.). St. Petersburg: Planet of Music. Retrieved from https://e.lanbook.com/book/307481. Access mode: for authorization. users. (Original work published 1602).

24. Pirrotta, N., Elena Povoledo (1982). Music and theatre from Poliziano to Monteverdi. Cambridge University Press.

25. Caccini, G. (1609). L'Evridice composta in mvsica In Stile Rappresentatiuo da detto Romano. [The Eurydice composed in music In the Style Represented by said Roman]. Firenze: Giorgio Marescotti.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

The subject of the article "Historical portrait of the first opera prima donna of the Baroque era: Vittoria Arquilea" is the personality and work of singer Vittoria Arquilea. The relevance of the article is quite high, because, as the author himself writes, "the art and creative path of the first opera prima donna Vittoria Arquilea is mentioned in foreign musicology, however, probably due to the stinginess and disunity of data about the singer, there are no in-depth studies devoted to understanding her role in the history of culture until now. In the works of Russian musicologists, the artist's name is mentioned in an overview, often just for reference and fragmentary ..." This study is designed to fill this gap, and the researcher has achieved his goal. The article has an undoubted scientific novelty and meets all the criteria of a genuine scientific work. The author's methodology is very diverse and includes an analysis of a wide range of different sources, including many foreign ones. The author skillfully uses comparative historical, descriptive, analytical, etc. methods in all their diversity. The study, as we have already noted, is distinguished by its obvious scientific presentation, content, thoroughness, and clear structure. The author's style is characterized by originality, imagery, logic and accessibility. Let's focus on the positive aspects of this study. The introduction characterizes in detail the "singing career of women", then the author describes in detail the work of Vittoria Arquilea, demonstrating a deep study of many sources, thanks to which the work is characterized by special depth and reliability. Thanks to the work of the researcher, the creative portrait of the singer appears before the reader: "The singer was distinguished by her delicate impeccable taste and rare musicality, which were repeatedly emphasized by musicians, her contemporaries. She was immaculately proficient not only in vocal technique, including virtuoso improvisation, but also in artistic expression techniques, with which she achieved a wide variety of intonation colors and shades, which was previously unknown to singers." Or: "The gentle, charming timbre of the singer's voice, the sincerity of her performance and excellent diction captivated the audience. Often improvising, she delighted them, won the sympathy and great respect not only of her admirers, but also of the composers themselves, among whom were Jacopo Peri, Giulio Caccini, Sigismondo d'India and others." Here is another example of the researcher's accurate analysis: "It is no coincidence that such reviews are seen in which there is no mention of virtuoso coloratura. On the contrary, the authors cite a comparison with the sweet singing of sirens, the gentle sound of the singer's voice. This confirms Vittoria's technical perfection, the flexibility and flight of her voice, the softness of timbre and the presence of a wide palette of intonation colors with, of course, a confident mastery of singing breathing, without which neither virtuoso fluency nor the embodiment of various shades of feelings are possible. The singer was famous for her inventiveness, combining bright virtuosity with "a wonderful dramatic manner of singing" (R. Rolland)." The author thoroughly studied the sources, comparing them, which had a positive effect on the quality of the study: "Slowly descending on a cloud and playing a large lute, she performed the madrigal "Dalle pi? alti sfere" ("From the highest spheres"). Her singing was replete with ornaments and extensive passages, vividly demonstrating the splendor of virtuoso art. The true authorship of the madrigal has not been established, in various sources it is attributed to both Cavalieri and the wife of the singer Antonio. For example, in their research, Richard Taruskin, Julia Litvinova attribute the authorship of the madrigal "Dalle sfere" to Cavalieri [18, 11]; Kevin Mason, Otto Kinkelday talk about the authorship of Antonio Arquilea [19, 20]; meanwhile, Marco Bidzarini, Anthony M. Cummings [7, 21] do not establish the exact authorship and they indicate two composers in the works at the same time." Analyzing the sources, the author builds a number of hypotheses and draws many correct conclusions: "One can assume that the madrigal of Amphitrite was just the material where the singer was able to show all her talent: to excite listeners by simple means. Perhaps, to convey the image, she not only performed charming coloratura roulades, but also used such techniques as sprezzatura (noble negligence – according to Caccini), esclamazione (milling sound from forte to piano), invented by Caccini "to express feeling." It is highly commendable that the author included drawings in the work: Fig. 1. The title page of the manuscript of the second book of madrigals for six voices by Luca Marenzio and a fragment of the madrigal "Cedan l'antiche tue chiare vittorie", 1584.and Fig.2. Harmony of the spheres. (Facade of the scene from the first intermezzo, 1589). An engraving by Agostino Carracci commissioned by the artist Bernardo Buontalenti (1590). The bibliography of this study is sufficient and very versatile, includes many different sources on the topic, including a number of foreign ones, and is made in accordance with GOST standards. The appeal to the opponents is presented to a wide extent, performed at a creative and highly scientific level. At the end of the study, the author also draws deep conclusions: "The name of prima donna Arquilea, as well as her achievements in the development of Baroque music, remain in oblivion to this day. The analysis of the artist's creative path highlights her high status and social position. Vittoria Arquilei was able to make a long career and achieve a reputation as one of the best singers in Italy. She is the first professional opera singer in the history of vocal art, as R. Rolland described her as "the first singer of the era" [9, p. 82]. Masterfully mastering a new style of singing, Vittoria Arquilei skillfully combined brilliant virtuosity appropriate to the meaning of the text with new, previously unknown means of expression, called J. Caccini "effects" used in performance for the greatest expressiveness. A great interpreter of monodic music, the first opera prima donna Vittoria Arquilei played a key role in the development of the Baroque musical style and in particular the Baroque vocal tradition." This research is of great interest to different segments of the audience – both specialized, focused on the professional study of music (musicologists, students, teachers, practicing musicians, etc.), and for all those who are interested in foreign art, including music.

Link to this article

You can simply select and copy link from below text field.

|

|